How has your work, your life, your humanity, been improved by the promise of Big Data?

What apps and online media do you use to upload personal and other info?

Singularity has flopped – that is to say, this week Johnny Depp’s new film Transcendence did not bring in as much as Pirates of the Caribbean. Though there may not have been big box office heat, there is heat behind the film’s subject: Big Data! Sure we miss seeing our affable pirate chasing treasure, but hats off to Mr. Depp who removed his Keith Richards make-up to risk chasing what might be the mightiest challenge of our century.

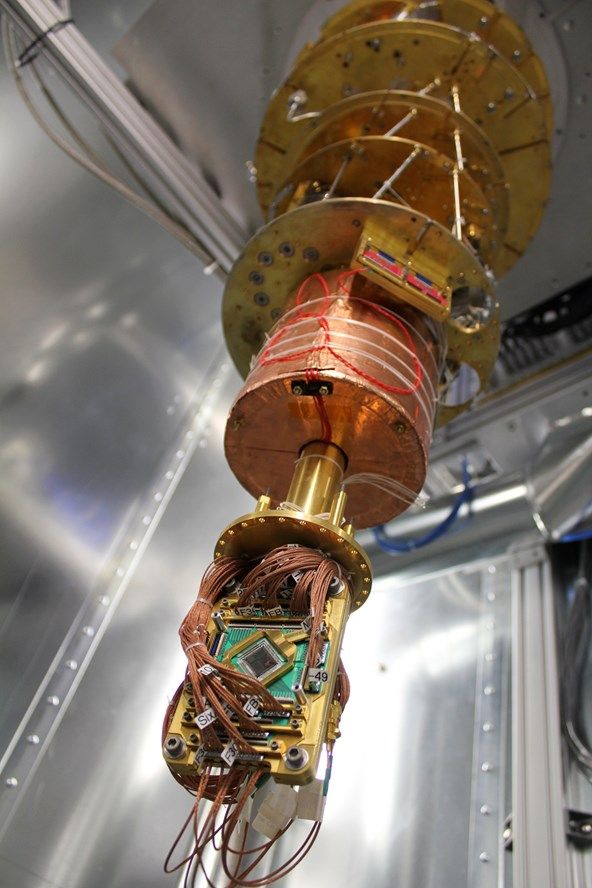

Singularity, coined by mathematician John von Neumann, is a heady mathematical concept tested by biotech predictions. Made popular by math and music wunderkindt turned gray hair guru of an AI movement Ray Kurzweil, Singularity is said to signify the increasing rate at which artificial intelligence will supersede human intelligence like a jealous sibling. Followers of the Singularity movement (yes, with guru comes followers) envision the time of override in the not to distant future with projections set early as 2017 and 2030. At these times, the dynamics of technology are said to set about a change in our biology, our civilization and “perhaps” nature itself. Within our current reach, we see signs of empowered tech acting out in the current human brain mapping quest and brain-computer interface systems. More to the point, there is an ever increasing onslaught of Google Alerts annoucing biotech enhancements with wearable tech. Yes indeed, here comes the age of smart prosthetics and our own AI upload of medical and personal data to the internet. Suddenly all those Selfies seem more than mere narcissistic postings against the imposing backdrop of Big Data.

Johnny Depp’s face says it all in Transcendence where Big Data determines our AI future wherein life as we know it, can and will exist online. Think beyond a 24/7 teenage plug into a smart phone or flash- driving Facebook entries. Think Neuromancer, VALIS, and Star Trek’s Borg — sci fi predecessors predicting memory transformations amounting to an existential reboot. Translated into the everyday, we’re talking more than just uploading your genetic code to 23andme. This is an imagined future where what we call “Me” will be psychologically and legally recognized as living online.

As a contemporary sci fi, Transcendence is filled with pentimento film tributes to Zombie and X-Men TakeOvers, Westerns and Romantic Tragedies. Pitting AI critics against AI visionaries, the film is a bioethics drama, where the prospect of creating online Selves will constitute a direct social threat with thoroughgoing eco consequences. At the center of the bioethics contest, we encounter the marriage and business partnership of Will and Eleanor Castor — the heroic scientist and the eco-activist whose death do us part vows are broken to unleash a future so thoroughly transformed by AI as to render biological existence “hacked” by internet code.

The romantic hubris of Transcendence is jolting with a Shakespearean twist: Dare to Upload yourself to the internet and threaten genealogy, global power. Wait, this is no Romeo and Juliet. Love and Death, Eros and Thanatos, as Herr Freud called it, stands at the center of this science fiction pivoting on Will Castor’s heroic martyrdom (played astutely by Johnny Depp). By the end of the film, we are forced to face the movie’s existential questions as moral and medical ones. With new sentient life living online, collective imagination for our biohumanity and ecosystem is left unhinged.

