Can black phosphorous rival #graphene?

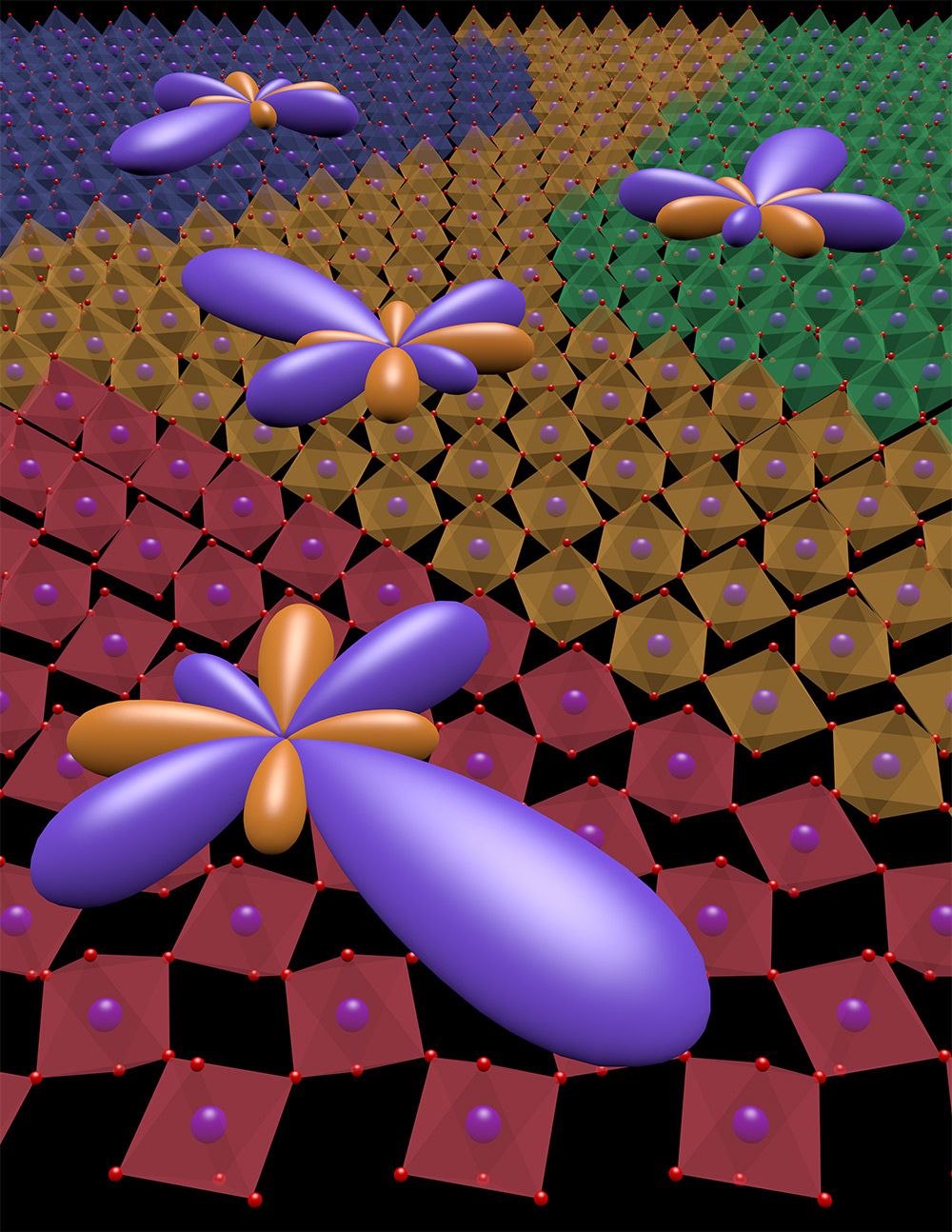

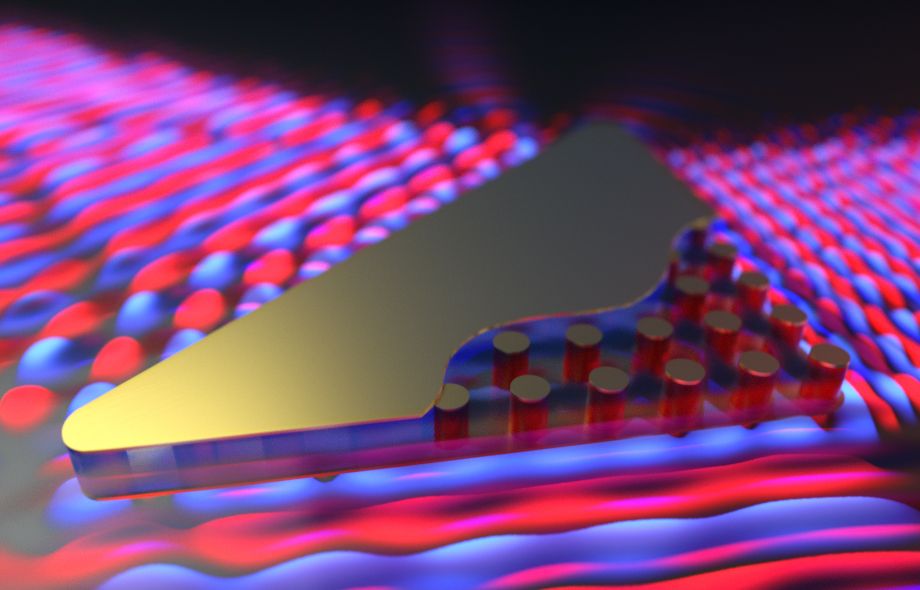

A new experimental revelation about black phosphorus nanoribbons should facilitate the future application of this highly promising material to electronic, optoelectronic and thermoelectric devices. A team of researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has experimentally confirmed strong in-plane anisotropy in thermal conductivity, up to a factor of two, along the zigzag and armchair directions of single-crystal black phosphorous nanoribbons.

“Imagine the lattice of black phosphorous as a two-dimensional network of balls connected with springs, in which the network is softer along one direction of the plane than another,” says Junqiao Wu, a physicist who holds joint