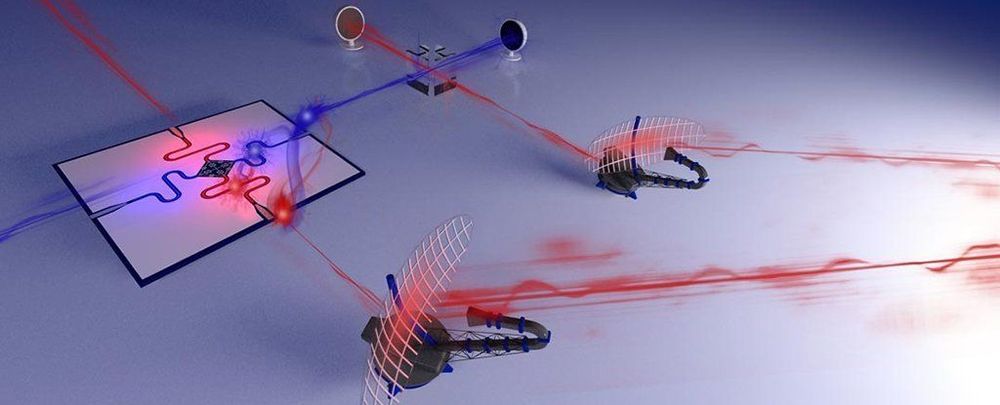

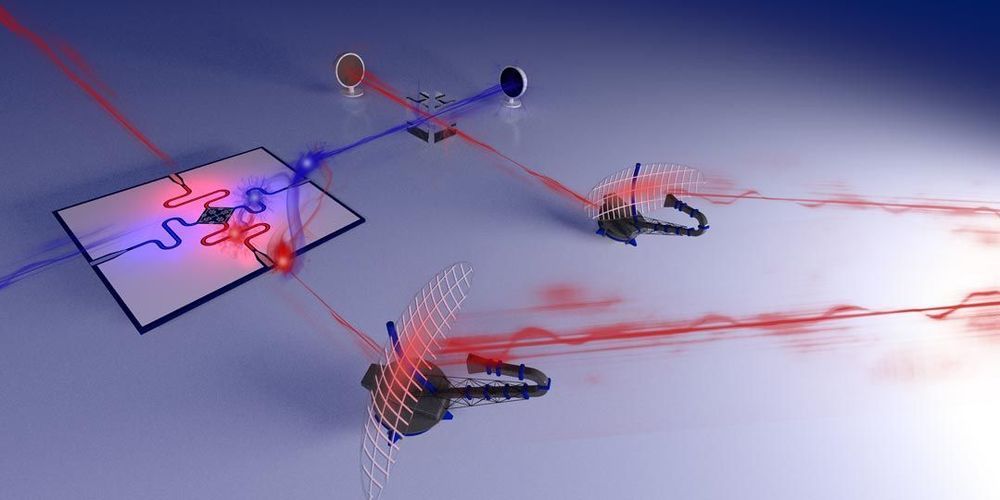

Quantum entanglement is a process by which microscopic objects like electrons or atoms lose their individuality to become better coordinated with each other. Entanglement is at the heart of quantum technologies that promise large advances in computing, communications and sensing, for example, detecting gravitational waves.

