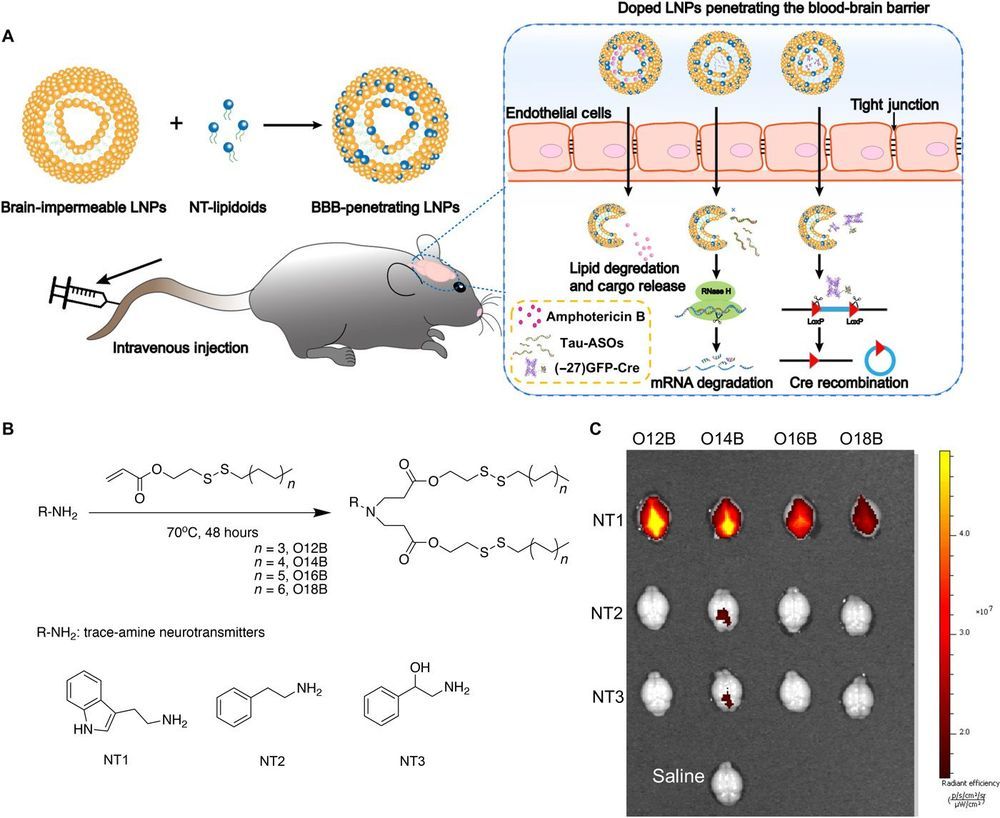

Summary: Tufts researchers have developed neurotransmitter-lipid hybrids that help transport therapeutic drugs and gene editing proteins across the blood-brain barrier in mice.

Source: Tufts University

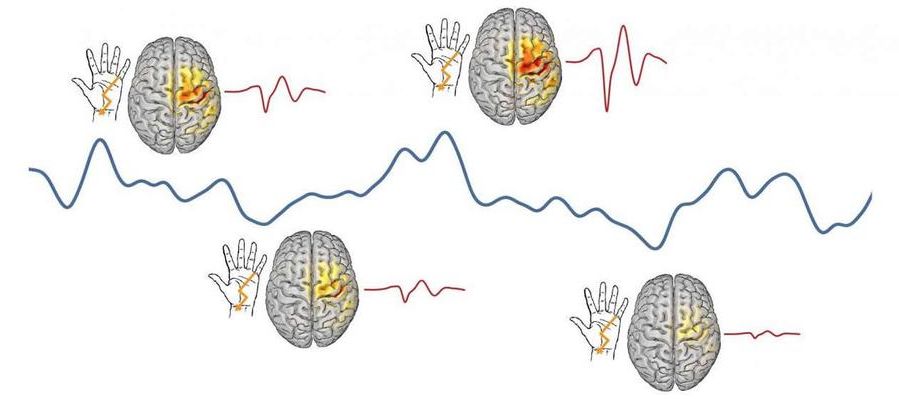

Biomedical engineers at the Tufts University School of Engineering have developed tiny lipid-based nanoparticles that incorporate neurotranmitters to help carry drugs, large molecules, and even gene editing proteins across the blood-brain barrier and into the brain in mice. The innovation, published today in Science Advances, could overcome many of the current limitations encountered in delivering therapeutics into the central nervous system, and opens up the possibility of using a wide range of therapeutics that would otherwise not have access to the brain.