appointments with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and the University of California (UC) Berkeley’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering. “Our study shows that in a similar manner heat flow in the black phosphorous nanoribbons can be very different along different directions in the plane. This thermal conductivity anisotropy has been predicted recently for 2D black phosphorous crystals by theorists but never before observed.”

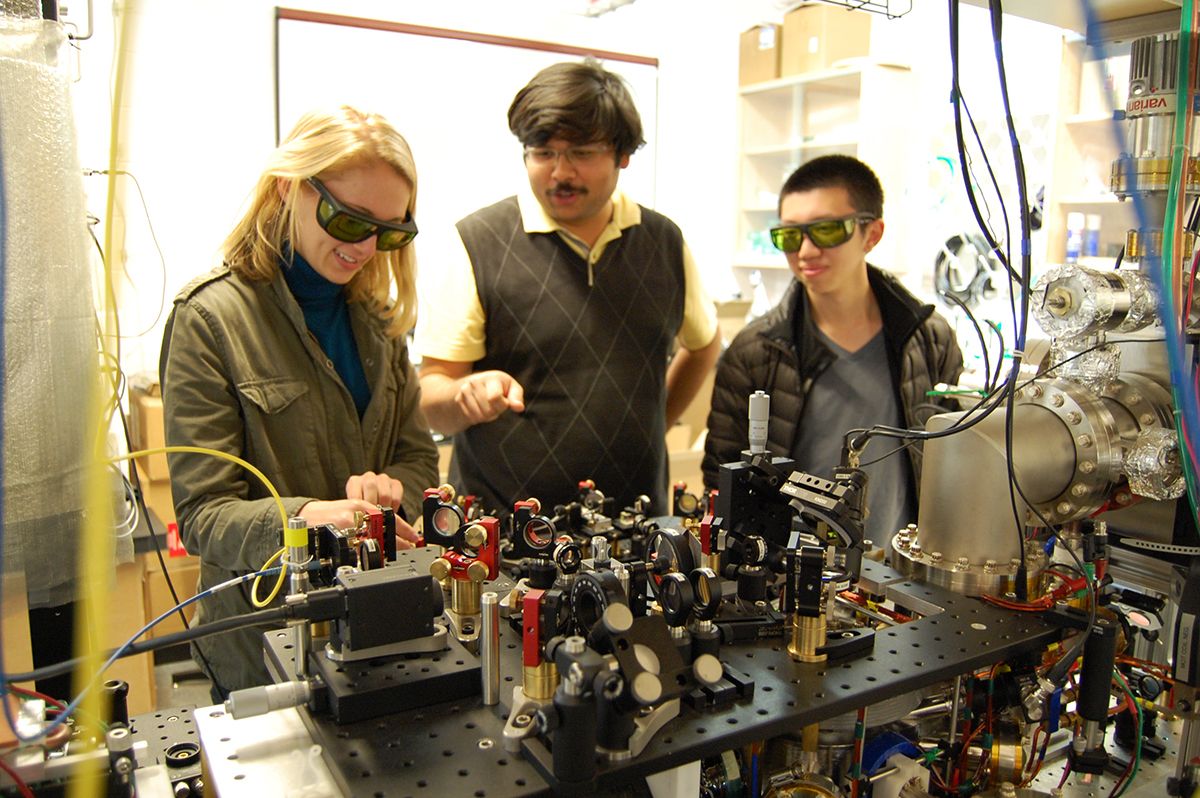

Wu is the corresponding author of a paper describing this research in Nature Communications titled “Anisotropic in-plane thermal conductivity of black phosphorus nanoribbons at temperatures higher than 100K.” The lead authors are Sangwook Lee and Fan Yang. (See below for a complete list of authors)