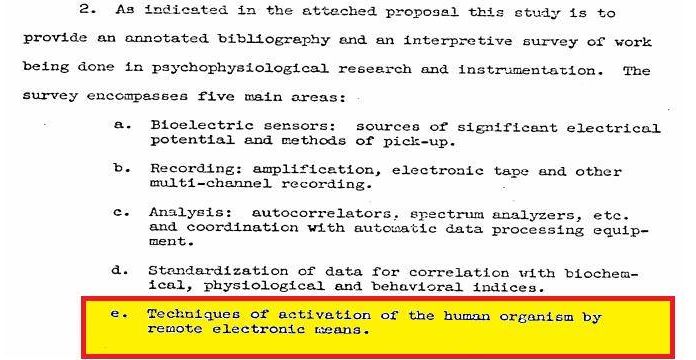

As mentioned by H. Girard in the article at the link http://www.i-sis.org.uk/BW.php&h=AT2S6vfN4BKfFUss7oiAPJJSeWk3JhP1PjA1zKrg6fQ3fKzkekIvqxdmvsNBoBqy_7daZU_isSxygcy32ntUs9MchsVE7rnSwd5AcPRugw1bixDwHbyryEh7Ry23VeQFyNsitStG0dUhk5_tj3bB9O2inoSL_iHt0LMs0OBvrPDKNbM67wXNVie3w2jb-y0arw, in 1960, the CIA approved a proposal for a very sophisticated electroencephalography instrument that could be used to interpret brain activity, decipher thought content and obtain information whether a person would wish to disclose it or not. They also added to this a bibliography search with five objectives, the fifth termed Techniques for Activating the Human Organism by Remote Electronic Means . This study became known later as MKULTRA subproject 119, with MKULTRA being the CIA s mind control program.

Documents that are related to MKULTRA were obtained by a FOIA request by John Marks who conducted research for his book “The Search For The Manchurian Candidate — The CIA and Mind Control, The Secret History of the Behavioral Sciences” (1979) published by W. Norton — paperback 1991, ISBN 0−393−30794−8. The author donated the documents to the National Security Archive of the George Washington University (http//www.seas.gwu.edu/nsarchive.html).