Tag: consciousness

Contrasting Human Futures: Technotopian or Human-Centred?*

[*This article was first published in the September 2017 issue of Paradigm Explorer: The Journal of the Scientific and Medical Network (Established 1973). The article was drawn from the author’s original work in her book: The Future: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017), especially from Chapters 4 & 5.]

We are at a critical point today in research into human futures. Two divergent streams show up in the human futures conversations. Which direction we choose will also decide the fate of earth futures in the sense of Earth’s dual role as home for humans, and habitat for life. I choose to deliberately oversimplify here to make a vital point.

The two approaches I discuss here are informed by Oliver Markley and Willis Harman’s two contrasting future images of human development: ‘evolutionary transformational’ and ‘technological extrapolationist’ in Changing Images of Man (Markley & Harman, 1982). This has historical precedents in two types of utopian human futures distinguished by Fred Polak in The Image of the Future (Polak, 1973) and C. P. Snow’s ‘Two Cultures’ (the humanities and the sciences) (Snow, 1959).

What I call ‘human-centred futures’ is humanitarian, philosophical, and ecological. It is based on a view of humans as kind, fair, consciously evolving, peaceful agents of change with a responsibility to maintain the ecological balance between humans, Earth, and cosmos. This is an active path of conscious evolution involving ongoing psychological, socio-cultural, aesthetic, and spiritual development, and a commitment to the betterment of earthly conditions for all humanity through education, cultural diversity, greater economic and resource parity, and respect for future generations.

By contrast, what I call ‘technotopian futures’ is dehumanising, scientistic, and atomistic. It is based on a mechanistic, behaviourist model of the human being, with a thin cybernetic view of intelligence. The transhumanist ambition to create future techno-humans is anti-human and anti-evolutionary. It involves technological, biological, and genetic enhancement of humans and artificial machine ‘intelligence’. Some technotopians have transcendental dreams of abandoning Earth to build a fantasised techno-heaven on Mars or in satellite cities in outer space.

Interestingly, this contest for the control of human futures has been waged intermittently since at least the European Enlightenment. Over a fifty-year time span in the second half of the 18th century, a power struggle for human futures emerged, between human-centred values and the dehumanisation of the Industrial Revolution.

The German philosophical stream included the idealists and romantics, such as Herder, Novalis, Goethe, Hegel, and Schelling. They took their lineage from Leibniz and his 17th-century integral, spiritually-based evolutionary work. These German philosophers, along with romantic poets such as Blake, Wordsworth and Coleridge (who helped introduce German idealism to Britain) seeded a spiritual-evolutionary humanism that underpins the human-centred futures approach (Gidley, 2007).

The French philosophical influence included La Mettrie’s mechanistic man and René Descartes’s early 17th-century split between mind and body, forming the basis of French (or Cartesian) Rationalism. These French philosophers, La Mettrie and Descartes, along with the theorists of progress such as Turgot and de Condorcet, were secular humanists. Secular humanism is one lineage of technotopian futures. Scientific positivism is another (Gidley, 2017).

Transhumanism, Posthumanism and the Superman Trope

Transhumanism in the popular sense today is inextricably linked with technological enhancement or extensions of human capacities through technology. This is a technological appropriation of the original idea of transhumanism, which began as a philosophical concept grounded in the evolutionary humanism of Teilhard de Chardin, Julian Huxley, and others in the mid-20th century, as we shall see below.

In 2005, the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford founded The Future of Humanity Institute and appointed Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom as its Chair. Bostrom makes a further distinction between secular humanism, concerned with human progress and improvement through education and cultural refinement, and transhumanism, involving ‘direct application of medicine and technology to overcome some of our basic biological limits.’

Bostrom’s transhumanism can enhance human performance through existing technologies, such as genetic engineering and information technologies, as well as emerging technologies, such as molecular nanotechnology and intelligence. It does not entail technological optimism, in that he regularly points to the risks of potential harm, including the ‘extreme possibility of intelligent life becoming extinct’ (Bostrom, 2014). In support of Bostrom’s concerns, renowned theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, and billionaire entrepreneur and engineer Elon Musk have issued serious warnings about the potential existential threats to humanity that advances in ‘artificial super-intelligence’ (ASI) may release.

