Abstract

American history teachers praise the educational value of Billy Joel’s 1980s song ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’. His song is a homage to the 40 years of historical headlines since his birth in 1949.

Which of Joel’s headlines will be considered the most important a millennium from now?

This column discusses five of the most important, and tries to make the case that three of them will become irrelevant, while one will be remembered for as long as the human race exists (one is uncertain). The five contenders are:

The Bomb

The Pill

African Colonies

Television

Moonshot

Article

My previous column concentrated on the Hall Weather Machine[1], with a fairly technocentric focus. In contrast, this column is not technical at all, but considers the premise that if we don’t know our past, then we don’t know what our future will be.

American history teachers praise Billy Joel’s 1980s song ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’ for its educational value. His song is a homage to the 40-years of historical headlines since his birth in 1949. Before reading further, go to http://yeli.us/Flash/Fire.html to hear it and to see the photographs that go with each phrase of the song.

Which of Joel’s headlines do you think will be most important, when considered by people a millennium from now? A thousand years is a long time.

Many of the popular figures Joel mentions from politics, entertainment, and sports have already begun to fade from living memory, so they are easy to dismiss. Similarly, which nation won which war will be remembered only by historians, though the genetic components of descendants affected by those wars will reverberate through the centuries. An interesting exercise would consider the most significant events of the eleventh century. English-speaking historians might mention the Battle of Hastings, but is Britain even a world power any longer? Where are the Byzantine, Ottoman, Toltec, and Holy Roman empires of a thousand years ago?

Note that there may be a difference between what most people 1,000 years from now will consider to be the most important and what may actually be the most important. In this case, just because the empires mentioned above are gone doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t have a significant role in creating our present and our future — we may simply be unconscious of their effect.

I will consider a few possibilities before arguing for one headline that is certain to be remembered, rightfully so, ten thousand years from now — if not longer.

The Bomb

First, most thoughtful people would include the hydrogen-bomb. A few decades ago, almost everyone would have agreed wholeheartedly. At that time, the policy of Mutual Assured Destruction hung heavily over every life in the USSR and the United States (if not the world). With the USSR now gone, and Russia and USA not quite at each others throats, the danger from extinction via a full-out nuclear exchange may be lower. However, the danger of a nuclear attack that kills a few million people is actually more likely.

Up till now, for a nation to become a great power and thereby wield great influence, it needed the level of organization that depended on civilization. No matter how brutal their government or culture — such as Nazi Germany, Communist Soviet Union, or Ancient Rome — their organization depended on efficient education, competent administration, large-scale engineering, and the finer things in life — to motivate at least the elite. Even then, some of the benefit would trickle down as “a rising tide raises all boats”. Competent and educated slaves were a key to Roman Civilization, just as educated bureaucrats were essential to the Nazi and Soviet systems.

Now, however, we are getting into a situation in which atomic weapons give the edge to the stark-raving mad — anyone who is willing to use them. This situation could be most destructive to prosperous, open, humanistic, and civilized nations, because they may be less willing to give up their comfort and freedom to defend against this threat. It appears very likely that within a decade or less, any ragtag collection of pip-squeak lunatics will be able to level the greatest city on Earth, even if it is defended by the world’s strongest army. This is because the advances in nuclear enrichment technology (along with all technology) will make it easier for pip-squeak lunatics to acquire or manufacture nuclear bombs.

That being said, however, it is also true that really advanced technology — specifically privacy-invasive information technology, perhaps in the form of throwaway supercomputers in a massive network of dustcams — might stop the pip-squeak lunatics before they can build and deploy their nuclear bombs.

