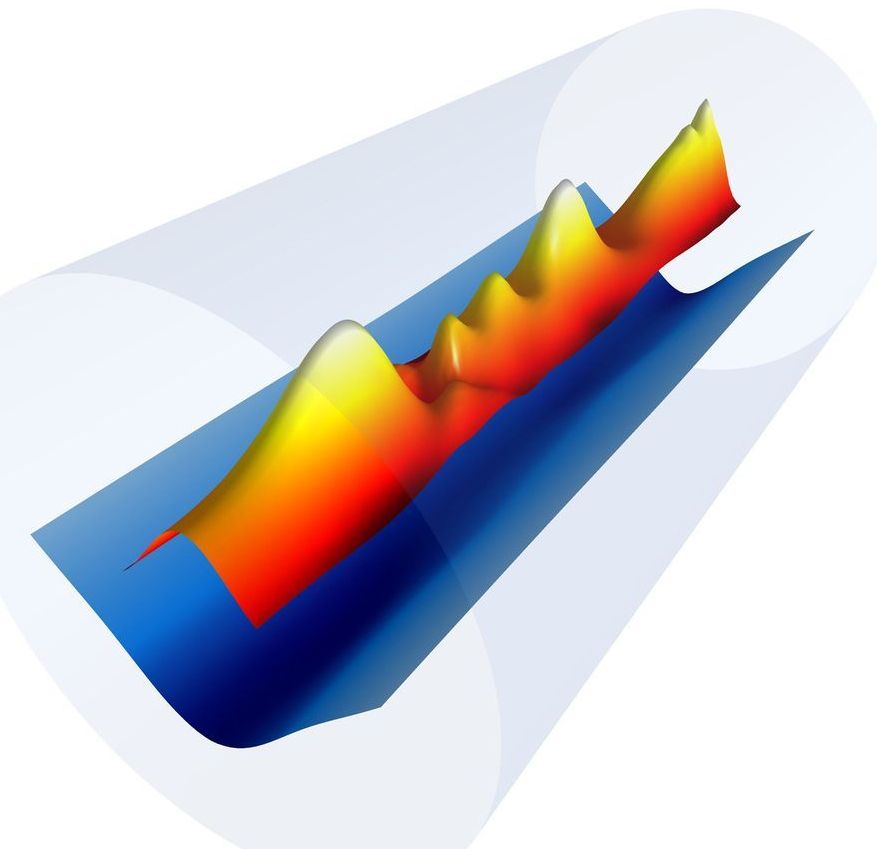

When a guitar string is plucked, it vibrates as any vibrating object would, rising and falling like a wave, as the laws of classical physics predict. But under the laws of quantum mechanics, which describe the way physics works at the atomic scale, vibrations should behave not only as waves, but also as particles. The same guitar string, when observed at a quantum level, should vibrate as individual units of energy known as phonons.

