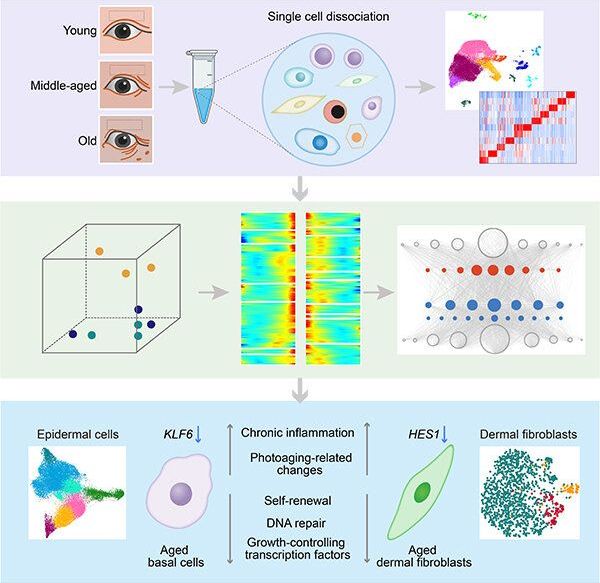

**Peroxisomes are compartments where cells turn fatty molecules into energy and useful materials, like the myelin sheaths that protect nerve cells. In humans, peroxisome dysfunction has been linked to severe metabolic disorders, and peroxisomes may have wider significance for neurodegeneration, obesity, cancer and age-related disorders.**

Peroxisomes are also highly conserved, from plants to yeast to humans, and Bartel said there are hints that these structures may be general features of peroxisomes.

“Peroxisomes are a basic organelle that has been with eukaryotes for a very long time, and there have been observations across eukaryotes, often in particular mutants, where the peroxisomes are either bigger or less packed with proteins, and thus easier to visualize,” she said. But people didn’t necessarily pay attention to those observations because the enlarged peroxisomes resulted from known mutations.

The researchers aren’t sure what purpose is served by the subcompartments, but Wright has a hypothesis.

“When you’re talking about things like beta-oxidation, or metabolism of fats, you get to the point that the molecules don’t want to be in water anymore,” Wright said. “When you think of a traditional kind of biochemical reaction, we just have a substrate floating around in the water environment of a cell—the lumen—and interacting with enzymes; that doesn’t work so well if you’ve got something that doesn’t want to hang around in the water.”

“So, if you’re using these membranes to solubilize the water-insoluble metabolites, and allow better access to lumenal enzymes, it may represent a general strategy to more efficiently deal with that kind of metabolism,” he said.

Bartel said the discovery also provides a new context for understanding peroxisomal disorders.

“This work could give us a way to understand some of the symptoms, and potentially to investigate the biochemistry that’s causing them,” she said.

In his first year of graduate school, Rice University biochemist Zachary Wright discovered something hidden inside a common piece of cellular machinery that’s essential for all higher order life from yeast to humans.

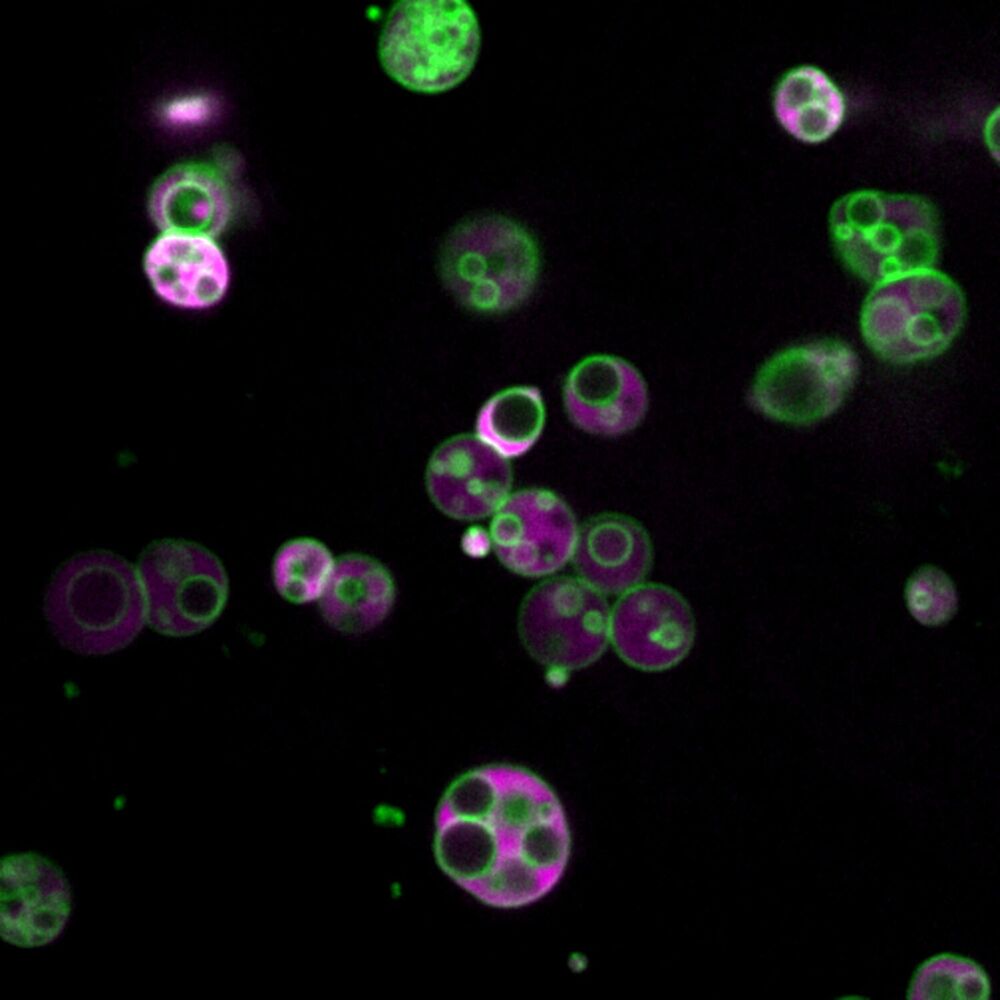

What Wright saw in 2015—subcompartments inside organelles called peroxisomes—is described in a study published today in Nature Communications.

“This is, without a doubt, the most unexpected thing our lab has ever discovered,” said study co-author Bonnie Bartel, Wright’s Ph.D. advisor and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. “This requires us to rethink everything we thought we knew about peroxisomes.”