In addition, another decade of technological development will result in nanobots. By the way, this isn’t just my prediction (the defense of which is a subject of a future column), but also the opinion of inventive dreamers such as Raymond Kurzweil, and of conservative achievers such as Lockheed executives. The development of nanobots means that cellular repair of radiation damage may also become possible (though the problems of controlling trillions of nanobots and of how to detect and repair radiation damage are additional separate and very difficult engineering and biological issues). Michael Flynn examined some of the nuclear strategic issues of this nanotech application in his short story “Washer at the Ford”.[2]

The problem is that there may be a five year window during which our only defense against nuclear-bomb-wielding pip-squeak lunatics will be privacy-invasive information technology, run by the FBI, NSA, and CIA, and their counterparts around the world. Yes, you should be worried, but probably not for the reasons you may think. The danger is not as much that these government agencies may infringe on your rights, but that the very nature of their jobs means that they won’t be able to apply Kranstowitz’s weapon of openness[3] against those who want us dead. To make matters worse, the U.S. intelligence agencies will likely follow the complex laws[3] that protect the privacy of U.S. persons[4] — to the exclusion of catching the nuclear lunatics. This is one reason that FBI, NSA, and CIA directors get new gray hairs every night.

Another problem is that the pip-squeak lunatics will also be able to buy cheap, privacy-invasive information (and other) technologies. Petro-dollars, peasant-made knickknacks, and mining rights have given ethically-challenged individuals in third-world countries astonishing wealth. Many of the world’s richest men live in the world’s poorer countries.[5] They have also learned cruel and clever means by which to keep their peasants down. The question is whether or not they can run the expensive technology they bought with their wealth and power. Buying cheap technology is one thing, but controlling it requires skilled people, and skilled people are more difficult to control. Can the dictators keep a small cadre of trusty elites to run the technology? North Korea and Iran are interesting (and rather scary) test cases at the moment.

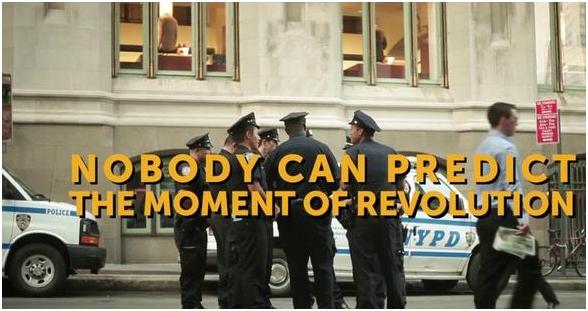

Another wild card is that while some dictatorships have become more totalitarian, there comes a point at which the downtrodden peasants (and students, and factory workers, and shopkeepers) don’t have anything to lose but their miserable lives. Meanwhile, totalitarian governments can’t keep up with technology as quickly as free ones can. This is when the system collapses of its own weight, and that is what happened to the USSR. The cell phone, Facebook, and Twitter-fed revolutions in Egypt, Libya, Syria, and elsewhere also seem to prove this point. Thus far, the Chinese leaders have been smart enough to adapt their economy without adapting their government. The jury is still out as to what will happen to them next (it may not be pretty for us if it ends badly, and there are many ways it can end badly).

Another wild card to consider is that most of the existing nuclear warheads are in the United States, Russia, and China. Americans conveniently forget, but non-Americans are very aware that the United States is (thus far) the only nation that has actually used an atomic bomb to kill people. On the other hand, America doesn’t have highly corrupt officials in charge of our nuclear arsenal (Pakistan), nor is it controlled by a near-dictator (Russia), nor by a totalitarian crazed nut-job (North Korea). In addition, a number of important Japanese leaders have publicly said that that controversial decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki was the correct one–“It could not be helped.“[6] A similar case might be made for Israel, which is surrounded by overwhelming numbers of Arab nations. Given the tensions in the area, a preemptive strike by Israel seems possible, if not likely. The important question then becomes: Under what grounds, if any, could such usage be justified? Of course, Iranian and other Arab leaders have often called for the total destruction of Israel, and eventually one of them may be willing to try it. On what grounds could they be justified?

Another issue is that once we lose New York or some other major city, Americans will accept any solution — including a totalitarian police state. So will the people of other democratic republics if they lose a major city to nuclear terrorists. But the solution is not necessarily a police state. David Brin has answered the “who guards the guardians” question with a clever answer: “We all do.” Over-simplified, his solution is to kiss most of your privacy goodbye. Either that or kiss your life, your liberty, and property, and your privacy all goodbye. Brin proposes that we should all submit to being on camera most of the time — as long as the camera essentially points both ways so we know who is watching us — i.e. the police, our neighbors, the pervert three blocks away, and our governments will know that we are watching them too. We must all shoulder the responsibility of policing our neighborhoods and our governments. The world will be like big village in which everyone knows everyone else’s business, but it’s OK because we are all accountable for our actions. Given the fact that human beings only behave when held accountable, it is the only real solution.[7]

