3D printing has opened up a completely new range of possibilities. One example is the production of novel turbine buckets. However, the 3D printing process often induces internal stress in the components, which can, in the worst case, lead to cracks. Now a research team has succeeded in using neutrons from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) research neutron source for non-destructive detection of this internal stress—a key achievement for the improvement of the production processes.

Gas turbine buckets have to withstand extreme conditions: Under high pressure and at high temperatures they are exposed to tremendous centrifugal forces. In order to further maximize energy yields, the buckets have to hold up to temperatures which are actually higher than the melting point of the material. This is made possible using hollow turbine buckets which are air-cooled from the inside.

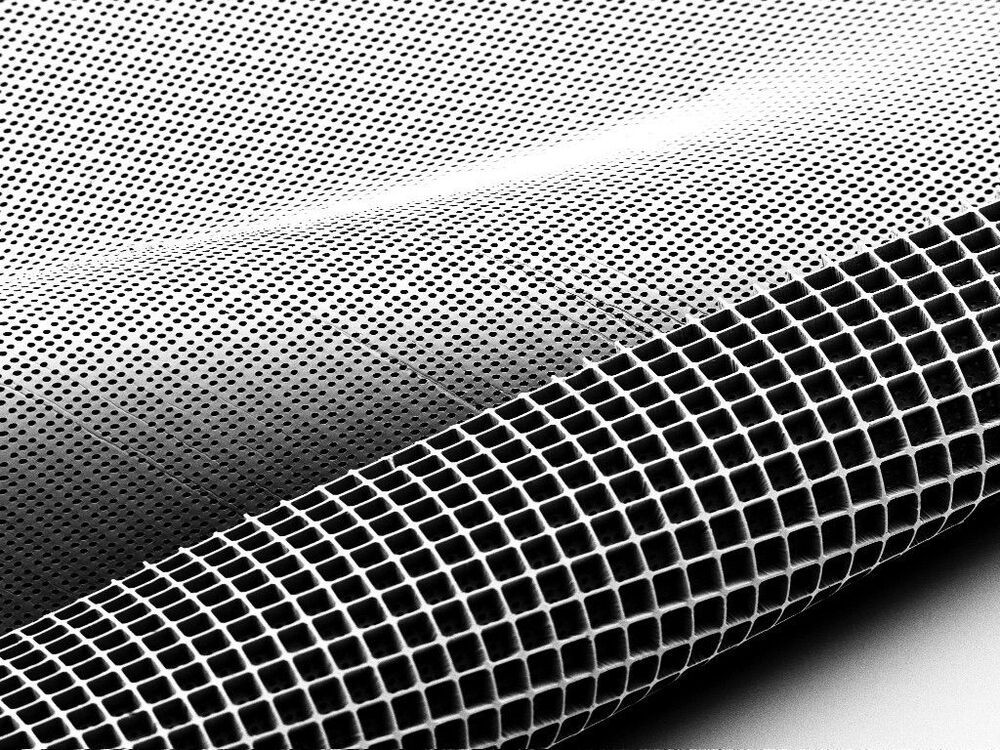

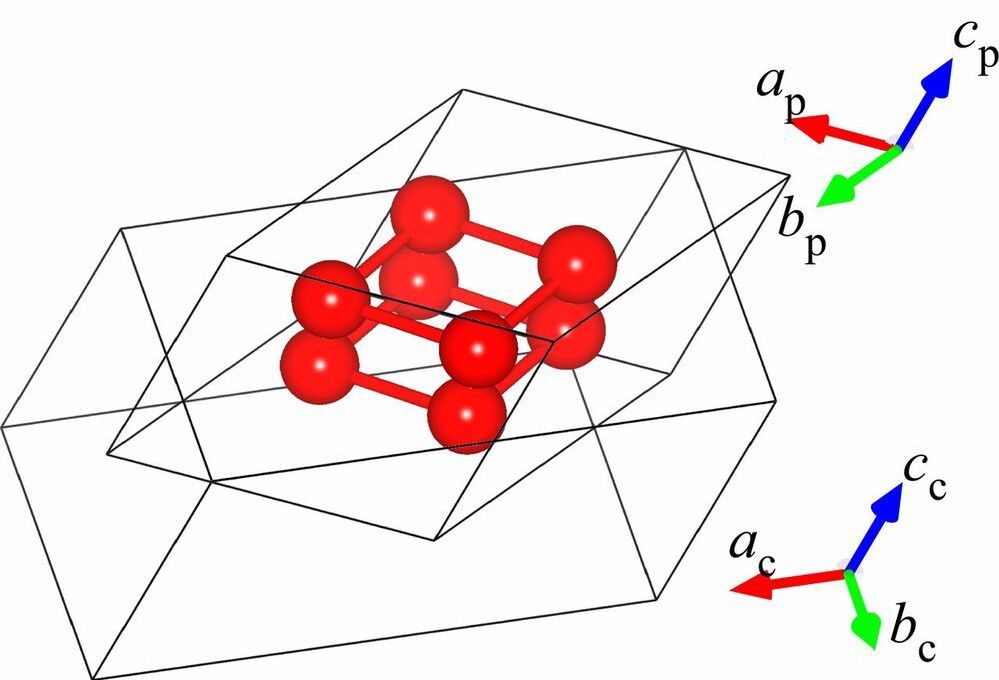

These turbine buckets can be made using laser powder bed fusion, an additive manufacturing technology: Here, the starter material in powder form is built up layer by layer by selective melting with a laser. Following the example of avian bones, intricate lattice structures inside the hollow turbine buckets provide the part with the necessary stability.