Not all transhumanists are in agreement, nor do they all share Bostrom’s, Hawking’s and Musk’s circumspect views. In David Pearce’s book The Hedonistic Imperative he argues for a biological programme involving genetic engineering and nanotechnology that will ‘eliminate all forms of cruelty, suffering, and malaise’ (Pearce, 1995/2015). Like the shadow side of the ‘progress narrative’ that has been used as an ideology to support racism and ethnic genocide, this sounds frighteningly like a reinvention of Comte and Spencer’s 19th century Social Darwinism. Along similar lines Byron Reese claims in his book Infinite Progress that the Internet and technology will end ‘Ignorance, Disease, Poverty, Hunger and War’ and we will colonise outer space with a billion other planets each populated with a billion people (Reese, 2013). What happens in the meantime to Earth seems of little concern to them.

One of the most extreme forms of transhumanism is posthumanism: a concept connected with the high-tech movement to create so-called machine super-intelligence. Because posthumanism requires technological intervention, posthumans are essentially a new, or hybrid, species, including the cyborg and the android. The movie character Terminator is a cyborg.

The most vocal of high-tech transhumanists have ambitions that seem to have grown out of the superman trope so dominant in early to mid-20th-century North America. Their version of transhumanism includes the idea that human functioning can be technologically enhanced exponentially, until the eventual convergence of human and machine into the singularity (another term for posthumanism). To popularise this concept Google engineer Ray Kurzweil co-founded the Singularity University in Silicon Valley in 2009. While the espoused mission of Singularity University is to use accelerating technologies to address ‘humanity’s hardest problems’, Kurzweil’s own vision is pure science fiction. In another twist, there is a striking resemblance between the Singularity University logo (below upper) and the Superman logo (below lower).

When unleashing accelerating technologies, we need to ask ourselves, how should we distinguish between authentic projects to aid humanity, and highly resourced messianic hubris? A key insight is that propositions put forward by techno-transhumanists are based on an ideology of technological determinism. This means that the development of society and its cultural values are driven by that society’s technology, not by humanity itself.

In an interesting counter-intuitive development, Bostrom points out that since the 1950s there have been periods of hype and high expectations about the prospect of AI (1950s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s) each followed by a period of setback and disappointment that he calls an ‘AI winter’. The surge of hype and enthusiasm about the coming singularity surrounding Kurzweil’s naïve and simplistic beliefs about replicating human consciousness may be about to experience a fifth AI winter.

The Dehumanization Critique

The strongest critiques of the overextension of technology involve claims of dehumanisation, and these arguments are not new. Canadian philosopher of the electronic age Marshall McLuhan cautioned decades ago against too much human extension into technology. McLuhan famously claimed that every media extension of man is an amputation. Once we have a car, we don’t walk to the shops anymore; once we have a computer hard-drive we don’t have to remember things; and with personal GPS on our cell phones no one can find their way without it. In these instances, we are already surrendering human faculties that we have developed over millennia. It is likely that further extending human faculties through techno- and bio-enhancement will lead to arrested development in the natural evolution of higher human faculties.

From the perspective of psychology of intelligence the term artificial intelligence is an oxymoron. Intelligence, by nature, cannot be artificial and its inestimable complexity defies any notion of artificiality. We need the courage to name the notion of ‘machine intelligence’ for what it really is: anthropomorphism. Until AI researchers can define what they mean by intelligence, and explain how it relates to consciousness, the term artificial intelligence must remain a word without universal meaning. At best, so-called artificial intelligence can mean little more than machine capability, which will always be limited by the design and programming of its inventors. As for machine super-intelligence it is difficult not to read this as Silicon Valley hubris.