Some may think it naive to expect that governments would ever allow their citizens to observe them in return for their observing us. On the other hand, between the increasing calls for government transparency, and the fact that even the chief of the IMF can be taken down by an lowly maid (with the help of the rule of law), there is hope. Not only that, but many of us have already given away much of our privacy on Facebook and YouTube. Don’t worry about it. Maybe I’m still a wide-eyed optimist, but look at the fall of the USSR empire. Nobody with two brain cells to rub together could have possibly predicted that it could have been so bloodless.

DARPA will certainly look for technological answers for nuclear bomb-related problems such as the nightmare of screening shipping containers. They will probably find some solutions, but during the critical transition phase towards productive nanosystems, will they be able to make those solutions affordable?

One nanotech solution to stopping nuclear bombs that are hidden in shipping containers is to stop all physical shipping altogether and just trade files over the internet, printing whatever you want on our desktops (BTW, you can build a very large printer in two steps). Our only problem then would be keeping our computer virus detectors up to date so that we don’t print something nasty.

To summarize, if anybody is around 1,000 years from now, then the nuclear bomb will not be considered an important issue.

The Pill

The second historically consequential development in the past 50 years that many people will propose as significant is the contraceptive pill.

Some claim that the Pill is necessary because we have a population problem. When I was in college in the 1970’s, it was “proven” to me, with the aid of computer models, that overpopulation was going to be the reason we were going to have food riots in the United States by 1985. So naturally, I’m as skeptical about overpopulation as I am about the imminent rapture. Everyone probably agrees that overpopulation results when the population exceeds the sustainable carrying capacity of the environment. But what determines that capacity? Technology multiplies it while ignorance, injustice, and war decrease it. On Earth today, there is currently no correlation between standard of living and population density.[8]

That being said, in a closed system, unlimited human population growth could result in a situation worse than simple human extinction. Natural ecosystems have population boom/crash cycles all the time, but other species don’t have access to nuclear bombs and other devices that can obliterate habitats. The overpopulation disaster on Easter Island occurred with a primitive culture. It still has grass, but not much of an ecosystem. Imagine what could have happened with modern technology.

The Pill fundamentally changed the relationship of men and women, the place of children in a family and, on the macro level, population dynamics. The family is the basic building block of society and civilization, not only because it is an economic unit (you don’t pay your spouse to wash the dishes or take out the garbage), but more importantly, because the family critically shapes the next generation. Therefore, a large change in family structures will have far-reaching effects, at least in the “short run” of five to ten generations. However, to steal from Jerry Pournell and Larry Niven: “Think of it as evolution in action.“[9] The people who embrace contraception as a path to “the good life” will (evolutionarily speaking) remove their vote for influencing their future within a few generations. It is true that for humans, memes may carry as much weight as genes, but the same process applies — as long as meme propagation is kept below a critical level, perhaps by co-traveling xenophobic memes. On the other hand, people who don’t have much of their material resources tied up in children may have more time to devote to meme propagation. However, many studies have shown than the people who have the greatest impact on teens and pre-teens are their parents.[10]

One possible result is that a millennium from now, the Pill will be a small blip, as inconsequential as the Shakers, and for essentially similar reasons. Nanotechnology-enabled life extension techniques will extend that blip for a while, but because the prolific pro-natalists will continue having even more children for their longer lives, more pro-natalists will be born to outvote the anti-natalists. This is why the Jewish Knesset now has a significantly higher percentage of Ultra-Orthodox than when it began,[11] why Utah’s government is almost 100% Mormon,[12] and why the Amish are one of the fastest growing minority in the world, with an average of 6.8 children per family.[13]

The opposing trend is controlled by a number of factors. First, the birth rate goes down as women’s educations go up. This occurs partially because practically speaking, it is more difficult to go to school while being married and raising children. More subtly, however, it is because school is an investment in learning a professional trade — it is a different investment than children. In addition, women and men are implicitly and explicitly taught that a better career is more important than raising more children.

