For decades, researchers have been exploring ways to replicate on Earth the physical process of fusion that occurs naturally in the sun and other stars. Confined by its own strong gravitational field, the sun’s burning plasma is a sphere of fusing particles, producing the heat and light that makes life possible on earth. But the path to a creating a commercially viable fusion reactor, which would provide the world with a virtually endless source of clean energy, is filled with challenges.

Researchers have focused on the tokamak, a device that heats and confines turbulent plasma fuel in a donut-shaped chamber long enough to create fusion. Because plasma responds to magnetic fields, the torus is wrapped in magnets, which guide the fusing plasma particles around the toroidal chamber and away from the walls. Tokamaks have been able to sustain these reactions only in short pulses. To be a practical source of energy, they will need to operate in a steady state, around the clock.

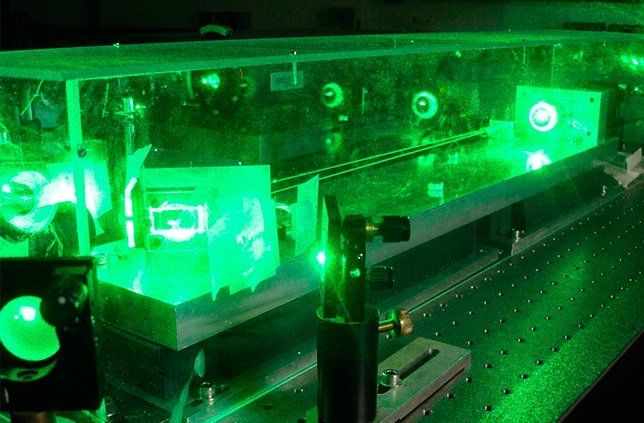

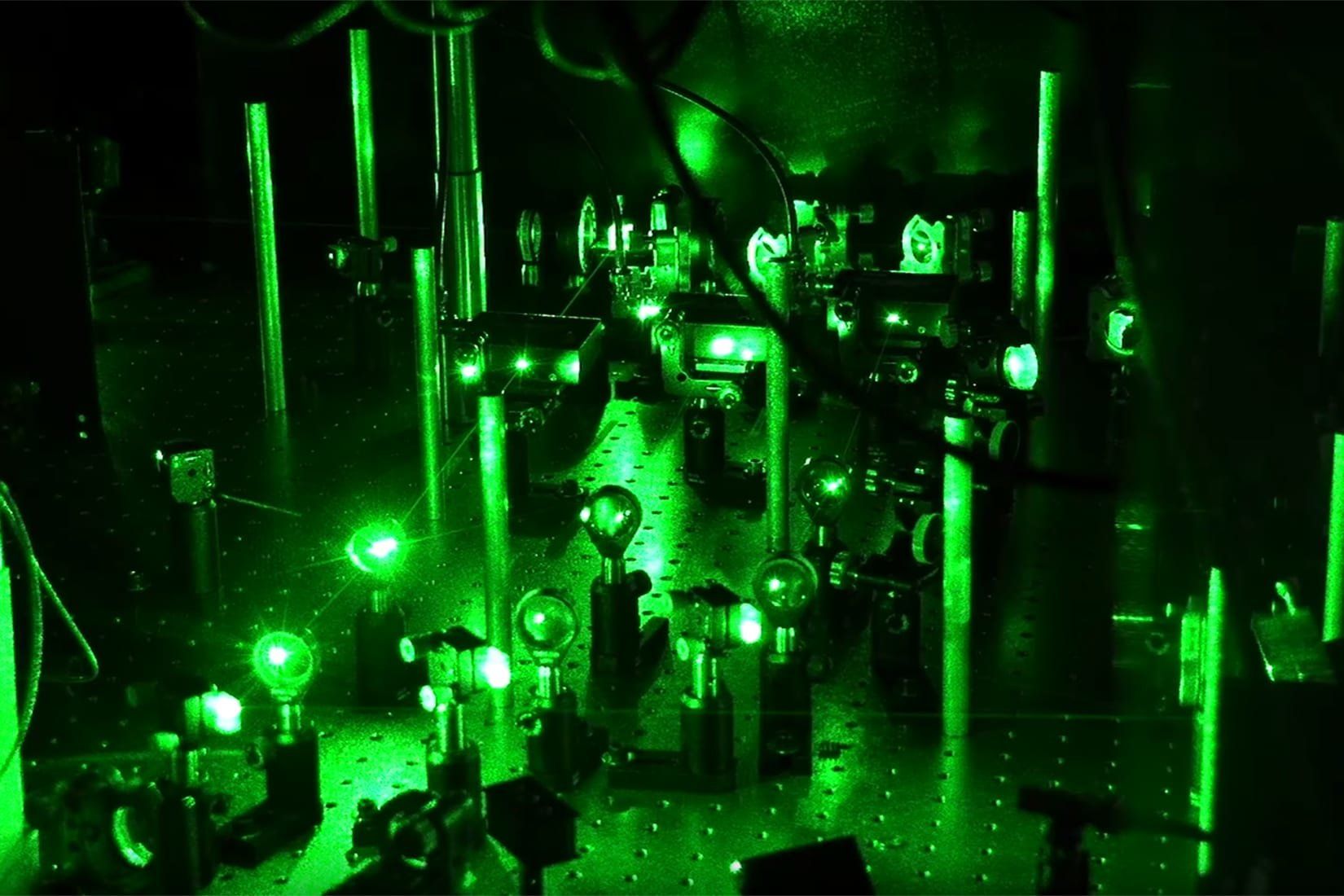

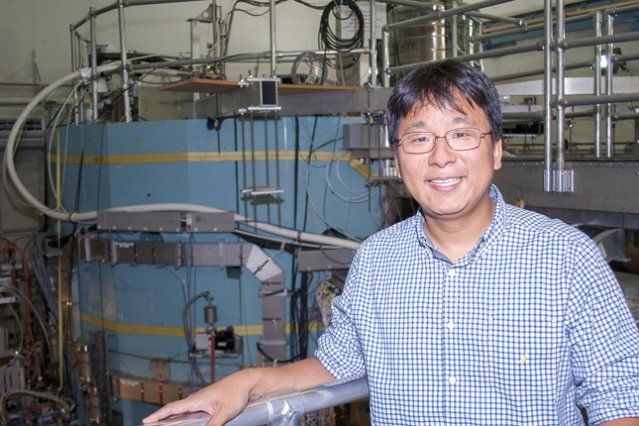

Researchers at MIT’s Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC) have now demonstrated how microwaves can be used to overcome barriers to steady-state tokamak operation. In experiments performed on MIT’s Alcator C-Mod tokamak before it ended operation in September 2016, research scientist Seung Gyou Baek and his colleagues studied a method of driving current to heat the plasma called Lower Hybrid Current Drive (LHCD). The technique generates plasma current by launching microwaves into the tokamak, pushing the electrons in one direction—a prerequisite for steady-state operation.

Read more