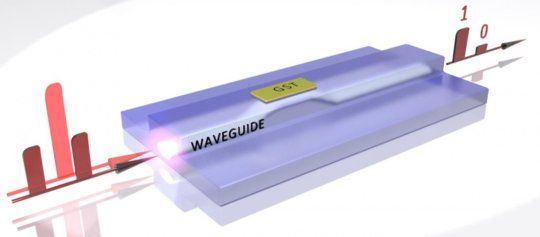

New findings published by quantum scientists in Germany could pave the way towards computer chips that use light instead of electricity to control their internal logic. Where today’s silicon-based electrical computer chips are capable of speeds in the gigahertz range, the German light-based chips would be some 1,000,000 times faster, operating in the petahertz range.

Rather than focusing on an exciting new semiconductor, or some metamaterial that manipulates light in weird and wonderful ways, this research instead revolves around dielectrics. In the field of electronics, materials generally fall into one of three categories: charge carriers (conductors), semiconductors, and dielectrics (insulators). As the name suggests, a semiconductor only conduct electricity some of the time (when it receives a large enough jolt of energy to get its electrons moving). In a dielectric, the electrons are basically immobile, meaning electricity can’t flow across them. Apply too much energy, and you destroy the dielectric. As a general rule, there’s no switching: A dielectric either insulates, or it breaks.

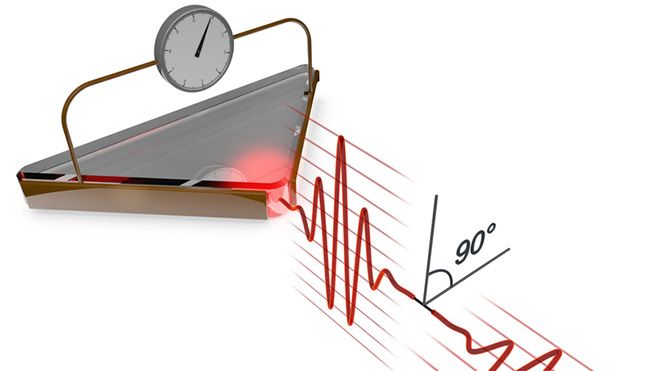

Basically, the Max Planck Institute and Ludwig Maximilian University in Germany have found that dielectrics, using very short bursts of laser light, can be turned into incredibly fast switches. The researchers took a small triangle of silica glass (a strong insulator), and then coated two sides with gold, leaving a small (50nm) gap in between (see below). By shining a femtosecond infrared laser at the gap, the glass started conducting and electricity flowed across the gap. When the laser is turned off, the glass becomes an insulator again.