NASA researchers demonstrate the ability to fuse atoms inside room-temperature metals.

In 1979, CERN decided to convert the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) into a proton–antiproton collider. A technique called stochastic cooling was vital to the project’s success as it allowed enough antiprotons to be collected to make a beam.

The first proton–antiproton collisions were achieved just two years after the project was approved, and two experiments, UA1 and UA2, started to search the collision debris for signs of W and Z particles, carriers of the weak interaction between particles.

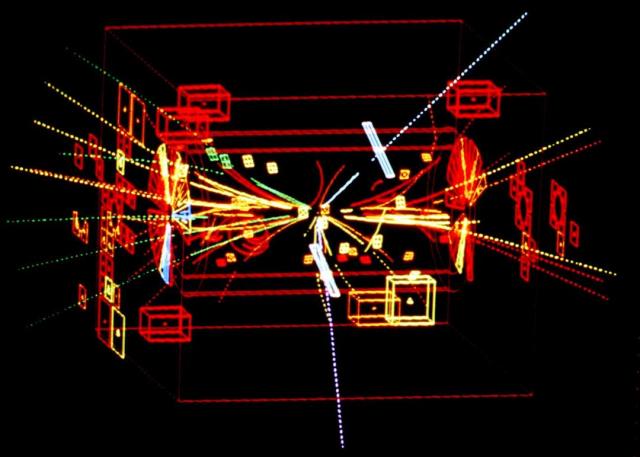

In 1983, CERN announced the discovery of the W and Z particles. The image above shows the first detection of a Z0 particle, as seen by the UA1 experiment on 30 April 1983. The Z0 itself decays very quickly so cannot be seen, but an electron–positron pair produced in the decay appear in blue. UA1 observed proton-antiproton collisions on the SPS between 1981 and 1993 to look for the Z and W bosons, which mediate the weak fundamental force.

Swarm intelligence (SI) is concerned with the collective behaviour that emerges from decentralised self-organising systems, whilst swarm robotics (SR) is an approach to the self-coordination of large numbers of simple robots which emerged as the application of SI to multi-robot systems. Given the increasing severity and frequency of occurrence of wildfires and the hazardous nature of fighting their propagation, the use of disposable inexpensive robots in place of humans is of special interest. This paper demonstrates the feasibility and potential of employing SR to fight fires autonomously, with a focus on the self-coordination mechanisms for the desired firefighting behaviour to emerge. Thus, an efficient physics-based model of fire propagation and a self-organisation algorithm for swarms of firefighting drones are developed and coupled, with the collaborative behaviour based on a particle swarm algorithm adapted to individuals operating within physical dynamic environments of high severity and frequency of change. Numerical experiments demonstrate that the proposed self-organising system is effective, scalable and fault-tolerant, comprising a promising approach to dealing with the suppression of wildfires – one of the world’s most pressing challenges of our time.

