CERN’s colossal complex of accelerators is in the midst of a two-year shutdown for upgrade work. But that doesn’t mean all experiments at the Laboratory have ceased to operate. The CLOUD experiment, for example, has just started a data run that will last until the end of November.

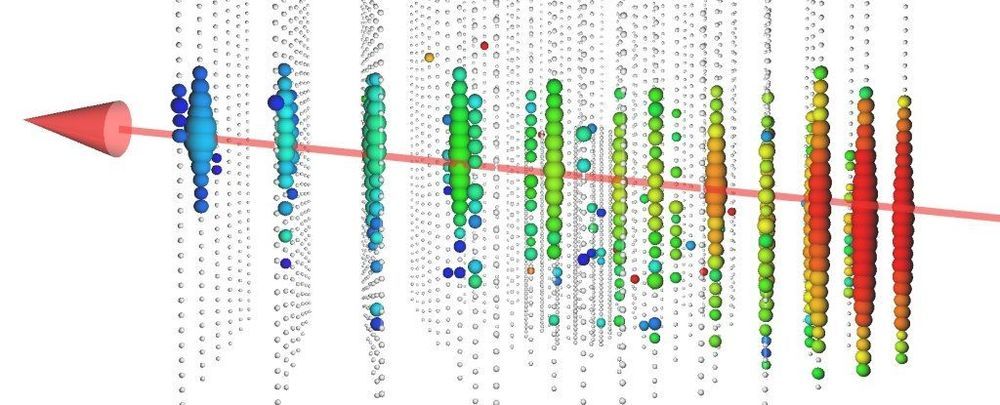

The CLOUD experiment studies how ions produced by high-energy particles called cosmic rays affect aerosol particles, clouds and the climate. It uses a special cloud chamber and a beam of particles from the Proton Synchrotron to provide an artificial source of cosmic rays. For this run, however, the cosmic rays are instead natural high-energy particles from cosmic objects such as exploding stars.

“Cosmic rays, whether natural or artificial, leave a trail of ions in the chamber,” explains CLOUD spokesperson Jasper Kirkby, “but the Proton Synchrotron provides cosmic rays that can be adjusted over the full range of ionisation rates occurring in the troposphere, which comprises the lowest ten kilometres of the atmosphere. That said, we can also make progress with the steady flux of natural cosmic rays that make it into our chamber, and this is what we’re doing now.”