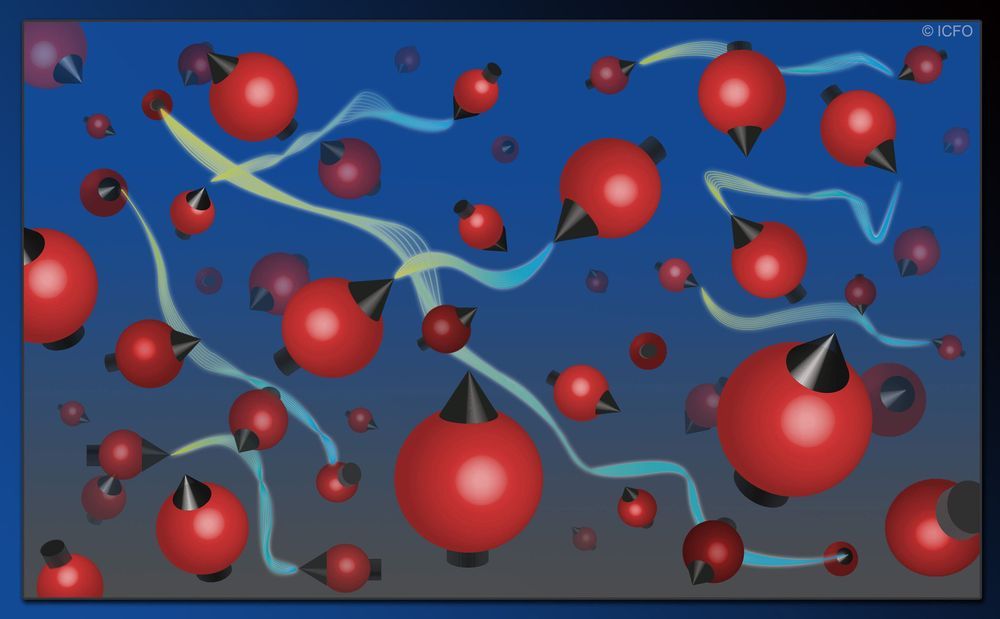

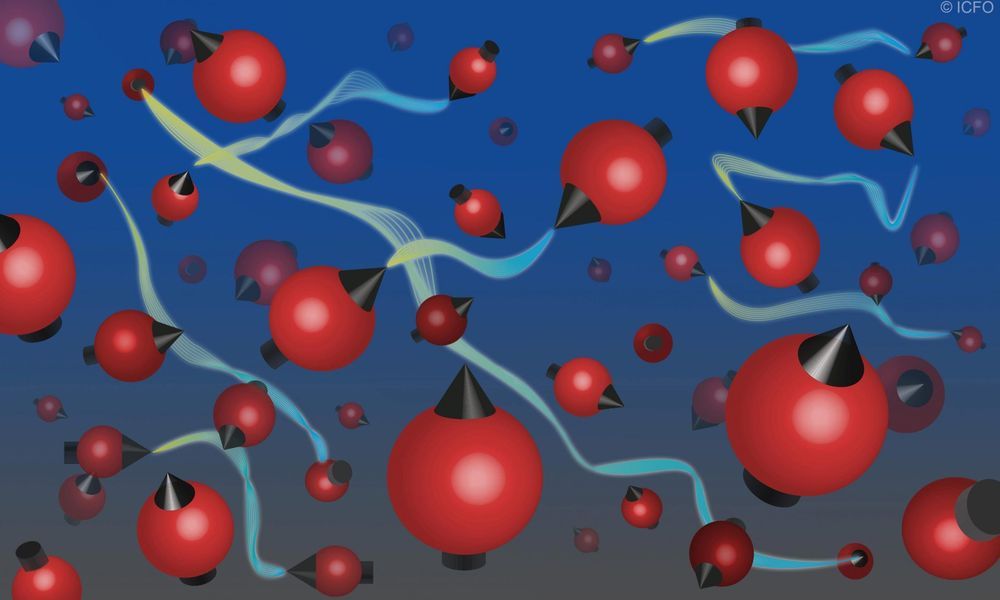

Entangled states are famously fragile: In most cases, even a tiny disturbance will undo the entanglement. For this reason, current quantum technologies take great pains to isolate the microscopic systems they work with, and typically operate at temperatures close to absolute zero. The ICFO team, in contrast, heated a collection of atoms to 450 Kelvin in a recent experiment, millions of times hotter than most atoms used for quantum technology. Moreover, the individual atoms were anything but isolated; they collided with each other every few microseconds, and each collision set their electrons spinning in random directions.

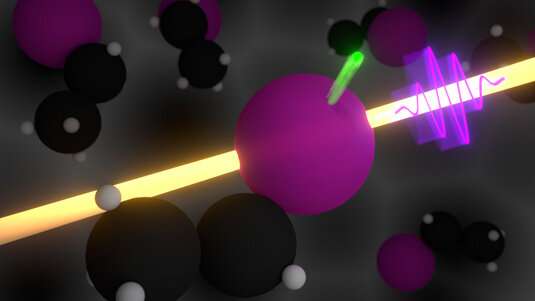

The researchers used a laser to monitor the magnetization of this hot, chaotic gas. The magnetization is caused by the spinning electrons in the atoms, and provides a way to study the effect of the collisions and to detect entanglement. What the researchers observed was an enormous number of entangled atoms—about 100 times more than ever before observed. They also saw that the entanglement is non-local—it involves atoms that are not close to each other. Between any two entangled atoms there are thousands of other atoms, many of which are entangled with still other atoms, in a giant, hot and messy entangled state.