Before the Revolutionary war in North America, a movement in favor of establishing independence paved the way. Common Sense, written by the political activist and philosopher Thomas Paine, became a central part of it. In this paper I go over some of its points while making correlations with the movement for indefinite life extension.

The people of America’s 13 colonies weren’t in agreement on how to move forward with their disputes with Great Britain. Like Thomas Paine wrote, “The mind of the multitude is left at random, and seeing no fixed object before them, they pursue such as fancy or opinion starts.” Common Sense fixed the object of independence, rather than reconciliation with tyranny, in enough minds to help make it happen.

True freedom is about much more than things like the ability to sail the open seas or be independent from the authority of kings – it is about access to all constructive opportunities, of which there may be an infinite number, and to which there are still innumerable barriers. Every day asks us whether we want to put in work to break more of the barriers around us, and every day we either reconcile with the conventions of laissezfaire or continue the struggle for freedom.

Movements have broken many bonds over the decades and centuries. What was once a world overrun with crushing suppressions is now manageable and improving in many countries on numerous fronts. We need that “fixed object” that Paine was talking about so we can open the frontiers of industrialized peoples next most pressing freedom. That object is time, the walls of defined lifespans must come down. Nothing is more absolutely enslaving than <125 year death sentences for all, and the times are ripe and ready to take it on. The world works with and engineers biology in many ways now and gets better at it faster as the toolbox of biotechnology continues to deepen. Biological mastery is in the cards if we play them.

Paine wrote, ”O ye that love mankind! Ye that dare oppose, not only the tyranny, but the tyrant, stand forth! Every spot of the old world is overrun with oppression. Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia, and Africa, have long expelled her—Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.” In that style I would write, “O ye that love life! Ye that dare oppose, not only the symptoms of mortal afflictions, but the roots, stand forth! Every spot of the world is overrun with death. Life hath been hunted round the globe. Tradition and religion have long expelled her—politics regards her like a stranger, and trend setters have given her warning to depart. O! receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for this survivors blood that fights on through us.”

How many injustices should we accept? How much lack of freedom should we endure? ”There are injuries which nature cannot forgive; she would cease to be nature if she did. […] The robber, and the murderer, would often escape unpunished, did not the injuries which our tempers sustain, provoke us into justice.” I often say that anger for death is there for the same reason that pain is there when touching a hot stove — it is your body prompting you to take corrective measures to end the pain. We ought endure such misfortunes when we must and take action against them when we can.

The time for life extension is now because the tools and insights are here, and also because as Paine says, “When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember, that virtue is not hereditary.” You know that the people in your life deserve to live, you understand the importance of working to get this done now, but our grandchildren might not. Humanity cannot afford to pass the buck off into the darkness. I may believe that posterity will be roughly as virtuous as us, but I’m not a prophet. Dark times tend to sweep in on their own schedules.