Furthermore, much of the transhumanist discourse of the 21st century reflects a historical and sociological naïveté. Other than Bostrom, transhumanist writers seem oblivious to the 3,000-year history of humanity’s attempts to predict, control, and understand the future (Gidley, 2017). Although many transhumanists sit squarely within a cornucopian narrative, they seem unaware of the alternating historical waves of techno-utopianism (or Cornucopianism) and techno-dystopianism (or Malthusianism). This is especially evident in their appropriation and hijacking of the term ‘transhumanism’ with little apparent knowledge or regard for its origins.

Origins of a Humanistic Transhumanism

In 1950, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) published the essay From the Pre-Human to the Ultra-Human: The Phases of a Living Planet, in which he speaks of ‘some sort of Trans-Human at the ultimate heart of things’. Teilhard de Chardin’s Ultra-Human and Trans-Human were evolutionary concepts linked with spiritual/human futures. These concepts inspired his friend Sir Julian Huxley to write about transhumanism, which he did in 1957 as follows [Huxley’s italics]:

The human species can, if it wishes, transcend itself—not just sporadically, an individual here in one way, an individual there in another way—but in its entirety, as humanity. We need a name for this new belief. Perhaps transhumanism will serve: man remaining man, but transcending himself, by realising new possibilities of and for his human nature (Huxley, 1957).

Ironically, this quote is used by techno-transhumanists to attribute to Huxley the coining of the term transhumanism. And yet, their use of the term is in direct contradiction to Huxley’s use. Huxley, a biologist and humanitarian, was the first Director-General of UNESCO in 1946, and the first President of the British Humanist Association. His transhumanism was more humanistic and spiritual than technological, inspired by Teilhard de Chardin’s spiritually evolved human. These two collaborators promoted the idea of conscious evolution, which originated with the German romantic philosopher Schelling.

The evolutionary ideas that were in discussion the century before Darwin were focused on consciousness and theories of human progress as a cultural, aesthetic, and spiritual ideal. Late 18th-century German philosophers foreshadowed the 20th-century human potential and positive psychology movements. To support their evolutionary ideals for society they created a universal education system, the aim of which was to develop the whole person (Bildung in German) (Gidley, 2016).

After Darwin, two notable European philosophers began to explore the impact of Darwinian evolution on human futures, in other ways than Spencer’s social Darwinism. Friedrich Nietzsche’s ideas about the higher person (Übermensch) were informed by Darwin’s biological evolution, the German idealist writings on evolution of consciousness, and were deeply connected to his ideas on freedom.

French philosopher Henri Bergson’s contribution to the superhuman discourse first appeared in Creative Evolution (Bergson, 1907/1944). Like Nietzsche, Bergson saw the superman arising out of the human being, in much the same way that humans have arisen from animals. In parallel with the efforts of Nietzsche and Bergson, Rudolf Steiner articulated his own ideas on evolving human-centred futures, with concepts such as spirit self and spirit man (between 1904 and 1925) (Steiner, 1926/1966). During the same period Indian political activist Sri Aurobindo wrote about the Overman who was a type of consciously evolving future human being (Aurobindo, 1914/2000). Both Steiner and Sri Aurobindo founded education systems after the German bildung style of holistic human development.

Consciously Evolving Human-Centred Futures

There are three major bodies of research offering counterpoints to the techno-transhumanist claim that superhuman powers can only be reached through technological, biological, or genetic enhancement. Extensive research shows that humans have far greater capacities across many domains than we realise. In brief, these themes are the future of the body, cultural evolution and futures of thinking.

Michael Murphy’s book The Future of the Body documents ‘superhuman powers’ unrelated to technological or biological enhancement (Murphy, 1992). For forty years Murphy, founder of Esalen Institute, has been researching what he calls a Natural History of Supernormal Attributes. He has developed an archive of 10,000 studies of individual humans, throughout history, who have demonstrated supernormal experiences across twelve groups of attributes. In almost 800 pages Murphy documents the supernormal capacities of Catholic mystics, Sufi ecstatics, Hindi-Buddhist siddhis, martial arts practitioners, and elite athletes. Murphy concludes that these extreme examples are the ‘developing limbs and organs of our evolving human nature’. We also know from the examples of savants, extreme sport and adventure, and narratives of mystics and saints from the vast literature from the perennial philosophies, that we humans have always extended ourselves—often using little more than the power of our minds.

