“In our current study we were able to uncover important limitations for the use of metformin as longevity medicine,” says Dr. Ermolaeva. In contrast to the positive longevity effects in young organisms that received metformin, lifespan is shortened through metformin intake at an older age. “Previous studies that provided evidence of an extended longevity by metformin usually examined animals treated with metformin from young adult or middle age until the end of life. In contrast, we have looked at treatment windows covering the entire life span, or restricted to early life or to late life”. The study also utilized a human cell culture model of replicative aging to assess human responses to metformin at a cellular level and compare them to organismal responses of the worms.

**Metformin longevity benefits are reversed with age**

The research team led by Dr. Ermolaeva found that the very same metformin treatment that prolonged life when C. elegans worms were treated at young age, was highly toxic when animals of old age were treated. Up to 80% of the population treated at old age were killed by metformin within the first 24 hours of treatment. Consistently, human primary cells demonstrated a progressive decrease in metformin tolerance as they approached replicative senescence. The researchers were able to link this detrimental phenotype to the reduced ability of old cells and old nematodes to adapt to metabolic stressors like metformin. Under these circumstances, the exact same dose of the drug that increased longevity of young-treated organisms by triggering adaptive stress responses was harmful in animals treated at old age, which were unable to activate such protective signals.

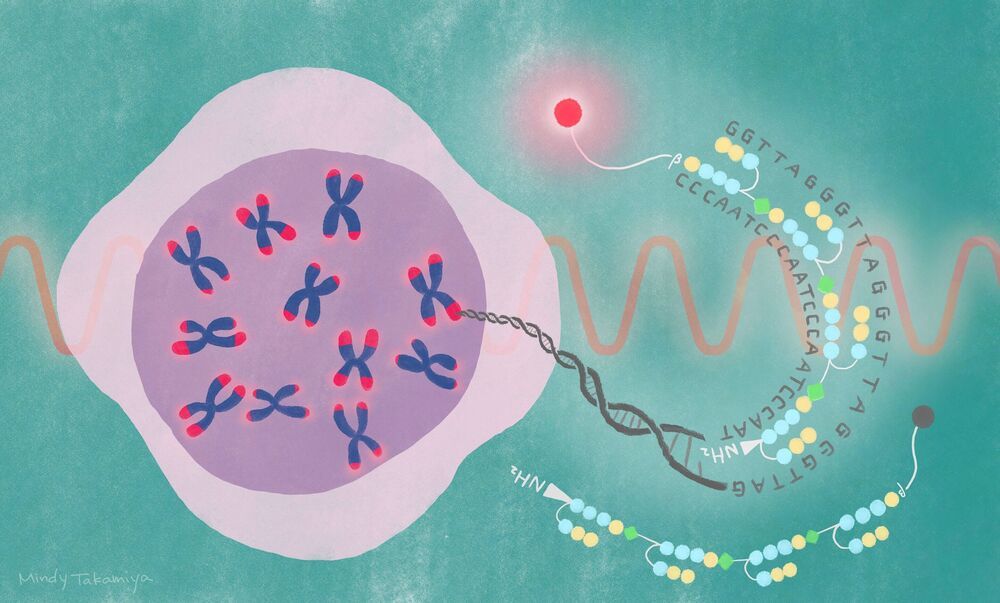

Metformin is a common type 2 diabetes drug. Recently, it was found to extend life span of young non-diabetic animals but the responses of older organisms to metformin remain unexplored. Researchers at the Leibniz Institute on Aging—Fritz Lipmann Institute (FLI) in Jena, Germany, and the Friedrich Schiller University Jena found that mitochondrial dysfunction abrogates metformin benefits in aged C. elegans and late passage human cells. Moreover, the same metformin regime that prolongs the lifespan of young nematodes was toxic in old animals by inducing deleterious metabolic changes. These findings suggest that aging sets a limit for the health span benefits of metformin outside of diabetes.

While people today are getting older and older, diseases that are associated with age (e.g. cardiovascular diseases, cancer, dementia and diabetes) are also increasing. Reaching late life while staying healthy is of high priority. Recently, the drug metformin, which has been used for decades to treat patients suffering from type 2 diabetes, was linked to the reduced risk of cancer development and showed potential to alleviate cardiovascular diseases in humans. Furthermore, a life-prolonging effect of metformin has recently been shown in mice, flies and worms. So, does this make metformin the new miracle drug to prolong life and even delay aging-associated diseases?

The first clinical testing of a potential life-prolonging effect of metformin in aged humans without diabetes has been initiated by the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR). However, the long-term effects of metformin in a non-diabetic cohort at different age have not been investigated yet. Researchers at the Leibniz Institute on Aging—Fritz Lipmann Institute (FLI) in Jena, and their colleagues from the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (FSU), Germany, have now addressed these questions. They used the nematode C. elegans and human primary cells to investigate the metabolic response of young and old non-diabetic organisms to metformin treatment in detail. The current study has now been published in the journal Nature Metabolism.