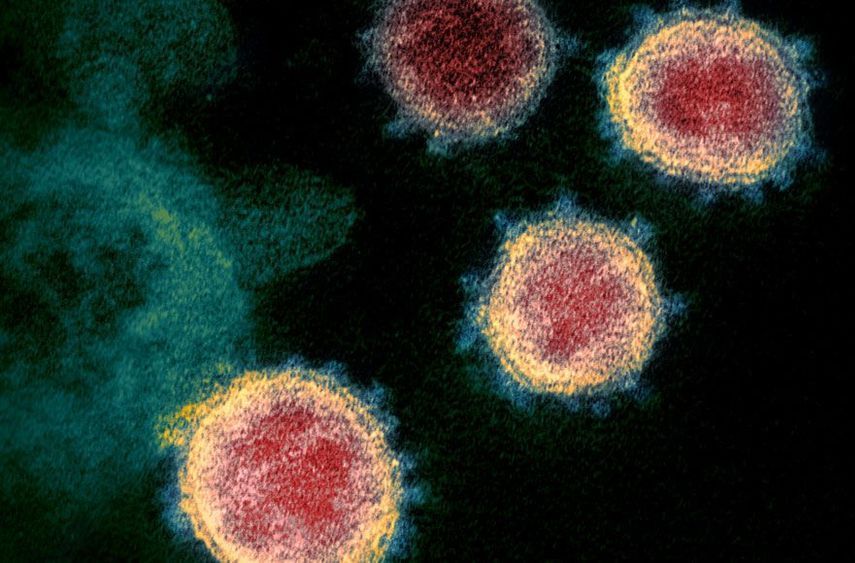

Scientists took conspiracy theories seriously and analyzed the coronavirus to reveal its natural origins.

:ooooo.

Unlocking the full potential of cannabis for agriculture and human health will require a co-ordinated scientific effort to assemble and map the cannabis genome, says a just-published international study led by University of Saskatchewan researchers.

In a major statistical analysis of existing data and studies published in the Annual Review of Plant Biology, the authors conclude there are large gaps in the scientific knowledge of this high-demand, multi-purpose crop.

“Considering the importance of genomics in the development of any crop, this analysis underlines the need for a co-ordinated effort to quantify the genetic and biochemical diversity of this species,” the authors state.

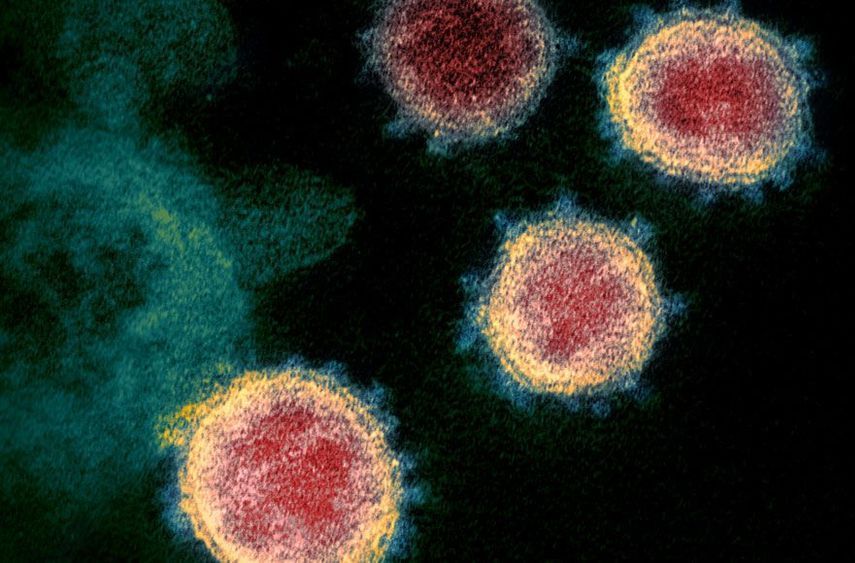

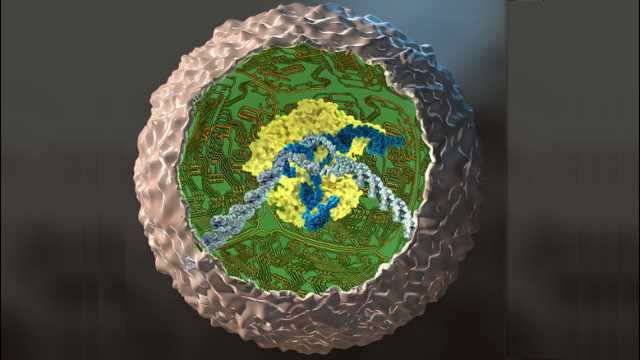

Researchers have developed the first computational model of a human cell and simulated its behavior for 15 minutes—the longest time achieved for a biological system of this complexity. In a new study, simulations reveal the effects of spatial organization within cells on some of the genetic processes that control the regulation and development of human traits and some human diseases.

The study, which produced a new computational platform that is available to any researcher, is published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

“This is the first program that allows researchers to set up a virtual human cell and change chemical reactions and geometries to observe cellular processes in real time,” said Zhaleh Ghaemi, a research scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and lead author of the study.

The Curious Case of Sickle-Cell Anemia

Even those uninterested in biology have likely heard of the disorder. Sickle-cell anemia holds the crown as the first genetic disorder to be traced to its molecular roots nearly a hundred years ago.

The root of the disorder is a single genetic mutation that drastically changes the structure of the oxygen-carrying protein, beta-globin, in red blood cells. The result is that the cells, rather than forming their usual slick disc-shape, turn into jagged, sickle-shaped daggers that damage blood vessels or block them altogether. The symptoms aren’t always uniform; rather, they come in “crisis episodes” during which the pain becomes nearly intolerable.