The problem isn’t that women are being educated. The problem is that if they are taught something that results in the extinction of our egalitarian, humanistic, and liberal society by one that is misogynistic, xenophobic, and unjust, then something is wrong.

One weapon of the contraceptive culture is the reeducation of the pro-natalist’s children. Proponents of secularization would call this “giving people free access to all information” not “reeducation”. But when Bibles are banned from the classroom, and students are taught in many ways that they are just animals, it seems like imposition of a secular viewpoint. At least they could teach the debate — and at the end of the semester, the students could try to guess the teacher’s bias (if they can’t, then the teacher presented both views with equal force).

There are more than a million home-schooled children in the U.S., up to two-thirds of whom are there primarily because their parents fear the imposition of our government’s ideas on their children.[14] This quiet protest is so feared by governments that parents are prosecuted for doing this, not only in all totalitarian countries but even in some democratic nations.[15] The alternative is that the governments of open, liberal, and secularized nations (that accept contraception) will decide that the vote of the increasing minority is wrong. Could their right to vote be taken away? Of course it can; it has happened before.

A pessimistic view of this possibility of disenfranchisement is also supported by the prevalence of abortion in liberal democracies. Given the accuracy of ultrasound imagery, if we can ignore the right to life for our most innocent and helpless, then how safe is something as meager as the right to vote? Niemöller’s poem about trade unionists, Communists, and Catholics comes to mind.[16] So do the events in ancient Egypt, during the three or four hundred years between the famines that Joseph ameliorated (Genesis 50:22). The Egyptian upper class used contraception[17], and they felt threatened by the increasing numerical growth of the Jews, who had strict injunctions against it.

Is it good for our country that more than a million children are being taught by their parents? What if rebellious parents are teaching strange and dangerous ideas? How do we decide which ideas are dangerous? Do we censor and suppress them? After all, ideas have consequences.

The answer is that there are limits to what parents can do, but very few — if any — on what they teach. The whole point about freedom of religion is that we can believe what we want, as long as we do not destroy society or individuals with our actions. Our constitution was written not to limit individuals, but to put strict limits on government, since it is inherently more powerful.

The temptation to avoid having children is not limited to any particular culture. The reason is simple: raising children is an expensive, risky, and difficult investment. Parents must be willing to give up fancy vacations, luxury cars, time to themselves, a good night’s sleep, stress on their marriage, and many other things, thus weighing against the pro-natalist agenda. However, the culture that teaches that children are a blessing and a worthwhile investment instead of a cost will overcome those that do not — even if it tends to encourage people to be ignorant, misogynist, racist, and illogical (like two polygamist religions that start with the letter “M“[18]).

Cyril M. Kornbluth’s 1951 short story “The Marching Morons” illustrates another potential downside to the anti/pro-natalist issue by portraying a scenario in which selective pressure resulted in smart people breeding themselves out of existence. It also, despite the derogatory title, provides a warning: the originator of the “Final Solution” (placing all the fertile morons onto one-way rockets to nowhere) ends up screaming futilely as he himself is loaded on one of the last rockets. Kornbluth’s main premise seems logical. People are often willing to trade children for the better material things and higher standard of living, and those with more education are more willing to do so. But is the resulting cost to society worth it?

What will happen when productive nanosystems and advanced software lowers the price of goods and services to very low levels? Many other things will happen at the same time, but in a society of economic abundance, the expense of children will drop significantly — and will be limited only by attention span and desire (and possibly expanded by reproductive-enhancing technologies including parthenogenesis and male pregnancy). Is there a gene for liking children? Or is it a meme that is culturally transmitted? Evolution favors both. Of course, evolution may also favor a “Boys from Brazil“[19] scenario (in which numerous clones of a dictator are grown to reinstate his rule). This strategy may be successful as long as the clones survive to adulthood and can reproduce.

While a contraceptive culture is non-sustainable, especially in the face of a competing culture whose population is growing, it must be noted that a pro-natalist culture is also non-sustainable. Isaac Asimov pointed out that even if we could overcome all technological obstacles, any growth rate will eventually result in humanity becoming a big ball of flesh, expanding at the speed of light (BOFESOL, or BOF for short). At a modest 3% rate, we will reach the initial BOF in only 3,584 years. After that, the speed of light will limit growth.