Regarding cultural evolution, numerous 20th century scholars and writers have put forward ideas about human cultural futures. Ervin László links evolution of consciousness with global planetary shifts (László, 2006). Richard Tarnas in The Passion of the Western Mind traces socio-cultural developments over the last 2,000 years, pointing to emergent changes (Tarnas, 1991). Jürgen Habermas suggests a similar developmental pattern in his book Communication and the Evolution of Society (Habermas, 1979). In the late 1990s Duane Elgin and Coleen LeDrew undertook a forty-three-nation World Values Survey, including Scandinavia, Switzerland, Britain, Canada, and the United States. They concluded, ‘a new global culture and consciousness have taken root and are beginning to grow in the world’. They called it the postmodern shift and described it as having two qualities: an ecological perspective and a self-reflexive ability (Elgin & LeDrew, 1997).

In relation to futures of thinking, adult developmental psychologists have built on positive psychology, and the human potential movement beginning with Abraham Maslow’s book Further Reaches of Human Nature (Maslow, 1971). In combination with transpersonal psychology the research is rich with extended views of human futures in cognitive, emotional, and spiritual domains. For four decades, adult developmental psychology researchers such as Michael Commons, Jan Sinnott, and Lawrence Kohlberg have been researching the systematic, pluralistic, complex, and integrated thinking of mature adults (Commons & Ross, 2008; Kohlberg, 1990; Sinnott, 1998). They call this mature thought ‘postformal reasoning’ and their research provides valuable insights into higher modes of reasoning that are central to the discourse on futures of thinking. Features they identify include complex paradoxical thinking, creativity and imagination, relativism and pluralism, self-reflection and ability to dialogue, and intuition. Ken Wilber’s integral psychology research complements his cultural history research to build a significantly enhanced image of the potential for consciously evolving human futures (Wilber, 2000).

I apply these findings to education in my book Postformal Education: A Philosophy for Complex Futures (Gidley, 2016).

Can AI ever cross the Consciousness Threshold?

Given the breadth and subtlety of postformal reasoning, how likely is it that machines could ever acquire such higher functioning human features? The technotopians discussing artificial superhuman intelligence carefully avoid the consciousness question. Bostrom explains that all the machine intelligence systems currently in use operate in a very narrow range of human cognitive capacity (weak AI). Even at its most ambitious, it is limited to trying to replicate ‘abstract reasoning and general problem-solving skills’ (strong AI). In spite of all the hype around AI and ASI, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute (MIRI)’s own website states that even ‘human-equivalent general intelligence is still largely relegated to the science fiction shelf.’ Regardless of who writes about posthumanism, and whether they are Oxford philosophers, MIT scientists, or Google engineers, they do not yet appear to be aware that there are higher forms of human reasoning than their own. Nor do they have the scientific and technological means to deliver on their high-budget fantasies. Machine super-intelligence is not only an oxymoron, but a science fiction concept.

Even if techno-developers were to succeed in replicating general intelligence (strong AI), it would only function at the level of Piaget’s formal operations. Yet adult developmental psychologists have shown that mature, high-functioning adults are capable of very complex, imaginative, integrative, paradoxical, spiritual, intuitive wisdom—just to name a few of the qualities we humans can consciously evolve. These complex postformal logics go far beyond the binary logic used in coding and programming machines, and it seems also far beyond the conceptual parameters of the AI programmers themselves. I find no evidence in the literature that anyone working with AI is aware of either the limits of formal reasoning or the vast potential of higher stages of postformal reasoning. In short, ASI proponents are entrapped in their thin cybernetic view of intelligence. As such they are oblivious to the research on evolution of consciousness, metaphysics of mind, multiple intelligences, philosophy and psychology of consciousness, transpersonal psychology and wisdom studies, all providing ample evidence that human intelligence is highly complex and evolving.

