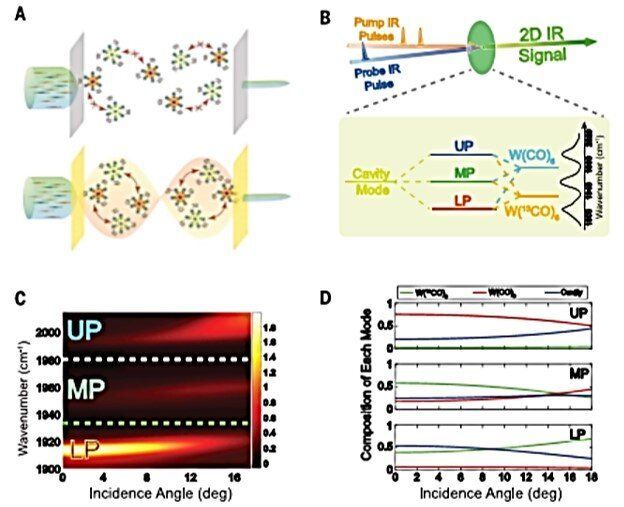

Strong coupling between cavity photon modes and donor/acceptor molecules can form polaritons (hybrid particles made of a photon strongly coupled to an electric dipole) to facilitate selective vibrational energy transfer between molecules in the liquid phase. The process is typically arduous and hampered by weak intermolecular forces. In a new report now published on Science, Bo Xiang, and a team of scientists in materials science, engineering and biochemistry at the University of California, San Diego, U.S., reported a state-of-the-art strategy to engineer strong light-matter coupling. Using pump-probe and two-dimensional (2-D) infrared spectroscopy, Xiang et al. found that strong coupling in the cavity mode enhanced the vibrational energy transfer of two solute molecules. The team increased the energy transfer by increasing the cavity lifetime, suggesting the energy transfer process to be a polaritonic process. This pathway on vibrational energy transfer will open new directions for applications in remote chemistry, vibration polariton condensation and sensing mechanisms.

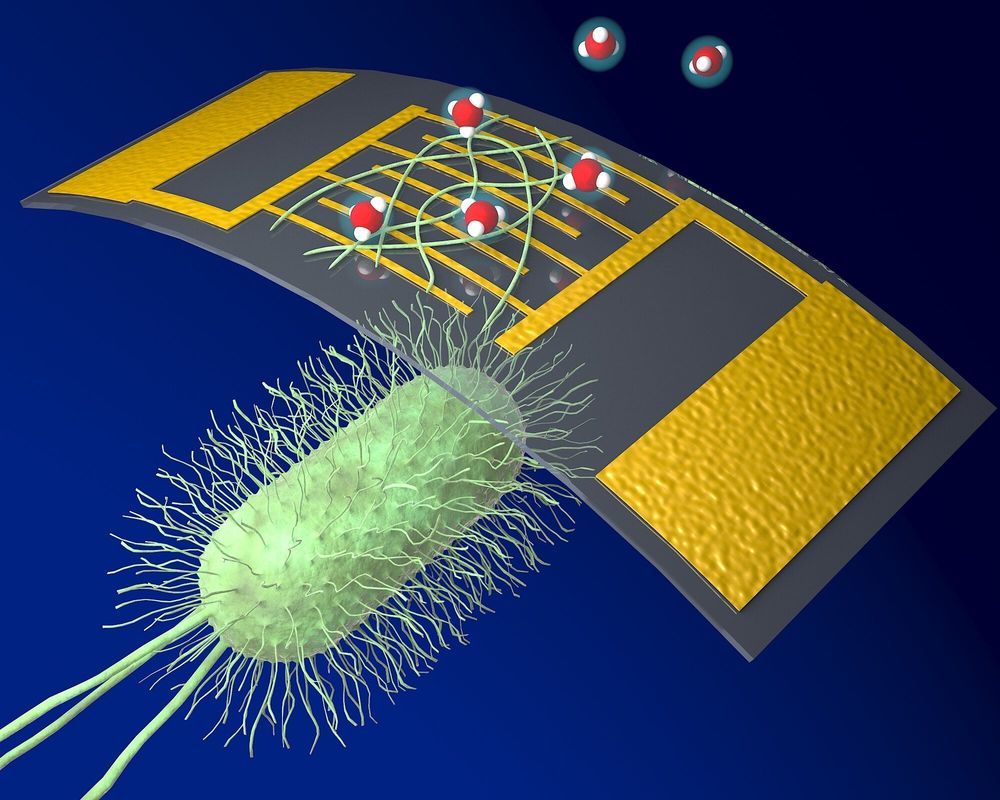

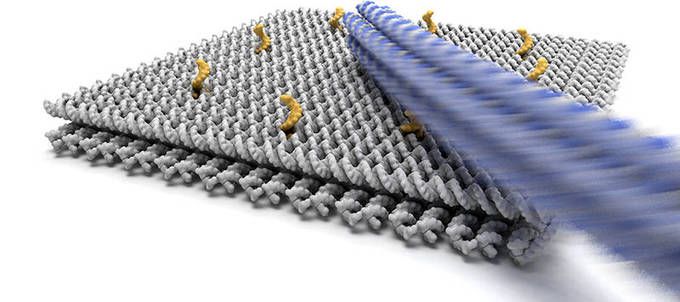

Vibrational energy transfer (VET) is a universal process ranging from chemical catalysis to biological signal transduction and molecular recognition. Selective intermolecular vibrational energy transfer (VET) from solute-to-solute is relatively rare due to weak intermolecular forces. As a result, intermolecular VET is often unclear in the presence of intramolecular vibrational redistribution (IVR). In this work, Xiang et al. detailed a state-of-the-art method to engineer intermolecular vibrational interactions via strong light-matter coupling. To accomplish this, they inserted a highly concentrated molecular sample into an optical microcavity or placed it onto a plasmonic nanostructure. The confined electromagnetic modes in the setup then reversibly interacted with collective macroscopic molecular vibrational polarization for hybridized light-matter states known as vibrational polaritons.