However, the fact that a contraceptive culture is non-sustainable in a significantly shorter term than the pro-natalist one is why it makes sense for governments to support traditional religions in their efforts to maintain traditional morality and fertility. The difficult problem is finding ways to ensure the survival of a culture without it becoming xenophobic. This is difficult to do when we think that we have Absolute Truth and the One True Religion on our side. But then exactly how do we know that our particular set and ordering of values is the objectively correct one? Note that the denial of the existence of any objectively maximum set of values exists is itself a particular set of values. And note also that sustainability and tolerance are also values that, like all values, must be assumed because they cannot be proven.

Given the contradictory evidence and shifting values, it is likely that equilibrium between pro-natalist and contraceptive meme sets can never be reached. Instead, humanity will likely experience benign (and sometimes not-so benign) boom and crash cycles similar to those that natural ecosystems suffer from. Only for us, our cycles will be constrained by opinions and technological capabilities, not by predators.

African Colonies

A third historical event that may be of consequence a thousand years from now is “Belgians in the Congo”. The Belgian regime in the Congo was about as brutal and inhuman as any the Europeans imposed on its colonies. However, the European Empires spread Christianity in Africa — where it remains a fast-growing religion. This African event may be as significant as when the Spanish and Portuguese spread Christianity in Latin America, and will bring about a fundamentally different world than if Africa had gone Islamic, Hindu, or Confucian. Think of Latin American worshiping the Aztec gods with human sacrifice, or the impact on us if it were an Islamic Civilization. We would live in a very different world.

Then again, Africa may still turn Islamic. After all, Islam generally values large families, just like the fast-growing Mormon and Amish religions do. On the other hand, when Muslims become secularized, they reduce the number of their offspring, just like secularized Christians do — hence their accompanying philosophies will suffer the same fate. The result will be that in order to survive in the long term, future generations must be hostile to secularization, and probably hostile to each other’s religious views also (not a pleasant thought, even if they do share many of the same values). Over the next thousand years, in view of the exponential increase in technological power, which viewpoint will win? The answer depends on science, theology, and demographics.

A handful of nominal Christians destroyed the Aztec civilization, not because of their technology (though that helped), but because the Aztec civilization was based on a great and powerful falsehood — that in order for the sun to rise every morning, human blood needed to be shed — thereby earning the hatred of the neighboring tribes whose blood it was that was usually shed. Islam is not as false as the Aztec religion — otherwise it would not have lasted this long. But the jury is still out on whether it can survive the extreme technological advancement that productive nanosystems will bring. Will fanatical Muslims be able to design and build the nanotech equivalent of 747 jets that they can fly into the skyscrapers of their enemies? Or will they just learn how to use it in unexpected and terrorizing ways? Given the high level of technological advancement in the Muslim empire a thousand years ago, the answer seems to be “yes” to both questions. However, Islam’s ultimate rejection of reason is its Achilles heel, and in the past it helped lead to the decline of the Ottoman Empire after its peak in the 1300s. This is because Islam’s idea of Allah’s absolute transcendence is incompatible with the idea that the universe is ordered and knowable. Psychologically, the problem is that if the universe is not ordered and knowable, then why bother learning and doing science? Meanwhile, Hinduism has many competing gods, and this leads (like in ordinary paganism) to its rejection of the logical principle of contradiction — without which science is impossible. Confucianism seems to be more a moral code than a religious one, so it seems that it could be accommodating to technology — but that didn’t seem to help its practitioners develop it before they collided with the West. Similarly with Buddhism. Meanwhile, the decadent West’s deconstructionism and nihilism is gnawing at its parent’s roots, rejecting reason and science as merely tools of power.

It can be claimed that religious views will keep changing and splitting into new orthodoxies. In that case, the result will be an ever-shifting field of populations and sub-populations with none winning out completely over the others. But as far as I can tell, neither Judaism, Catholicism, Buddhism, nor Islam have changed any of their core beliefs in the past few millennia. In contrast, the Mormons have changed a number of their major doctrines, and so have the Protestants. This does not bode well for their long-term survival as a coherent organization, though the Mormons do have their high fertility on their side.