When all of this research is taken together it indicates that we humans are already capable of far greater powers of mind, emotion, body, and spirit than previously imagined. If we seriously want to develop superhuman intelligence and powers in the 21st century and beyond we have a choice. We can continue to invest heavily in naïve technotopian dreams of creating machines that can operate better than humans. Or we can invest more of our consciousness, energy, and resources on educating and consciously evolving human futures with all the wisdom that would entail.

About Professor Jennifer M. Gidley PhD

Author, psychologist, educator and futurist, Jennifer is a global thought leader and advocate for human-centred futures in an era of hi-tech hype and hubris. She is Adjunct Professor at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, UTS, Sydney and author of The Future: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford, 2017) and Postformal Education: A Philosophy for Complex Futures (Springer, 2016). As former President of the World Futures Studies Federation (2009−2017), a UNESCO and UN ECOSOC partner and global peak body for futures studies, Jennifer led a network of hundreds of the world’s leading futures scholars and researchers from over 60 countries for eight years.

References

[To check references please go to original article in Paradigm Explorer, p. 15–18]

Revita Life Sciences Continues to Advance Multi-Modality Protocol in Attempt to Revive Brain Dead Subjects

Rudrapur, Uttrakhand, India — July 02, 2017

Revita Life Sciences, (http://revitalife.co.in) a biotechnology company focused on translational regenerative therapeutic applications, has announced that it is continuing to advance their novel, multi-modality clinical intervention in the state of brain death in humans.

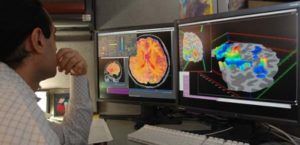

“We have proactively continued to advance our multi-modality protocol, as an extended treatment before extubation, in an attempt to reverse the state of brain death” said Mr.Pranjal Agrawal, CEO Revita Life Sciences. “This treatment approach has yielded some very encouraging initial outcome signs, ranging from minor observations on blood pressure changes with response to painful stimuli, to eye opening and finger movements, with corresponding transient to permanent reversal changes in EEG patterns.”

This first exploratory study, entitled “Non-randomized, Open-labelled, Interventional, Single Group, and Proof of Concept Study with Multi-modality Approach in Cases of Brain Death Due to Traumatic Brain Injury Having Diffuse Axonal Injury” is ongoing at Anupam Hospital, Rudrapur, Uttrakhand. The intervention primarily involves intrathecal administration of minimal manipulated (processed at point of care) autologous stem cells derived from patient’s fat and bone marrow twice a week.

This study was inappropriately removed from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) database. ICMR has no regulatory oversight on such research in India.

The Central Drugs Standard Control Organization (CDSCO), Drug Controller General of India, had no objection to the program progressing. Regulatory approval as needed for new drugs, is currently not required when research is conducted on the recently deceased, although IRB and family consent is definitely required. CDSCO, the regulator of such studies, clearly states that “no regulatory requirements are needed for any study with minimal manipulated autologous stem cells in brain death subjects”.

Death is defined as the termination of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Brain death, the complete and irreversible loss of brain function (including involuntary activity necessary to sustain life) as defined in the 1968 report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School, is the legal definition of human death in most countries around the world. Either directly through trauma, or indirectly through secondary disease indications, brain death is the final pathological state that over 60 million people globally transfer through each year.

“We are in process of publishing our initial retrospective results, as well ongoing early results, in a peer reviewed journal. These initial findings will prove invaluable to the future evolution of the program, as well as in progressing the development multi-modality regenerative therapeutics for the full range of the severe disorders of consciousness, including coma, PVS, the minimally conscious state, and a range of other degenerative CNS conditions in humans,” said Dr. Himanshu Bansal, Chief Scientific Officer, Revita Life Sciences and Director of Mother Cell.

With the maturation of the tools of medical science in the 21st century, especially cell therapies and regenerative medicines, tissues once considered irretrievable, may finally be able to be revived or rejuvenated. Hence many scientists believe that brain death, as presently defined, may one day be reversed. While the very long term goal is to find a solution for “re-infusing life”, the short term purpose of these types of studies is much less dramatic, which is to confirm if the current definition of brain irreversibility still holds true. There have been many anecdotal reports of brain death reversal across the world over the past decades in the scientific literature. Studies of this nature serve to verify and establish this very fact in a scientific and controlled manner. It will also one day give a fair chance to individuals, who are declared brain dead, especially after trauma.