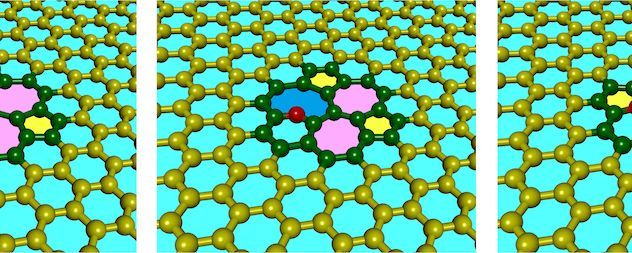

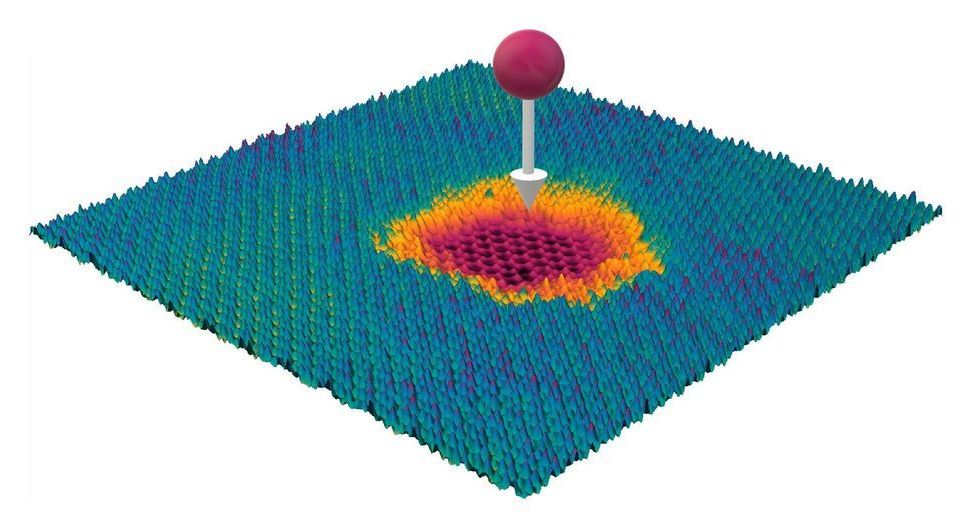

Graphene and other carbon materials are known to change their structure and even self-heal defects, but the processes involved in these atomic rearrangements often have high energy barriers and so shouldn’t occur under normal conditions. An international team of researchers in Korea, the UK, Japan, the US and France has now cleared up the mystery by showing that fast-moving carbon atoms catalyse many of the restructuring processes.

Graphene – a carbon sheet just one atomic layer thick – is an ideal system for studying defects because of its simple two-dimensional single-element structure. Until now, researchers typically explained the structural evolution of graphene defects via a mechanism known as a Stone-Thrower-Wales type bond rotation. This mechanism involves a change in the connectivity of atoms within the lattice, but it has a relatively large activation energy, making it “forbidden” without some form of assistance.

Using some of the best transmission electron microscopes available, researchers led by Alex Robertson of Oxford University and Kazu Suenaga of AIST Tsukuba found that so-called “mediator atoms” – carbon atoms that do not fit properly into the graphene lattice – act as catalysts to help bonds break and form. “The importance of these rapid, unseen ‘helpers’ has been previously underestimated because they move so fast and have been next-to-impossible to observe,” says co-team leader Christopher Ewels, a nanoscientist at the University of Nantes.

