Circa 2016 o,.o.

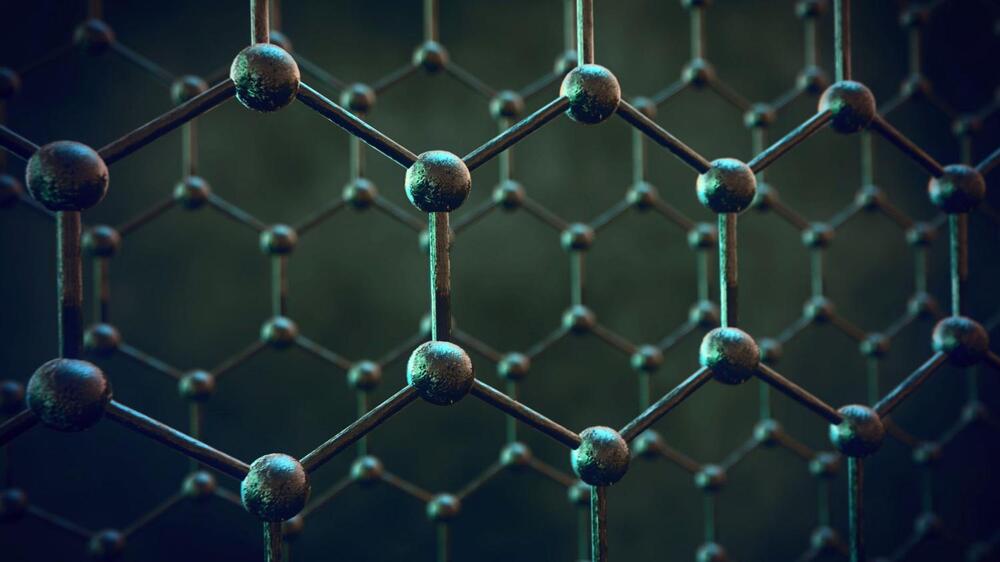

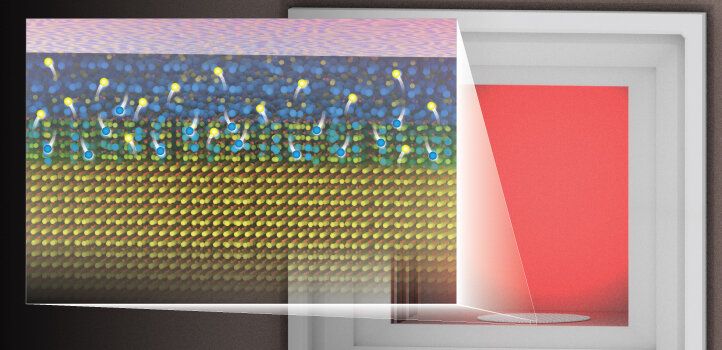

Titanium is the leading material for artificial knee and hip joints because it’s strong, wear-resistant and nontoxic, but an unexpected discovery by Rice University physicists shows that the gold standard for artificial joints can be improved with the addition of some actual gold.

“It is about 3–4 times harder than most steels,” said Emilia Morosan, the lead scientist on a new study in Science Advances that describes the properties of a 3-to-1 mixture of titanium and gold with a specific atomic structure that imparts hardness. “It’s four times harder than pure titanium, which is what’s currently being used in most dental implants and replacement joints.”

Morosan, a physicist who specializes in the design and synthesis of compounds with exotic electronic and magnetic properties, said the new study is “a first for me in a number of ways. This compound is not difficult to make, and it’s not a new material.”