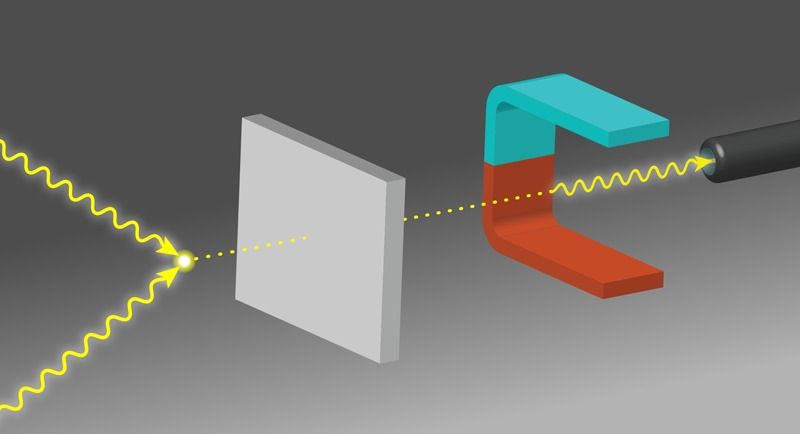

Here’s a new chapter in the story of the miniaturization of machines: researchers in a laboratory in Singapore have shown that a single atom can function as either an engine or a fridge. Such a device could be engineered into future computers and fuel cells to control energy flows.” Think about how your computer or laptop has a lot of things inside it that heat up. Today you cool that with a fan that blows air. In nanomachines or quantum computers, small devices that do cooling could be something useful,” says Dario Poletti from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD).

This work gives new insight into the mechanics of such devices. The work is a collaboration involving researchers at the Centre for Quantum Technologies (CQT) and Department of Physics at the National University of Singapore (NUS), SUTD and at the University of Augsburg in Germany. The results were published in the peer-reviewed journal npj Quantum Information on 1 May.

Engines and refrigerators are both machines described by thermodynamics, a branch of science that tells us how energy moves within a system and how we can extract useful work. A classical engine turns energy into useful work. A refrigerator does work to transfer heat, reducing the local temperature. They are, in some sense, opposites.