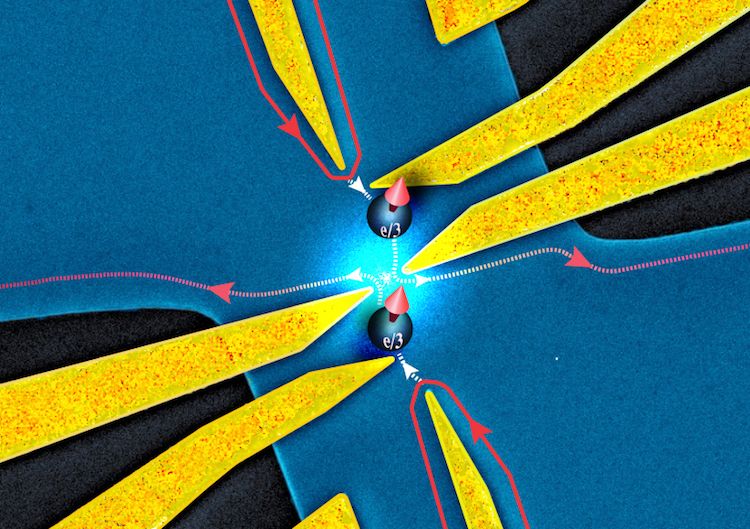

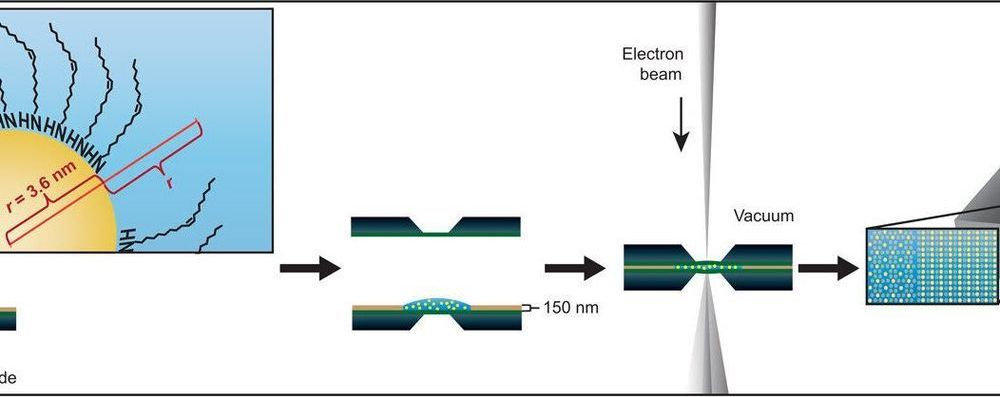

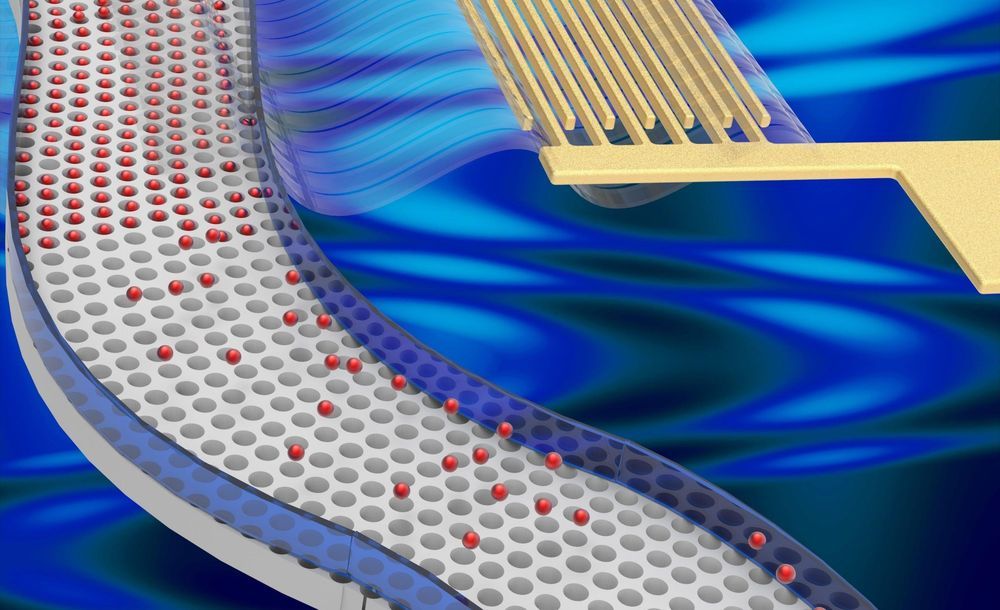

Anyons – the particle-like collective excitations that can exist in some 2D materials – tend to bunch together in a two-dimensional conductor. This behaviour, which has now been observed by physicists at the Laboratory of Physics of the ENS (LPENS) and the Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnologies (C2N) in Paris, France, is completely different to that of electrons, and experimental evidence for it is important both for fundamental physics and for the potential future development of devices based on these exotic quasiparticles.

The everyday three-dimensional world contains two types of elementary particles: fermions and bosons. Fermions, such as electrons, obey the Pauli exclusion principle, meaning that no two fermions can ever occupy the same quantum state. This tendency to flee from each other is at the heart of a wide range of phenomena, including the electronic structure of atoms, the stability of neutron stars and the difference between metals (which conduct electric current) and insulators (which don’t). Bosons such as photons, on the other hand, tend to bunch together – a gregarious behaviour that gives rise to superfluid and superconducting behaviours when many bosons exist in the same quantum state.

Within the framework of quantum mechanics, fermions also differ from bosons in that they have antisymmetric wavefunctions – meaning that a minus sign (that is, a phase φ equal to π) is introduced whenever two fermions are exchanged. Bosons, in contrast, have symmetric wavefunctions that remain the same when two bosons are exchanged (φ=0).