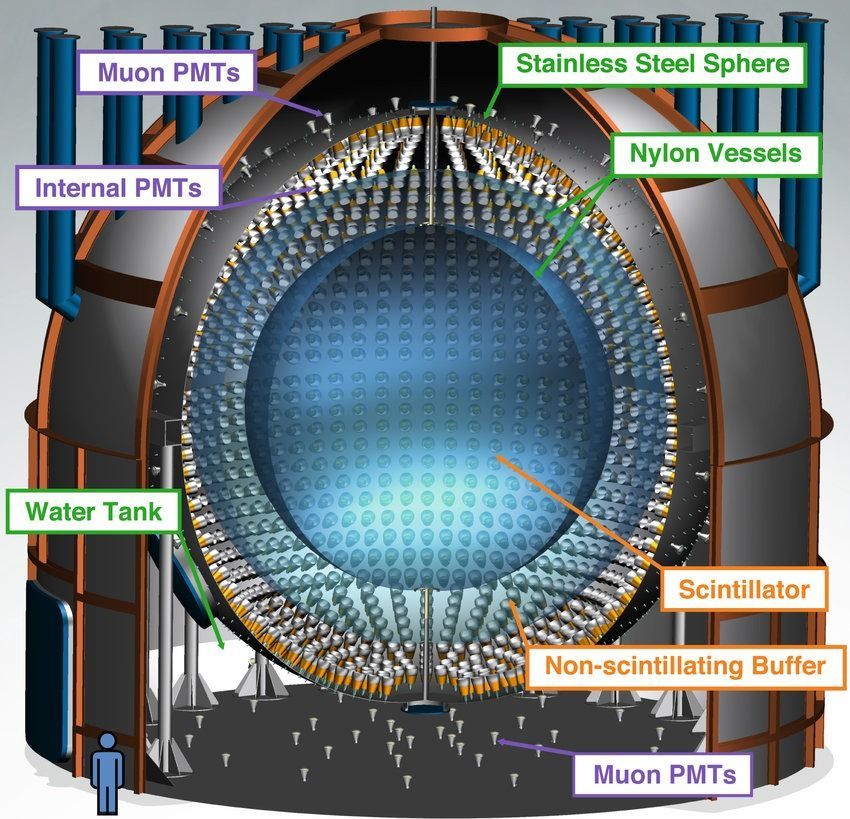

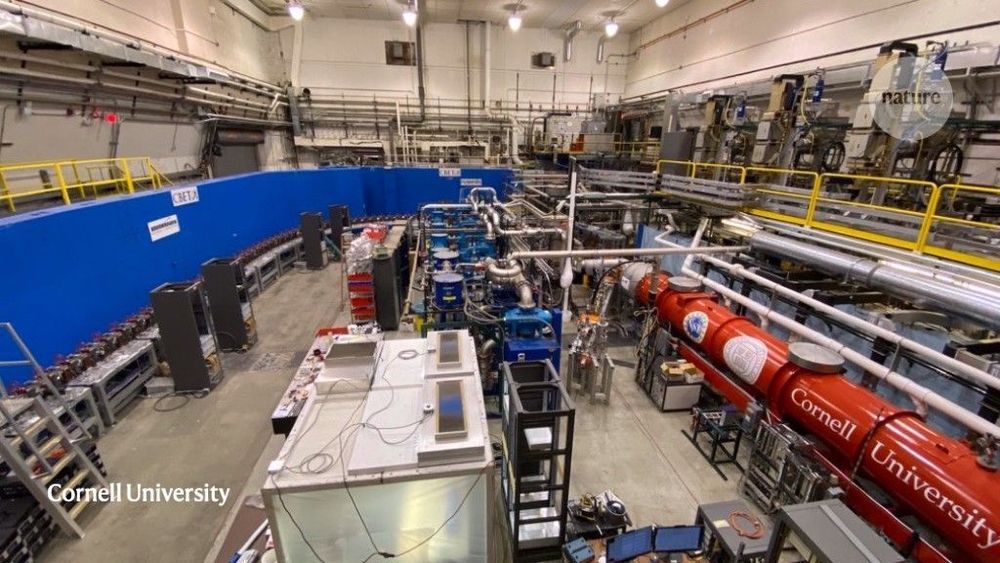

A team of researchers working on the Borexino project has announced that they have observed carbon/nitrogen/oxygen (CNO) fusion neutrinos from the sun for the first time. Co-spokesman for the group, Gioacchino Ranucci, a physicist at the University of Milan, announced the observation at this year’s virtual Neutrino 2020 conference.

The Borexino solar-neutrino project is an experiment being conducted underground at Gran Sasso National Laboratories in Italy—it has been in operation since 2007. Its mission is to observe neutrinos that are emitted from the sun via two kinds of fusion reactions. The laboratory is located beneath a kilometer of rock to filter noise. Inside, it houses a huge balloon made of nylon and filled with 278 tonnes of liquid hydrocarbons surrounded by water in a tank. The temperature inside the tank is kept constant by heat exchangers and a blanket cover. Photon sensors line the tank. Neutrinos can be observed when they collide with electrons inside the balloon, creating a tiny flash. The researchers determine the characteristics of the flashes, information that can be used to isolate their source.

Researchers on the project observed neutrinos from a type of fusion reaction called a proton-proton chain back in 2012—they are believed to represent 99 percent of the energy released from the sun. Spotting neutrinos produced during CNO reactions has presented more of a challenge because there are far fewer of them. In both cases, hydrogen is fused into helium. The elements that are part of the reaction are referred to as chains because they allow such reactions to proceed. In his presentation, Ranucci, claimed that the team had “…unraveled the two processes powering the sun.”

