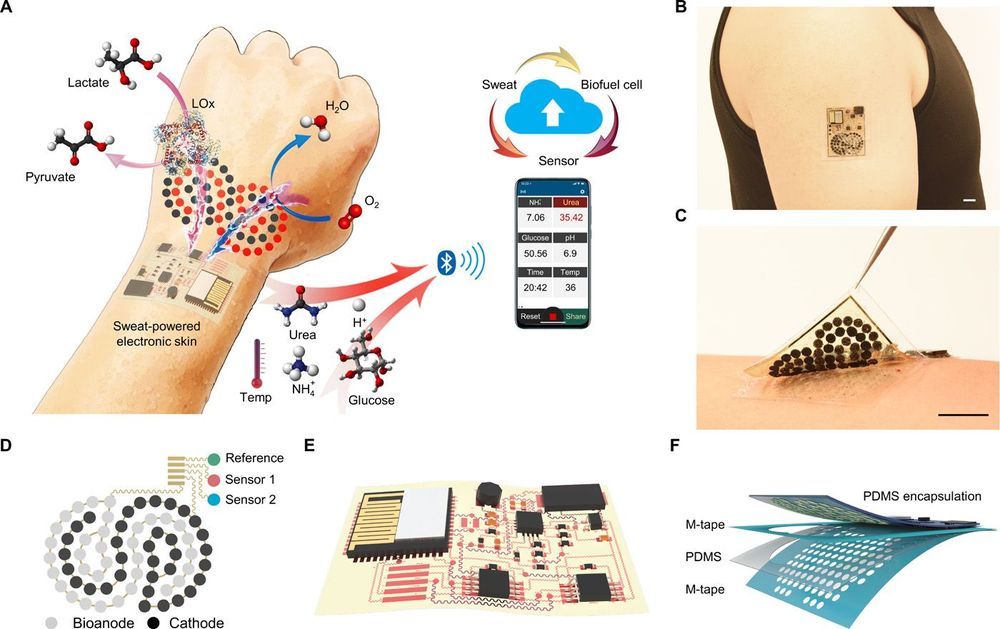

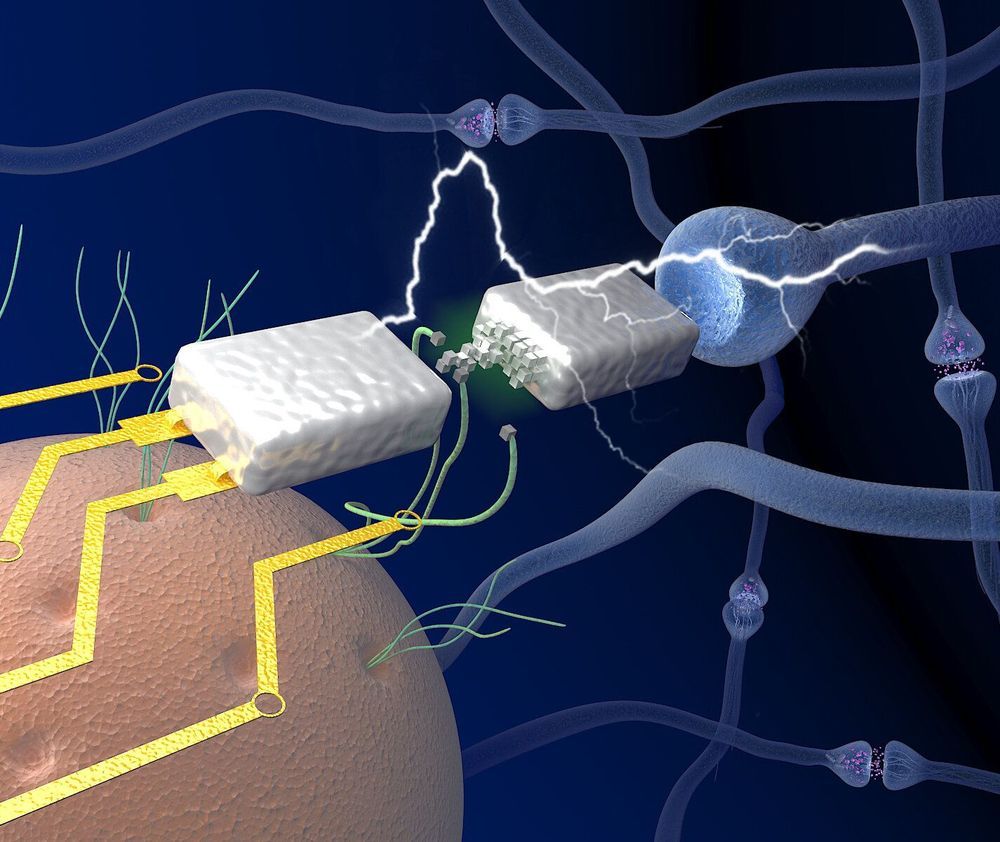

Existing electronic skin (e-skin) sensing platforms are equipped to monitor physical parameters using power from batteries or near-field communication. For e-skins to be applied in the next generation of robotics and medical devices, they must operate wirelessly and be self-powered. However, despite recent efforts to harvest energy from the human body, self-powered e-skin with the ability to perform biosensing with Bluetooth communication are limited because of the lack of a continuous energy source and limited power efficiency. Here, we report a flexible and fully perspiration-powered integrated electronic skin (PPES) for multiplexed metabolic sensing in situ. The battery-free e-skin contains multimodal sensors and highly efficient lactate biofuel cells that use a unique integration of zero- to three-dimensional nanomaterials to achieve high power intensity and long-term stability. The PPES delivered a record-breaking power density of 3.5 milliwatt·centimeter−2 for biofuel cells in untreated human body fluids (human sweat) and displayed a very stable performance during a 60-hour continuous operation. It selectively monitored key metabolic analytes (e.g., urea, NH4+, glucose, and pH) and the skin temperature during prolonged physical activities and wirelessly transmitted the data to the user interface using Bluetooth. The PPES was also able to monitor muscle contraction and work as a human-machine interface for human-prosthesis walking.

Recent advances in robotics have enabled soft electronic devices at different scales with excellent biocompatibility and mechanical properties; these advances have rendered novel robotic functionalities suitable for various medical applications, such as diagnosis and drug delivery, soft surgery tools, human-machine interaction (HMI), wearable computing, health monitoring, assistive robotics, and prosthesis (1–6). Electronic skin (e-skin) can have similar characteristics to human skin, such as mechanical durability and stretchability and the ability to measure various sensations such as temperature and pressure (7–11). Moreover, e-skin can be augmented with capabilities beyond those of the normal human skin by incorporating advanced bioelectronics materials and devices.