Credit where credit is due: Evolution has invented a galaxy of clever adaptations, from fish that swim up sea cucumber butts and eat their gonads, to parasites that mind-control their hosts in wildly complex ways. But it’s never dreamed up ion propulsion, a fantastical new way to power robots by accelerating ions instead of burning fuel or spinning rotors. The technology is in very early development, but it could lead to machines that fly like nothing that’s come before them.

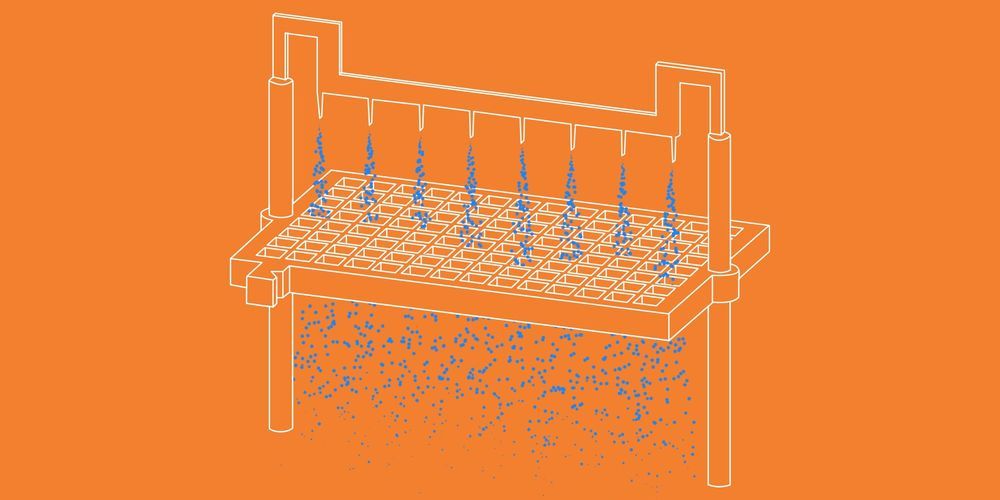

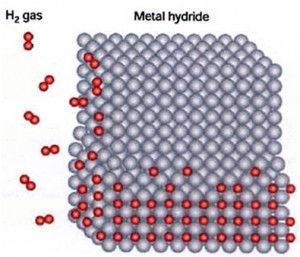

You may have heard of ion propulsion in the context of spacecraft, but this application is a bit different. Most solar-powered ion spacecraft bombard xenon atoms with electrons, producing positively charged xenon ions that then rush toward a negatively charged grid, which accelerates the ions into space. The resulting thrust is piddling compared to traditional engines, and that’s OK—the spacecraft is floating through the vacuum of space, so the shower of ions accelerate the aircraft bit by bit.

You’ve read your last complimentary article this month. To read the full article, SUBSCRIBE NOW. If you’re already a subscriber, please sign in and and verify your subscription.