At the moment, the whole world is copying the Christian-rooted West, as many of their scientific elite are educated in Europe and the United States. It is difficult to say to what extent they understand the philosophical underpinnings of science. When their own universities start to educate their elite, their cultural assumptions will probably displace the Judeo-Christian/Greek philosophy of the West. Then what? It depends if science, which is the foundation of technological superiority, is simply a cargo cult that works. My claim is that science will only continue working for more than a generation or two if its underlying assumptions come with it — that the universe is both ordered and knowable.

These Judeo-Christian assumptions are huge — though atheists, agnostics, and (maybe) Muslims and Buddhists should also be able to accept them. However, every scientist still faces the question of why the universe is ordered and knowable (and if you’re not constantly asking the next question, especially the “why” question, then you’re not a very good scientist). The theistic answer of design by creator[20] is not too far away from the assumption of an ordered and knowable universe, and from there, one begins skating very close to the concept that we are made “Imago Dei”–in God’s image. Some people think that there is too much hubris and ego to that belief, but you don’t see dolphins landing on the Moon, or chimpanzees creating great symphonies (or even bad rap).

“Imago Dei” is the most logical conclusion once we can explain why the universe is predictable and knowable. And being made in God’s image has other implications, especially in terms of our role in this universe. Most notably, it promotes the idea of human beings as powerful stewards of creation, as opposed to subservient subjects of Mother Nature, and it will pit Nietzschean Transhumanists and Traditional Catholics against Gaian environmentalists and National Park Rangers.

Television

Writing has been around for thousands of years, while the printing press has been around for almost 600. It would seem that the printing press was the one invention that, more than anything else, enabled the development of all subsequent inventions. Television could be considered an improvement over writing, and given that large amounts of video can be subject to slightly less interpretation than an equal amount of effort writing text, our descendants might get a better, more complete depiction of history than they could get from just text or physical artifacts. However, the television that Joel mentioned was controlled by the big three television networks. This was because the cost to entry was so high (currently from $200,000 to $13 million per episode). So the role of television of the 1960s was similar to the role of books in Medieval Europe, where the cost of a book was equivalent to the yearly salary of a well-educated person). For this reason, Joel’s headline will not be considered significant, though he was close.

He was close because television’s electronic video display offspring, the computer — especially when connected to form the Internet — will certainly be significant. It will be as significant as the nuclear bomb and the Pill combined, if and when Moore’s Law ushers in the Singularity. But Joel was writing a song, not engaging in future studies. We might as well criticize him for not mentioning the coining of the word “nanotechnology”.

Moonshot

A few of Billy Joel’s headlines may be remembered 1,000 years from now, but none mentioned so far will really be significant.

I would go out on a limb and say that other than the scientific and industrial revolutions, the American Constitution, and the virtual abolishment of slavery, little of consequence has happened in the last thousand years. There is, however, one significant event that happened in the 1400s. No, it’s not Spain kicking out the Muslims. It’s not even Admiral Zheng He, Admiral of China’s famed Dragon Fleet, sailing to Africa in the 1420s, though we’re getting warmer. As impressive as they were, Zheng’s voyages did not change the world. What did change the world was the tiny fleet of three ships that returned from the New World to Spain in 1492.

Apollo and Star Trek both pointed to the next and final frontier. It is true that little has happened in the American space program since Apollo, and with the retirement of the 1960s-designed Space Shuttle, even less is expected. This poor showing has occurred because the moon shot, as awe-inspiring as it was, was a political stunt funded for political reasons. The problem is that it didn’t pay for itself, and we therefore have a dismal space program. However, with communication, weather, and GPS satellites, we have a huge space industry. It’s all about the value added.

On the other hand, it’s the governmental space programs that seem to make the initial (and necessary) investments in the basic technology. More importantly, these programs give voice to that which makes us human — “to look at the stars and wonder”.[21]

Realistically, looking at the historical records of Jamestown and Salt Lake City, space development will occur when prosperous upper class families can sell their homes and businesses to buy a one-way ticket and homesteading tools. In today’s money, that would be about one or two million dollars. We have a long way to go to achieve that price break, though it helps that Moore’s Law is exponential.

