Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University, host of Ask a Spaceman and Space Radio, and author of “Your Place in the Universe.” Sutter contributed this article to Space.com’s Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

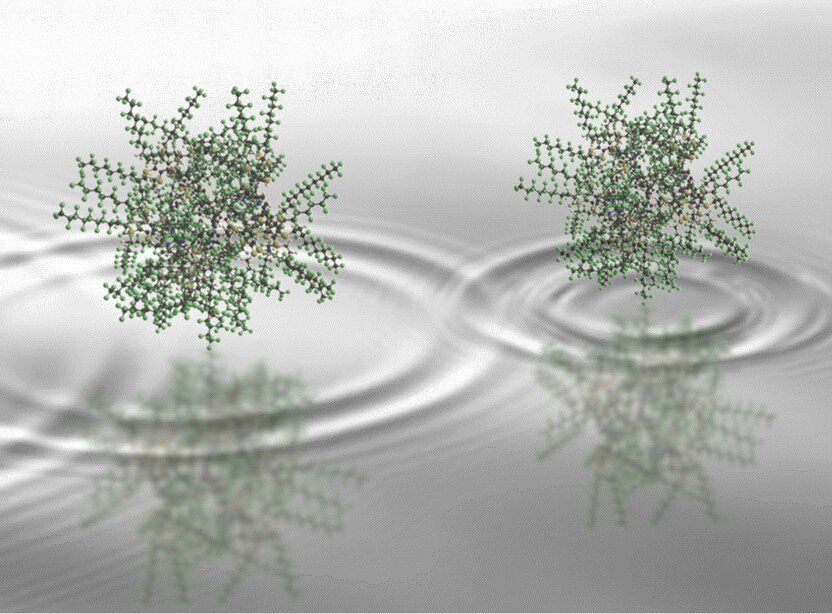

Is it a wave, or is it a particle? This seems like a very simple question. Waves are very distinct phenomena in our universe, as are particles. And we have different sets of mathematics to describe each of them. So, if we want to go about describing the entire universe, this appears to be a very handy classification scheme — except when it isn’t. And it isn’t in one of the most important aspects of our universe: the subatomic world.

When it comes to things like photons and electrons, the answer to the question “Do they behave like waves or particles?” is … yes.