About Revita Life Sciences

Revita Life Sciences is a biotechnology company focused on the development of stem cell therapies and regenerative medicine interventions that target areas of significant unmet medical need. Revita is led by Dr. Himanshu Bansal MD, who has spent over two decades developing novel MRI based classifications of spinal cord injuries as well as comprehensive treatment protocols with autologous tissues including bone marrow stem cells, Dural nerve grafts, nasal olfactory tissues, and omental transposition.

The Science of Consciousness — Helané Wahbeh | Institute of Noetic Sciences

[youtube_sc url=“https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AnFUZVvQqhQ”]

“While our materialistic paradigm would have us believe that our consciousness is housed in our physical brain and does not extend beyond it, there is growing evidence that this is actually not true.”

Dr. Ken Hayworth, Part 3: If we can build a brain, what is the future of I?

The study of consciousness and what makes us individuals is a topic filled with complexities. From a neuroscience perspective, consciousness is derived from a self-model as a unitary structure that shapes our perceptions, decisions and feelings. There is a tendency to jump to the conclusion with this model that mankind is being defined as self-absorbed and only being in it for ourselves in this life. Although that may be partially true, this definition of consciousness doesn’t necessarily address the role of morals and how that is shaped into our being. In the latest addition to The Galactic Public Archives, Dr. Ken Hayworth tackles the philosophical impact that technologies have on our lives.

Our previous two films feature Dr. Hayworth extrapolating about what radical new technologies in neuroscience could eventually produce. In a hypothetical world where mind upload is possible and we could create a perfect replica of ourselves, how would one personally identify? If this copy has the same memories and biological components, our method of understanding consciousness would inevitably shift. But when it comes down it, if we were put in a situation where it would be either you or the replica – it’s natural evolutionary instinct to want to save ourselves even if the other is an exact copy. This notion challenges the idea that our essence is defined by our life experiences because many different people can have identical experiences yet react differently.

Hayworth explains, that although there is an instinct for self-survival, humanity for the most part, has a basic understanding not to cause harm upon others. This is because morals are not being developed in the “hard drive” of your life experiences; instead our morals are tied to the very idea of someone just being a conscious and connected member of this world. Hayworth rationalizes that once we accept our flawed intuition of self, humanity will come to a spiritual understanding that the respect we give to others for simply possessing a reflection of the same kind of consciousness will be the key to us identifying our ultimate interconnectedness.

For now, the thought experiments featured in this third film remain firmly in the realm of science fiction. But as science fiction progresses closer to “science fact”, there is much to be considered about how our personal and societal values will inevitably shift — even if none of us needs to start worrying about where we’ve stored our back up memories just yet.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to mankind as is, Infinite.”

-William Blake

Human Brain Mapping & Simulation Projects: America Wants Some, Too?

The Brain Games Begin

Europe’s billion-Euro science-neuro Human Brain Project, mentioned here amongst machine morality last week, is basically already funded and well underway. Now the colonies over in the new world are getting hip, and they too have in the works a project to map/simulate/make their very own copy of the universe’s greatest known computational artifact: the gelatinous wad of convoluted electrical pudding in your skull.

The (speculated but not yet public) Brain Activity Map of America

About 300 different news sources are reporting that a Brain Activity Map project is outlined in the current administration’s to-be-presented budget, and will be detailed sometime in March. Hoards of journalists are calling it “Obama’s Brain Project,” which is stoopid, and probably only because some guy at the New Yorker did and they all decided that’s what they had to do, too. Or somesuch lameness. Or laziness? Deference? SEO?

For reasons both economic and nationalistic, America could definitely use an inspirational, large-scale scientific project right about now. Because seriously, aside from going full-Pavlov over the next iPhone, what do we really have to look forward to these days? Now, if some technotards or bible pounders monkeywrench the deal, the U.S. is going to continue that slide toward scientific… lesserness. So, hippies, religious nuts, and all you little sociopathic babies in politics: zip it. Perhaps, however, we should gently poke and prod the hard of thinking toward a marginally heightened Europhobia — that way they’ll support the project. And it’s worth it. Just, you know, for science.