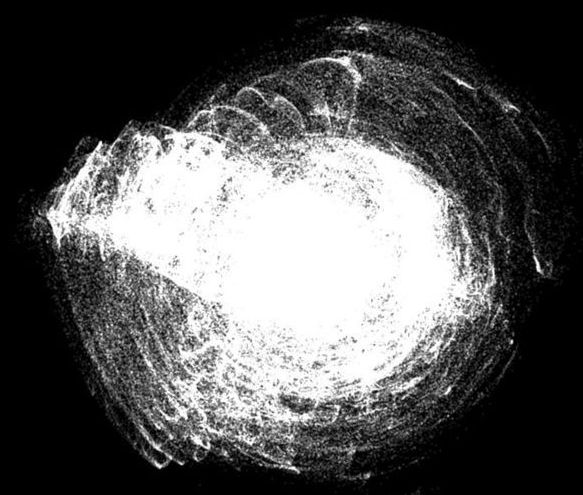

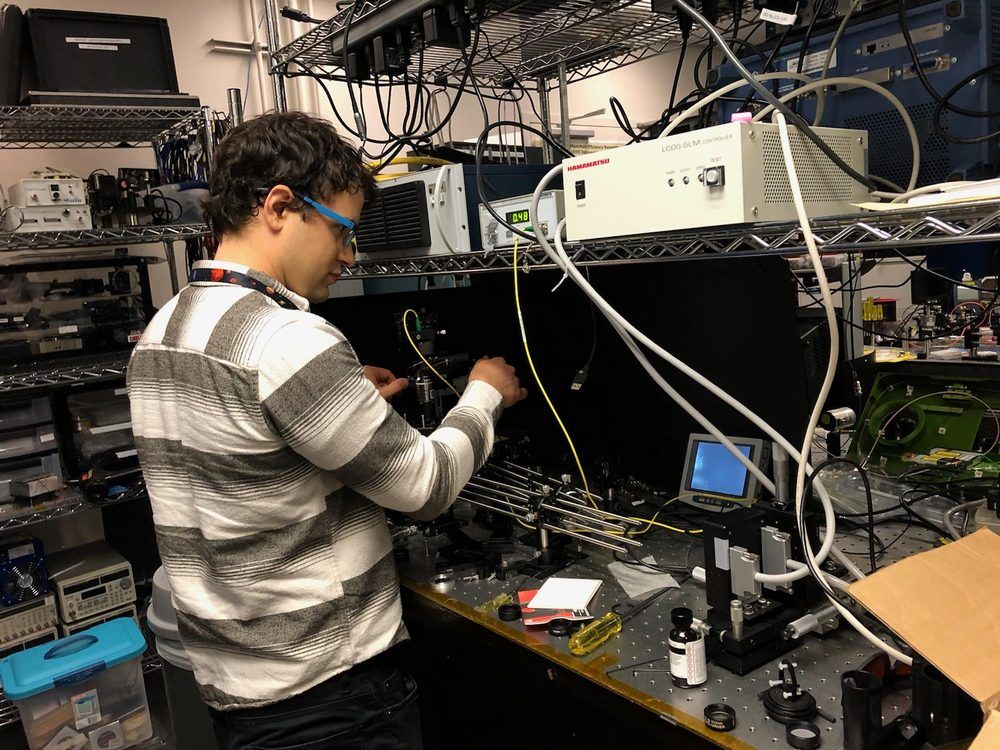

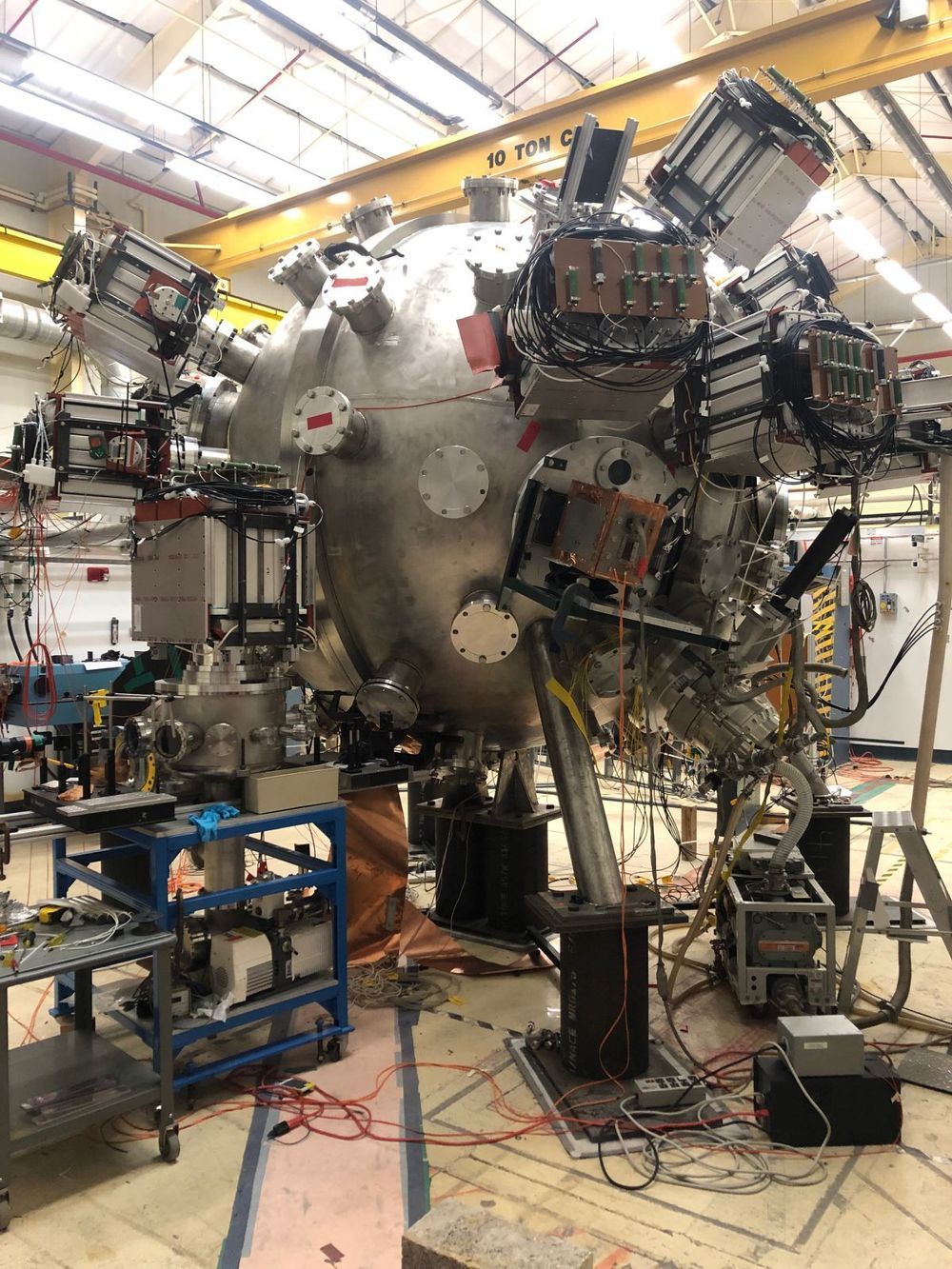

Now scientists at MIT and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology have for the first time created and observed a single phonon in a common material at room temperature.

Until now, single phonons have only been observed at ultracold temperatures and in precisely engineered, microscopic materials that researchers must probe in a vacuum. In contrast, the team has created and observed single phonons in a piece of diamond sitting in open air at room temperature. The results, the researchers write in a paper published today in Physical Review X, “bring quantum behavior closer to our daily life.”