Data from ESA’s Cluster mission has provided a recording of the eerie “song” that Earth sings when it is hit by a solar storm.

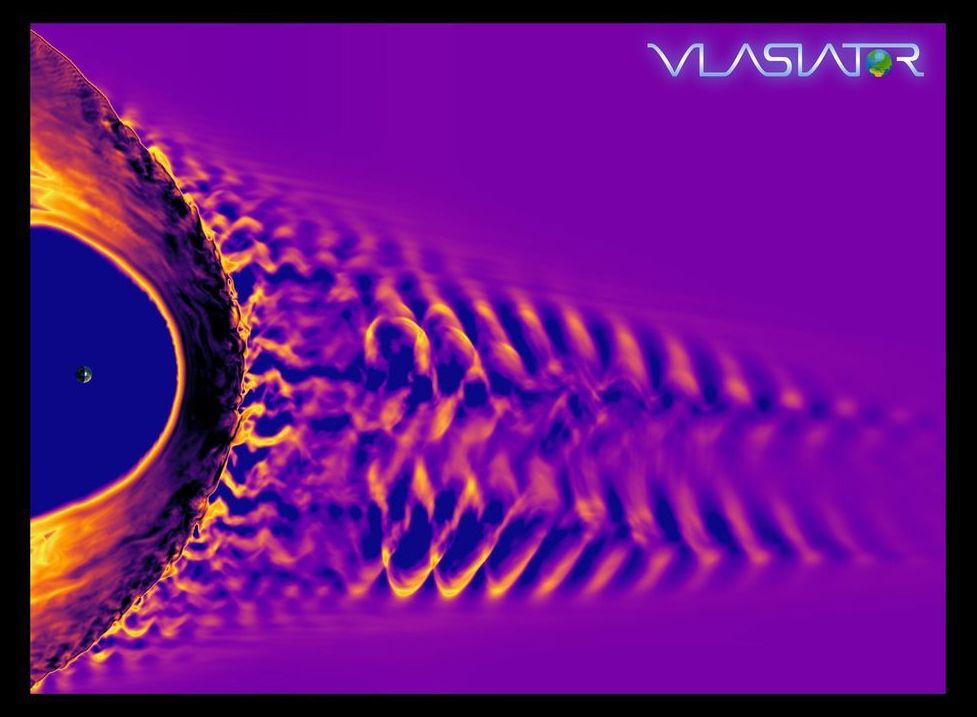

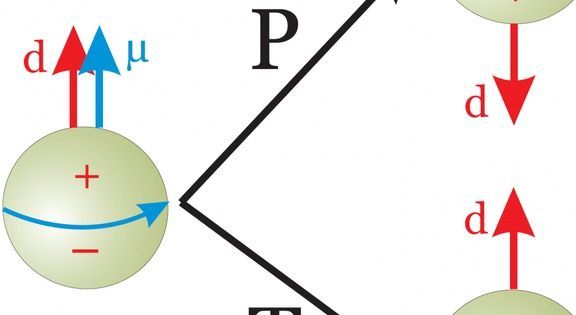

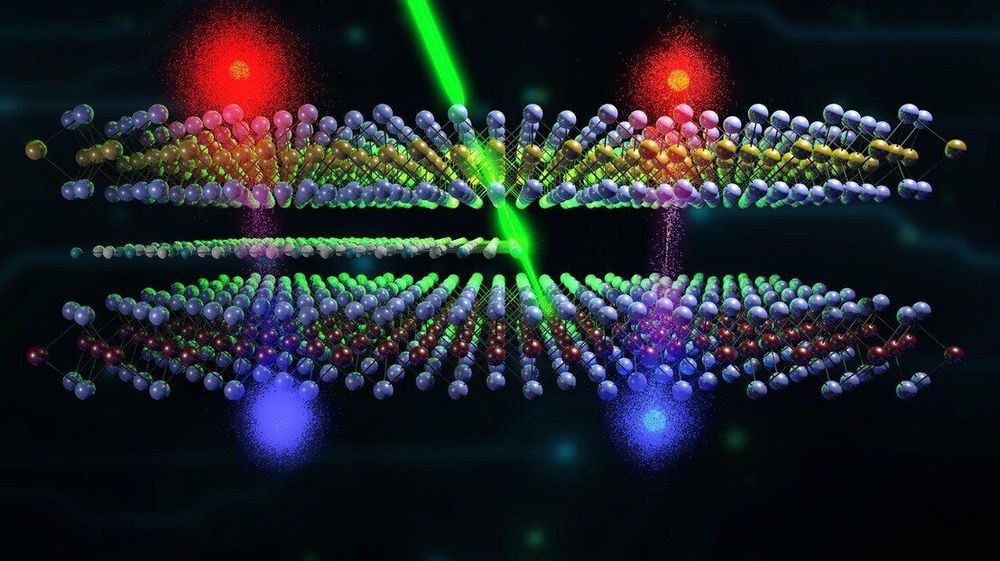

The song comes from waves that are generated in the Earth’s magnetic field by the collision of the storm. The storm itself is the eruption of electrically charged particles from the sun’s atmosphere.

A team led by Lucile Turc, a former ESA research fellow who is now based at the University of Helsinki, Finland, made the discovery after analyzing data from the Cluster Science Archive. The archive provides access to all data obtained during Cluster’s ongoing mission over almost two decades.