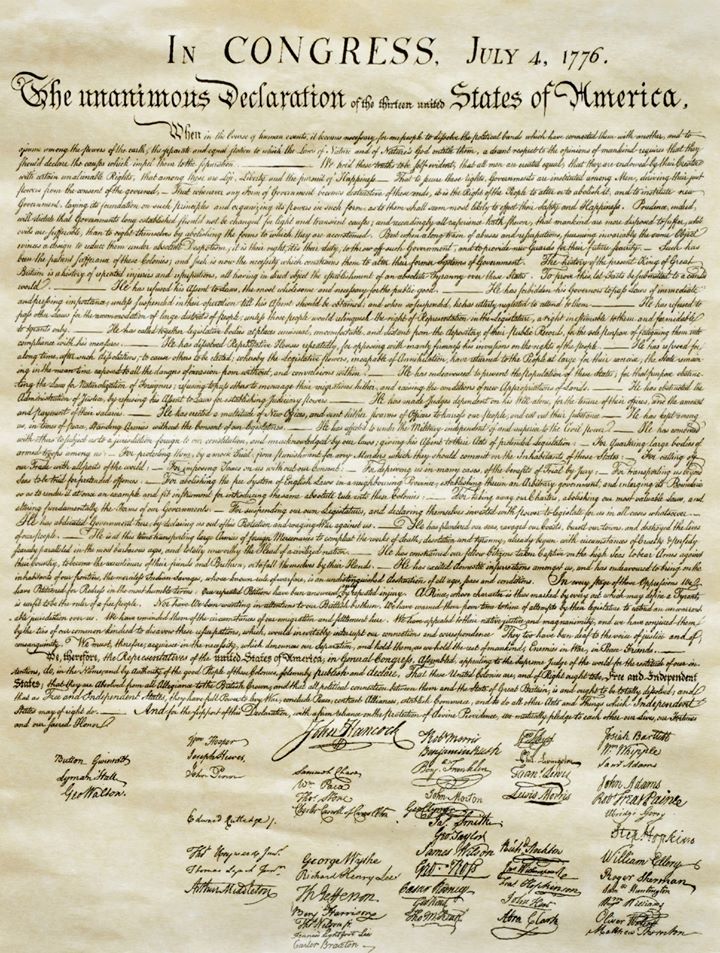

It is our duty to get this job done. “[N]othing can settle our affairs so expeditiously as an open and determined declaration for independance.” The Declaration of Independence was written after Common Sense, mainly by Thomas Jefferson. A life extension version of it might look something like this:

Declaration of Independence from Death

We hold this truth to be self-evident, that all people are created equal, that they are endowed by life with certain unalienable rights, that chief among them is life itself, that is, freedom from incurring the injustice of a defined lifespan. To secure this right, science is practiced among people, deriving its just power from the purest form of the pursuit for answers, for the lifting of the veils of ignorance that hold us back from true freedom. Whenever anything becomes destructive of this end, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new practices, laying its foundation on principles and organizing its power in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their survival. The history of death is a history of repeated horrors and atrocities. Let the facts be submitted to a candid world.

Every person who dies misses out on what very well may be an infinity of incredible wonders and opportunities. This is stiflingly enormous opportunity cost. People lose their freedom, memories, goals, thoughts, themselves; others lose them; all of humanity and the universe loses them, and nothing in the universe compares to a human. The all-around suffering that death causes to the individuals it kills and the people around them is staggering and endlessly traumatic, causing stress and damage on countless levels of every part of life and society. The death process is degrading and undignified, humiliating people for decades as it reduces them to feebleness, senility and dust. Death deprives people of the ability to know what is going on in this mysterious dimension we all find ourselves in here, what we ultimately are and why we are here. It steals away our chance to know what marvels and wonders exist in the expanses of the great unknown, our ability to experience pleasures we haven’t yet, our ability to know what it’s like to experience the fulfillment of all of our goals, and the chance to work for and live in an existence of negligible or perhaps even non-existent fallacy.

We, the freedom loving members of humanity, from all around the globe, of all cultures and creeds, solemnly declare, that we are, and of right ought to be free from death in the form of defined lifespans. To this end we mutually pledge to each other our fortunes and our sacred honor.

The customs of conventions, our current mainstream traditions, are against us, and will be so, until, by a thorough awakening for independence from death, our oldest and most sacred right, takes its rightful and long overdue place among the ranks of other indispensable rights. “The custom of all courts is against us, and will be so, until, by an independance, we take rank with other nations.”

“Wherefore, if they have not virtue enough to be Whigs, they ought to have prudence enough to wish for Independance.” People do not need to want to live for thousands of years in order to want independence from death, they need only want their own freedom to choose what course they may, and the same for their friends and families. Some people don’t want to be forced to live for thousands of years, and some people don’t want to be forced to die before the age of 125. Currently, however, only the people who might choose to die at the age of 50 have the freedom to make that choice. With unlimited lifespans, we can all be free. This is about eradicating deaths tyranny, not death, in the same way that the American revolutionaries worked to break the stranglehold of tyranny that Great Britain held over them, not stop every slight and fight they might have post-independence.

“We fight neither for revenge nor conquest; […] we are not insulting the world with our fleets and armies, nor ravaging the globe for plunder.” Our war is even more dignified. It is removal of a tyranny and the installation of one of the greatest freedoms of all, all without a shedding of blood.

“[L]et a crown be placed thereon, by which the world may know, that so far as we approve of monarchy, that in America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be King; and there ought to be no other.” The ‘law as King’ is superior to ‘humans as Kings’ because people collectively form laws with some amount of oversight of each other’s input. “Law” as the foundation, however, can still tend to be quite arbitrary. Life is what rules us, living, the chance to do people things in a universe of endless opportunities. Let life wear the crown and guide us along our path to true freedom. “The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.” The cause of expanding our frontiers and abilities, of expanding life, is in great measure the greatest cause of them all.