If you replace classical bits with qubits, though, you go back to only needing one per spin in the system, because all the quantum stuff comes along for free. You don&s;t need extra bits to track the superposition, because the qubits themselves can be in superposition states. And you don&s;t need extra bits to track the entanglement, because the qubits themselves can be entangled with other qubits. A not-too-big quantum computer— again, 50–100 qubits— can efficiently solve problems that are simply impossible for a classical computer.

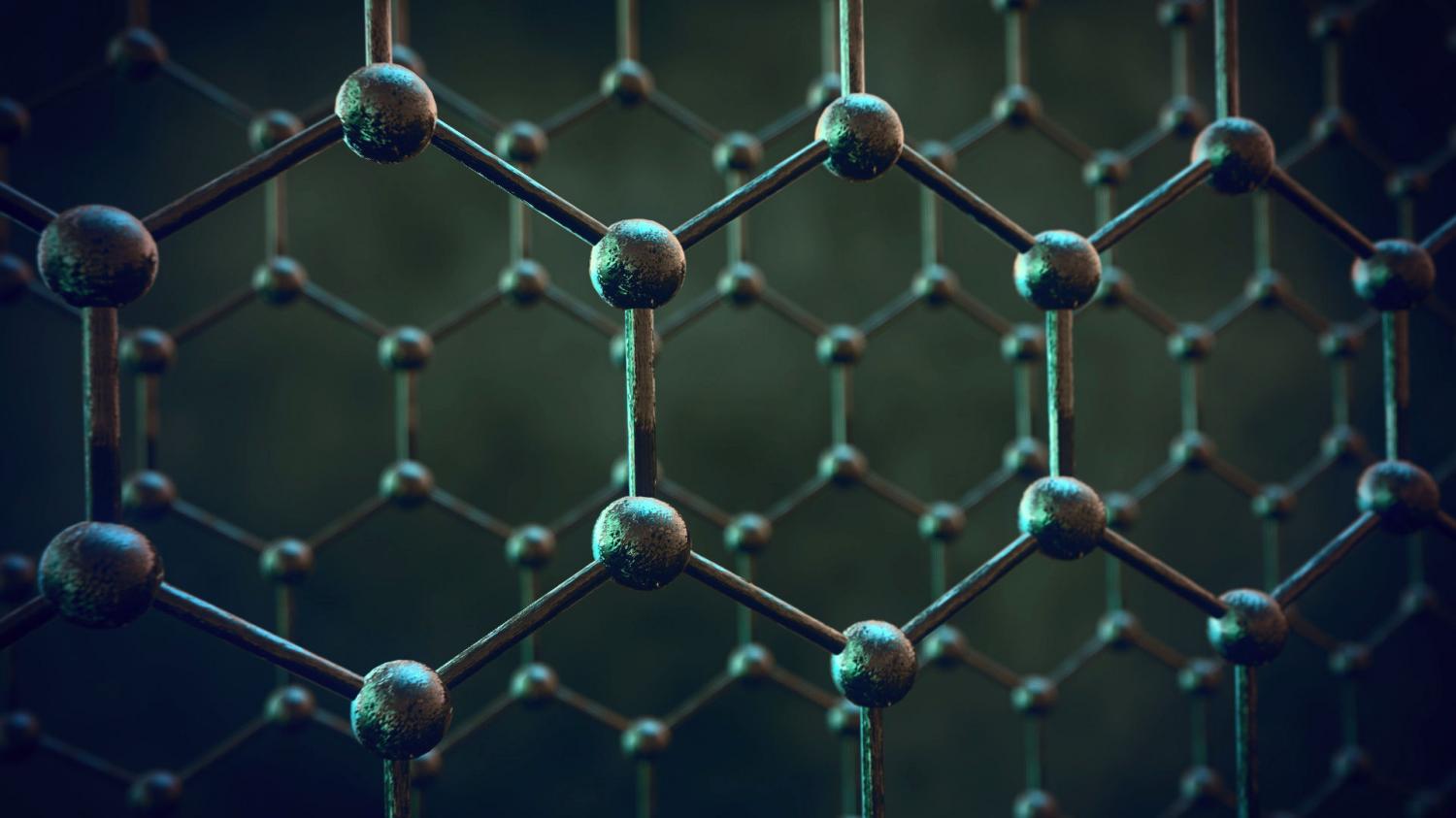

These sorts of problems pop up in useful contexts, such as the study of magnetic materials, whose magnetic nature comes from adding together the quantum spins of lots of particles, or some types of superconductors. As a general matter, any time you&s;re trying to find the state of a large quantum system, the computational overhead needed to do it will be much less if you can map it onto a system of qubits than if you&s;re stuck using a classical computer.

So, there&s;s your view-from-30,000-feet look at what quantum computing is, and what it&s;s good for. A quantum computer is a device that exploits wave nature, superposition, and entanglement to do calculations involving collective mathematical properties or the simulation of quantum systems more efficiently than you can do with any classical computer. That&s;s why these are interesting systems to study, and why heavy hitters like Google, Microsoft, and IBM are starting to invest heavily in the field.

Read more