There have only been a dozen men on the Moon so far, but Neil Armstrong will be remembered far longer than anyone else in this millennium. After the human race has spread throughout the solar system, and after it starts heading for the stars, everyone will remember who took the first small step. The importance of this step will become obvious after the Google Moon prize is won, and after Elon Musk and his imitators demonstrate conclusively that we are no longer in a zero sum game.

That is something to look forward to.

Tihamer Toth-Fejel is Research Engineer at Novii Systems.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Andrew Balet, Bill Bogen, Tim Wright, and Ted Reynolds for their significant contributions to this column.

Footnotes

1. Tihamer Toth-Fejel, The Politics and Ethics of the Hall Weather Machine, https://lifeboat.com/blog/2010/09/the-politics-and-ethics-of-the-hall-weather-machine and http://www.nanotech-now.com/columns/?article=486

2. Michael Flynn, Washer at the Ford, Analog, v109 #6 & 7, June & July 1989.

3. Arthur Kantrowitz, The Weapon of Openness, http://www.foresight.org/Updates/Background4.html

4. United States Signals Intelligence Directive 18, 27 July 1993, http://cryptome.org/nsa-ussid18.htm

5. e.g. Mexico, India, Saudia Arabia, and Russia http://www.forbes.com/lists/2010/10/billionaires-2010_The-Worlds-Billionaires_Rank.html Also, the petro-dollar millionaires in the Mideast http://www.aneki.com/millionaire_density.html

6. There is an interesting discussion at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debate_over_the_atomic_bombings_of_Hiroshima_and_Nagasaki

7. David Brin,The Transparent Society, Basic Books (1999). For a quick introduction, see The Transparent Society and Other Articles about Transparency and Privacy, http://www.davidbrin.com/transparent.htm.

8. Tihamer Toth-Fejel, Population Control, Molecular Nanotechnology, and the High Frontier, The Assembler, Volume 5, Number 1 & 2, 1997 http://www.islandone.org/MMSG/9701_05.html#_Toc394339700

9. Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle, Oath of Fealty. New York : Pocket Books, 1982

10. KIDS COUNT Indicator Brief, Reducing the Teen Birth Rate, July 2009. http://www.aecf.org/~/media/Pubs/Initiatives/KIDS%20COUNT/K/KIDSCOUNTIndicatorBriefReducingtheTeenBirthRa/Corrected%20teen%20birth%20brief.pdf

11. From a small group of just four members in the 1977 Knesset, they gradually increased their representation to 22 (out of 120) in 1999 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haredi_Judaism). The fertility rate for ultra-Orthodox mothers greatly exceeds that of the Israeli Jewish population at large, averaging 6.5 children per mother in the ultra-Orthodox community compared to 2.6 among Israeli Jews overall (http://www.forward.com/articles/7641/ ).

12. As of mid-2001, the Governor of Utah, and all of its Federal senators, representatives and members of the Supreme Court are all Mormon. http://www.religioustolerance.org/lds_hist1.htm

13. Julia A. Ericksen; Eugene P. Ericksen, John A. Hostetler, Gertrude E. Huntington. “Fertility Patterns and Trends among the Old Order Amish”. Population Studies (33): 255–76 (July 1979).

14. 1.1 Million Homeschooled Students in the United States in 2003. http://nces.ed.gov/nhes/homeschool/

15. HOMESCHOOLING: Prosecution is waged abroad; troubling trends abound in US http://www.bpnews.net/BPnews.asp?ID=34699

16. http://timpanogos.wordpress.com/2010/02/26/quote-of-the-moment-martin-niemoller-i-did-not-speak-out/

17. http://www.patentex.com/about_contraception/journey.php

18. I should note that almost all of the people I have personally known from these two religions are trustworthy, intelligent, and a pleasure to meet. Despite what they are taught in their sacred texts.

19. Ira Levin, Boys from Brazil, Dell (1977)

20. There are many question to follow. How did He do it? Why is He masculine? Why did He do it? How do we know? That last question is especially relevant.

21. Guy J. Consolmagno, Brother Astronomer: Adventures of a Vatican Scientist, McGraw-Hill (2001)