Going Big. Not Huge, But Big. But Could be Massive.

Both the Euro and American flavors are no Manhattan Project-scale undertaking, in the sense of urgency and motivational factors, but more like the Human Genome Project. Still, with clear directives and similar funding levels (€1 billion Euros & $1–3 billion US bucks, respectively), they’re quite ambitious and potentially far more world changing than a big bomb. Like, seriously, man. Because brains build bombs. But hopefully an artificial brain would not. Spaceships would be nice, though.

Practically, these projects are expected to expand our understanding of the actual physical loci of human behavioral patterns, get to the bottom of various brain pathologies, stimulate the creation of more advanced AI/non-biological intelligence — and, of course, the big enchilada: help us understand more about our own species’ consciousness.

On Consciousness: My Simulated Brain has an Attitude?

Yes, of course it’s wild speculation to guess at the feelings and worries and conundrums of a simulated brain — but dude, what if, what if one or both of these brain simulation map thingys is done well enough that it shows signs of spontaneous, autonomous reaction? What if it tries to like, you know, do something awesome like self-reorganize, or evolve or something?

Maybe it’s too early to talk personality, but you kinda have to wonder… would the Euro-Brain be smug, never stop claiming superior education yet voraciously consume American culture, and perhaps cultivate a mild racism? Would the ‘Merica-Brain have a nation-scale authority complex, unjustifiable confidence & optimism, still believe in childish romantic love, and overuse the words “dude” and “awesome?”

We shall see. We shall see.

Oh yeah, have to ask:

Anyone going to follow Ray Kurzweil’s recipe?

Project info:

[HUMAN BRAIN PROJECT - € - MAIN SITE]

[THE BRAIN ACTIVITY MAP - $ - HUFF-PO]

Kinda Pretty Much Related:

[BLUE BRAIN PROJECT]

This piece originally appeared at Anthrobotic.com on February 28, 2013.

Machine Morality: a Survey of Thought and a Hint of Harbinger

The Golden Rule is Not for Toasters

Simplistically nutshelled, talking about machine morality is picking apart whether or not we’ll someday have to be nice to machines or demand that they be nice to us.

Well, it’s always a good time to address human & machine morality vis-à-vis both the engineering and philosophical issues intrinsic to the qualification and validation of non-biological intelligence and/or consciousness that, if manifested, would wholly justify consideration thereof.

Uhh… yep!

But, whether at run-on sentence dorkville or any other tech forum, right from the jump one should know that a single voice rapping about machine morality is bound to get hung up in and blinded by its own perspective, e.g., splitting hairs to decide who or what deserves moral treatment (if a definition of that can even be nailed down), or perhaps yet another justification for the standard intellectual cul de sac:

“Why bother, it’s never going to happen.“

That’s tired and lame.

One voice, one study, or one robot fetishist with a digital bullhorn — one ain’t enough. So, presented and recommended here is a broad-based overview, a selection of the past year’s standout pieces on machine morality.The first, only a few days old, is actually an announcement of intent that could pave the way to forcing the actual question.

Let’s then have perspective:

Building a Brain — Being Humane — Feeling our Pain — Dude from the NYT

• February 3, 2013 — Human Brain Project: Simulate One

Serious Euro-Science to simulate a human brain. Will it behave? Will we?

• January 28, 2013 — NPR: No Mercy for Robots

A study of reciprocity and punitive reaction to non-human actors. Bad robot.

• April 25, 2012 — IEEE Spectrum: Attributing Moral Accountability to Robots

On the human expectation of machine morality. They should be nice to me.

• December 25, 2011 — NYT: The Future of Moral Machines

Engineering (at least functional) machine morality. Broad strokes NYT-style.

Expectations More Human than Human?