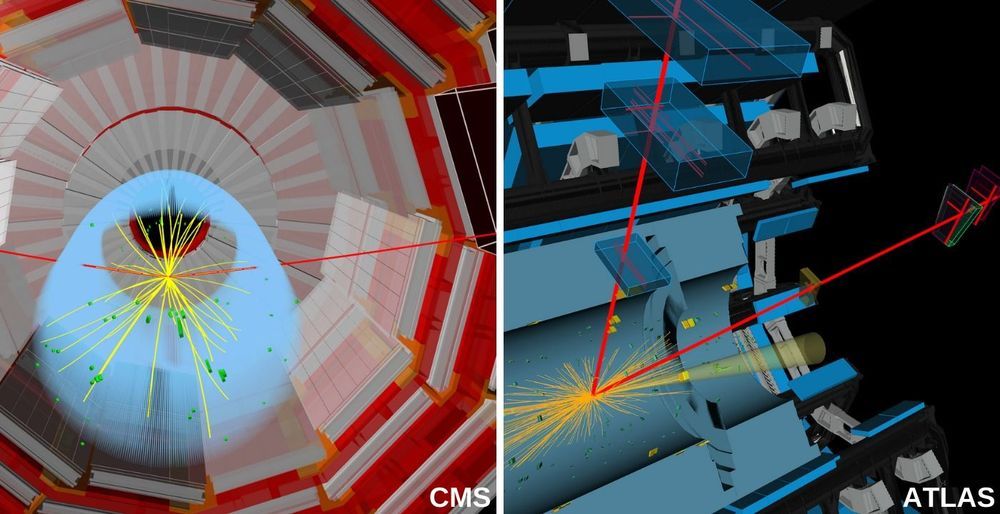

Geneva. At the 40th ICHEP conference, the ATLAS and CMS experiments announced new results which show that the Higgs boson decays into two muons. The muon is a heavier copy of the electron, one of the elementary particles that constitute the matter content of the Universe. While electrons are classified as a first-generation particle, muons belong to the second generation. The physics process of the Higgs boson decaying into muons is a rare phenomenon as only about one Higgs boson in 5000 decays into muons. These new results have pivotal importance for fundamental physics because they indicate for the first time that the Higgs boson interacts with second-generation elementary particles.

Physicists at CERN have been studying the Higgs boson since its discovery in 2012 in order to probe the properties of this very special particle. The Higgs boson, produced from proton collisions at the Large Hadron Collider, disintegrates – referred to as decay – almost instantaneously into other particles. One of the main methods of studying the Higgs boson’s properties is by analysing how it decays into the various fundamental particles and the rate of disintegration.

CMS achieved evidence of this decay with 3 sigma, which means that the chance of seeing the Higgs boson decaying into a muon pair from statistical fluctuation is less than one in 700. ATLAS’s two-sigma result means the chances are one in 40. The combination of both results would increase the significance well above 3 sigma and provides strong evidence for the Higgs boson decay to two muons.

Nobody can shoot a bullet through a banana in such a way that the skin is perforated but the banana remains intact. However, on the level of individual atomic layers, researchers at TU Wien (Vienna) have now achieved such a feat—they developed a nano-structuring method with which certain layers of material can be perforated extremely precisely and others left completely untouched, even though the projectile penetrates all layers. This is made possible with the help of highly charged ions. They can be used to selectively process the surfaces of novel 2-D material systems, for example, to anchor certain metals on them, which can then serve as catalysts. The new method has now been published in the journal ACS Nano.

New materials from ultra-thin layers

Materials that are composed of several ultra-thin layers are regarded as an exciting new field of materials research. The high-performance material graphene, which consists of only a single layer of carbon atoms, has been used in many new thin-film materials with promising new properties.

Researchers devise an on-off system that allows high-fidelity operations and interconnection between processors.

MIT researchers have introduced a quantum computing architecture that can perform low-error quantum computations while also rapidly sharing quantum information between processors. The work represents a key advance toward a complete quantum computing platform.

Previous to this discovery, small-scale quantum processors have successfully performed tasks at a rate exponentially faster than that of classical computers. However, it has been difficult to controllably communicate quantum information between distant parts of a processor. In classical computers, wired interconnects are used to route information back and forth throughout a processor during the course of a computation. In a quantum computer, however, the information itself is quantum mechanical and fragile, requiring fundamentally new strategies to simultaneously process and communicate quantum information on a chip.