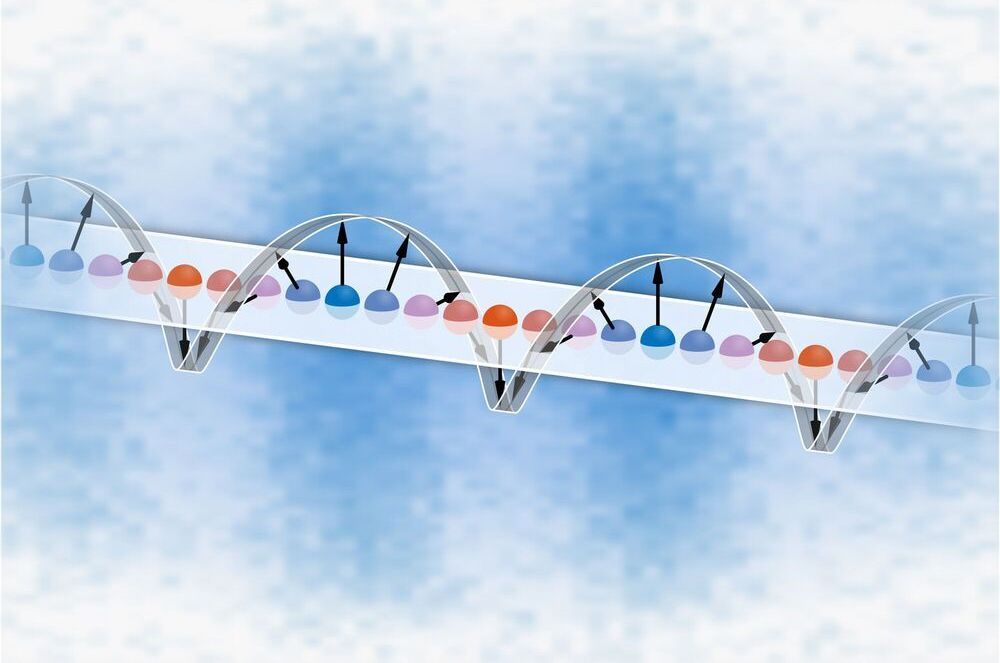

A new study illuminates surprising choreography among spinning atoms. In a paper appearing in the journal Nature, researchers from MIT and Harvard University reveal how magnetic forces at the quantum, atomic scale affect how atoms orient their spins.

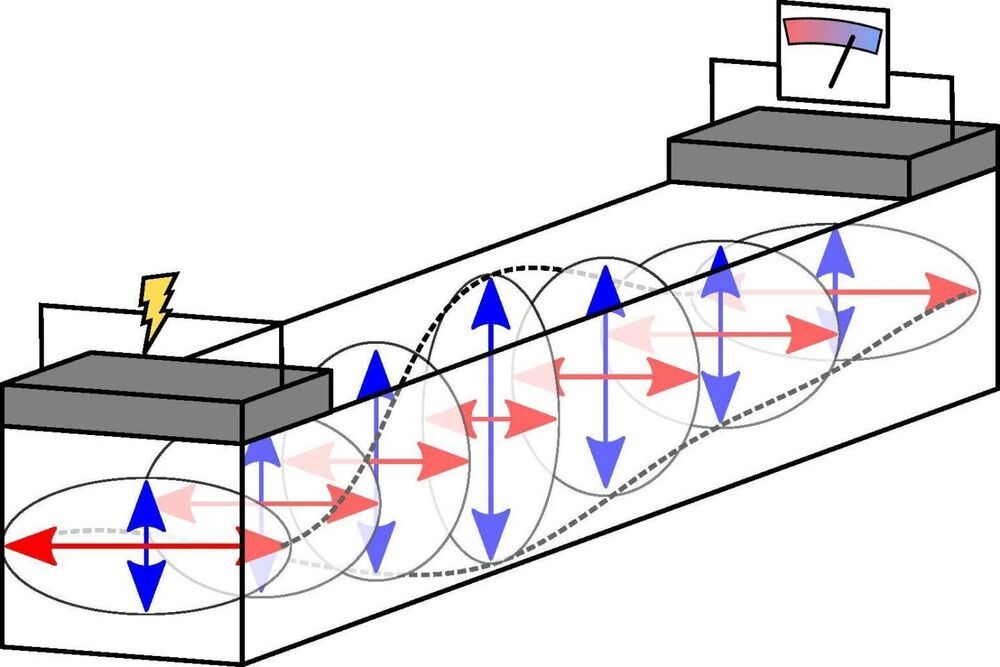

In experiments with ultracold lithium atoms, the researchers observed different ways in which the spins of the atoms evolve. Like tippy ballerinas pirouetting back to upright positions, the spinning atoms return to an equilibrium orientation in a way that depends on the magnetic forces between individual atoms. For example, the atoms can spin into equilibrium in an extremely fast, “ballistic” fashion or in a slower, more diffuse pattern.

The researchers found that these behaviors, which had not been observed until now, could be described mathematically by the Heisenberg model, a set of equations commonly used to predict magnetic behavior. Their results address the fundamental nature of magnetism, revealing a diversity of behavior in one of the simplest magnetic materials.