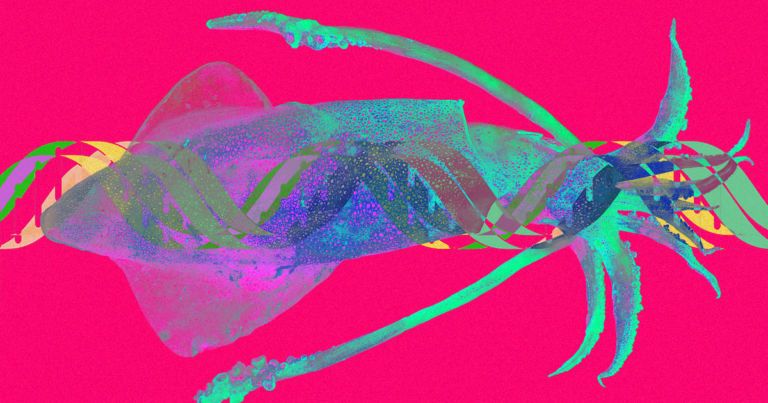

The longfin inshore squid can edit the RNA inside its nerve cells, Wired reports, meaning that it can drastically alter the behavior of its biological machinery as needed — perhaps to help the animal rapidly adapt to new environments. It’s a bizarre discovery, and one that could potentially lead to better genetic treatments for humans.

Neat Trick

Researchers from the Marine Biological Laboratory found that the squid alters the RNA within its axons instead of the DNA within its nuclei, according to research published Monday in the journal Nucleic Acids Research. Thus far, it’s the only animal known to do so.

Using new gene-editing technology, researchers have rewired mouse stem cells to fight inflammation caused by arthritis and other chronic conditions. Such stem cells, known as SMART cells (Stem cells Modified for Autonomous Regenerative Therapy), develop into cartilage cells that produce a biologic anti-inflammatory drug that, ideally, will replace arthritic cartilage and simultaneously protect joints and other tissues from damage that occurs with chronic inflammation.

Coronavirus RNA survived for up to 17 days aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship, living far longer on surfaces than previous research has shown, according to new data published Monday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The study examined the Japanese and U.S. government efforts to contain the COVID-19 outbreaks on the Carnival-owned Diamond Princess ship in Japan and the Grand Princess ship in California. Passengers and crew on both ships were quarantined on board after previous guests, who didn’t have any symptoms while aboard each of the ships, tested positive for COVID-19 after landing ashore.

The RNA, the genetic material of the virus that causes COVID-19, “was identified on a variety of surfaces in cabins of both symptomatic and asymptomatic infected passengers up to 17 days after cabins were vacated on the Diamond Princess but before disinfection procedures had been conducted,” the researchers wrote, adding that the finding doesn’t necessarily mean the virus spread by surface.

Revealing yet another super-power in the skillful squid, scientists have discovered that squid massively edit their own genetic instructions not only within the nucleus of their neurons, but also within the axon — the long, slender neural projections that transmit electrical impulses to other neurons. This is the first time that edits to genetic information have been observed outside of the nucleus of an animal cell.

The study, led by Isabel C. Vallecillo-Viejo and Joshua Rosenthal at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, is published this week in Nucleic Acids Research.

The discovery provides another jolt to the “central dogma” of molecular biology, which states that genetic information is passed faithfully from DNA to messenger RNA to the synthesis of proteins. In 2015, Rosenthal and colleagues discovered that squid “edit” their messenger RNA instructions to an extraordinary degree — orders of magnitude more than humans do — allowing them to fine-tune the type of proteins that will be produced in the nervous system.

The genetic information of an organism is stored within DNA. It contains the code for making other molecules that make all cells and organs of the body functional. Interestingly, only 1% of DNA makes up genes, of which proteins are produced via RNA intermediaries. There is much debate on the role of the remaining DNA, but different types of RNA are thought to be produced from it and direct the fate of the cell. Even though each cell of the body contains the same DNA, how they read and process DNA to make RNA can differ quite dramatically between single cells. This has especially been known for the transcriptome, which includes all RNA that are produced from genes, but not so much for other RNA.

“Genes have been the main focus of biological research for a long time,” says lead author of the study Haruka Ozaki. “We wanted to focus on what we call read coverage of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, which also includes RNA that are not products of genes. Although we can measure the amount of different RNA a single cell produces by scRNA-seq technologies, we wanted to come up with a new method that also visualizes specifically read coverage, because only then we can get a full picture of RNA biology and how it contributes to cell biology at the single-cell level.”

To achieve their goal, the researchers developed a new computational tool that they called Millefy uses existing scRNA-seq data to visualize read coverage of single cells as a heat map, illustrating differences between individual cells on a relative scale. The researchers first demonstrated the utility of Millefy in a well-established mouse embryonic stem cell model by showing heterogeneity of read coverage between developing cells. They then applied Millefy to cancer cells from patients with triple-negative breast cancer, a particularly aggressive type of breast cancer. Not only did Millefy show heterogeneity between cancer cells in general, but it revealed heterogeneity in a specific aspect of RNA biology that had previously been unknown.

“Our approach simplifies the investigation of cellular heterogeneity in RNA biology using scRNA-seq data,” says Ozaki. ” Our findings could help identify what makes single cells individual, which would help us understand why patients with the same disease are often treated with varying success. Additionally, to enable rapid progress in field, we made Millefy publicly available to the scientific community.”