Image Credit: Transcendence, 2014 Original Soundtrack

While the film lifts common AI themes of transformed “self-awareness” and “identity,” the real AI deal breaker in Transcendence, and in our own lives, is Time – biological, ecological and geologic. Described as a sequential and cyclical process, Time frames our present experience, shaping both memory and imagination of that present experience. As my Buddhist philosophy professor use to say: “When you are waiting for your lover, 10 minutes feels like 1 hour; but when your lover arrives, 1 hour feels like 10 minutes.” Cognitive neuroscientists tell us that episodic memory is at once measurable and elusive of metrics — researchers can study the sequence of what we remember (like learning our ABC’s) but they struggle to discover how it feels to remember the alphabet.

Time after Will Castor’s AI is not waiting for cognitive neuroscience to catch up with a hacker’s race to design new codes, new systems, and new products for regenerating uberhuman biosystems. After all, AI Time presumes the speed of downloads to the Internet and programming APPs as if to emulate the speed of light.

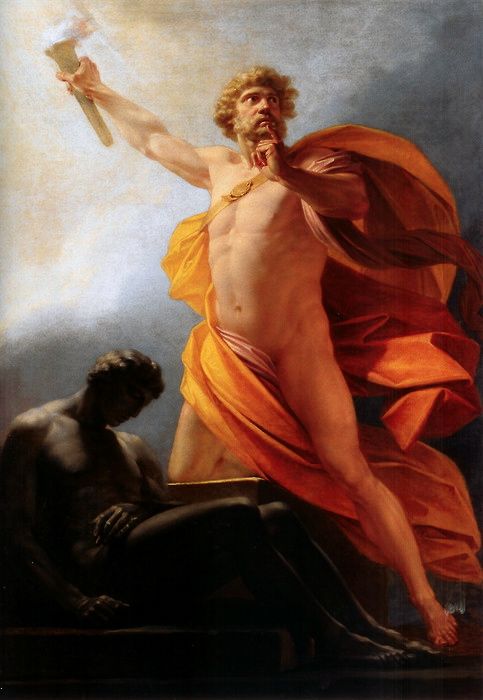

Before Einstein, Neuroscience, the Internet and Apps, Time was once thought of in mythic, primal terms of genesis. In Indian cosmology, Siva, the God of Time, dances on the back of mother earth, moving us through karmic cycles of birth, life, death and rebirth. In the ancient Greco-Roman cosmos, Time is born from Chronos the three headed serpent that gives us earth, sky and the underworld. Through the ages, Time / Chronos became associated with the cycle of seasons, assigning to the process of change in light and life, the name Father Time in contrast to quiet, deep Mother Earth, which seems to absorb the underworld into her womb.

Conceived as such, Father Time has given way to our current understanding of RAM and neural memory codes leaving Mother Earth to stand in for blood, bones and stem cells. Today as we couple with technology and look to Big Data for knowledge and insight, we lose sight of when, and how, we capitulate to a fundamental misperception: That we are one and the same with the technology we create. Blinded by the light and speed of computer gazing, we mistake ourselves for our creations. We forget difference and our humanity — even if coupled with technology. For the sake of a popular drama, Transcendence pushes on the consequences of this misperception by entertaining a bioethics war over regenerating biological tissue. Like I said, this is a flick with a nod to X-Men.

With computational neuroscience sitting at the center of this passion play, it is neurobiologist and bioethicist Max, the Castor’s closest friend and film’s narrator who reminds us that we are Time emergent and memories alone are not us. Memory may be coded for upload but it cannot fully account for the what and who we are as neuroplastic creatures with uncertain futures. Yes, we are more than just code. As the father of American psychology William James once wrote, we draw from a world of “blooming buzzing confusion,” perceptions enriched with a variety of associated thoughts, sensations and reactions. That piece of wisdom may be more than a century old, but even if our behaviors might fit a statistical profile for behavioral economics, we are reminded: statistical profiles are not Us.

Coda:

Looking back to the late 1990’s, the call for the human-machine interface was met by both excitement and trepidation by frontier technologists and skeptical intellectuals. In my own backyard, I curated a 2003 symposium at Art Center College of Design with NASA scientists and a world famous cyborg, STELARC to discuss: What kind of science and technologies would push the design futures forward and would our imagined futures require the inevitable coupling of human and technology? Now more than 10 years later with advances in the Cloud, wearable tech and neuro-marketing, students have no greater skills for managing their union with the Borg. To paraphrase the thinking of my business partner, Gaynor Strachan Chun, ‘the problem is not with technology, but the way people behave with technology.’

Future Forward? Let’s skill up with the brain in mind to face the behavioral challenges with Big Data.

M. A. Greenstein, Ph.D., Lifeboat Advisor — Neuroscience / Diplomacy / Futures; Founder / Chairman, The George Greenstein Institute (GGI); Founder / Chief Innovation Officer, SM+ART