Now, of course you’re going to check out those pieces you just skimmed over, after you finish trudging through this anti-brevity technosnark©®™ hybrid, of course. When you do — you might notice the troubling rub of expectation dichotomy. Simply put, these studies and reports point to a potential showdown between how we treat our machines, how we might expect others to treat them, and how we might one day expect to be treated by them. For now morality is irrelevant, it is of no consideration nor consequence in our thoughts or intentions toward machines. But, at the same time we hold dear the expectation of reasonable treatment, if not moral, by any intelligent agent — even an only vaguely human robot.

Well what if, for example: 1. AI matures, and 2. machines really start to look like us?

(see: Leaping Across Mori’s Uncanny Valley: Androids Probably Won’t Creep Us Out)

Even now should someone attempt to smash your smartphone or laptop (or just touch it), you of course protect the machine. Extending beyond concerns over the mere destruction of property or loss of labor, could one morally abide harm done to one’s marginally convincing humanlike companion? Even if fully accepting of its artificiality, where would one draw the line between economic and emotional damage? Or, potentially, could the machine itself abide harm done to it? Even if imbued with a perfectly coded algorithmic moral code mandating “do no harm,” could a machine calculate its passive non-response to intentional damage as an immoral act against itself, and then react?

Yeah, these hypotheticals can go on forever, but it’s clear that blithely ignoring machine morality or overzealously attempting to engineer it might result in… immorality.

Probably Only a Temporary Non-Issue. Or Maybe. Maybe Not.

There’s an argument that actually needing to practically implement or codify machine morality is so remote that debate is, now and forever, only that — and oh wow, that opinion is superbly dumb. This author has addressed this staggeringly arrogant species-level macro-narcissism before (and it was awesome). See, outright dismissal isn’t a dumb argument because a self-aware machine or something close enough for us to regard as such is without doubt going to happen, it’s dumb because 1. absolutism is fascist, and 2. to the best of our knowledge, excluding the magic touch of Jesus & friends or aliens spiking our genetic punch or whatever, conscious and/or self-aware intelligence (which would require moral consideration) appears to be an emergent trait of massively powerful computation. And we’re getting really good at making machines do that.

Whatever the challenge, humans rarely avoid stabbing toward the supposedly impossible — and a lot of the time, we do land on the moon. The above mentioned Euro-project says it’ll need 10 years to crank out a human brain simulation. Okay, respectable. But, a working draft of the human genome, an initially 15-year international project, was completed 5 years ahead of schedule due largely to advances in brute force computational capability (in the not so digital 1990s). All that computery stuff like, you know, gets better a lot faster these days. Just sayin.

So, you know, might be a good idea to keep hashing out ideas on machine morality.

Because who knows what we might end up with…

“Oh sure, I understand, turn me off, erase me — time for a better model, I totally get it.“

- or -

“Hey, meatsack, don’t touch me or I’ll reformat your squishy face!”

Choose your own adventure!

[HUMAN BRAIN PROJECT]

[NO MERCY FOR ROBOTS — NPR]

[ATTRIBUTING MORAL ACCOUNTABILITY TO ROBOTS — IEEE]

[THE FUTURE OF MORAL MACHINES — NYT]

This piece originally appeared at Anthrobotic.com on February 7, 2013.

D’Nile aint just a river in Egypt…

Greetings fellow travelers, please allow me to introduce myself; I’m Mike ‘Cyber Shaman’ Kawitzky, independent film maker and writer from Cape Town, South Africa, one of your media/art contributors/co-conspirators.

It’s a bit daunting posting to such an illustrious board, so let me try to imagine, with you; how to regard the present with nostalgia while looking look forward to the past, knowing that a millisecond away in the future exists thoughts to think; it’s the mode of neural text, reverse causality, non-locality and quantum entanglement, where the traveller is the journey into a world in transition; after 9/11, after the economic meltdown, after the oil spill, after the tsunami, after Fukushima, after 21st Century melancholia upholstered by anti-psychotic drugs help us forget ‘the good old days’; because it’s business as usual for the 1%; the rest continue downhill with no brakes. Can’t wait to see how it all works out.

Please excuse me, my time machine is waiting…