Circa 2010

In this review, we consider the evidence that a reduction in neurogenesis underlies aging-related cognitive deficits, and impairments in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The molecular and cellular alterations associated with impaired neurogenesis in the aging brain are discussed. Dysfunction of presenilin-1, misprocessing of amyloid precursor protein and toxic effects of hyperphosphorylated tau and β-amyloid likely contribute to impaired neurogenesis in AD. Since factors such as exercise, enrichment and dietary energy restriction enhance neurogenesis, and protect against age-related cognitive decline and AD, knowledge of the underlying neurogenic signaling pathways could lead to novel therapeutic strategies for preserving brain function. In addition, manipulation of endogenous neural stem cells and stem cell transplantation, as stand-alone or adjunct treatments, seem promising.

There is a progressive decline in the regenerative capacity of most organs with increasing age, resulting in functional decline and poor repair from injury and disease. Once thought to exist only in high turnover tissues, such as the intestinal lining or bone marrow, it now appears that most tissues harbor stem cells that contribute to tissue integrity throughout life. In many cases, stem cell numbers decrease with age, suggesting stem cell aging may be of fundamental importance to the biology of aging (for review, see Ref. [1]). Therefore, understanding the regulation of stem cell maintenance and/or activation is of considerable relevance to understanding the age-related decline in maintaining tissue integrity, function, and regenerative response.

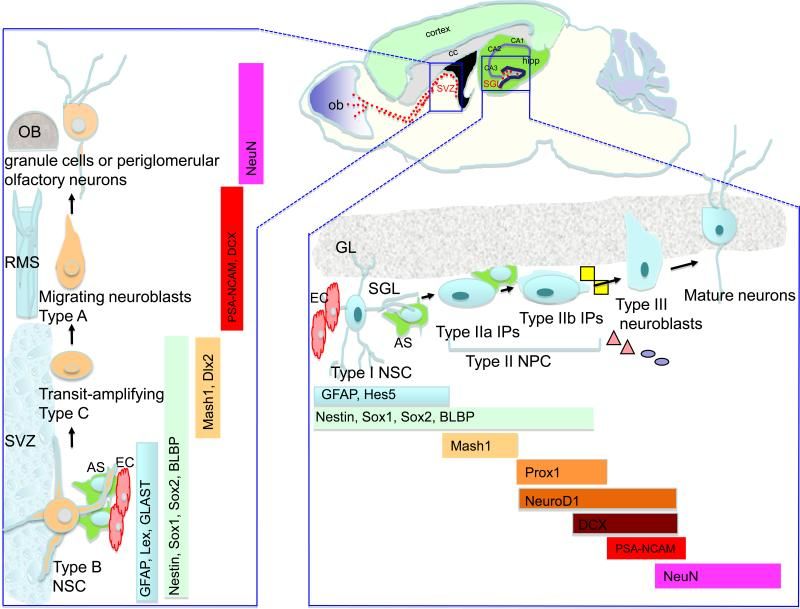

The adult brain contains neural stem cells (NSCs) that self-renew, proliferate and give rise to neural progenitor cells (NPC) that exhibit partial lineage-commitment. Following several cycles of proliferation, NPC differentiate into new neurons and glia. NSCs are increasingly acknowledged to be of functional significance and harbor potential for repair of the diseased or injured brain. The dramatic decline in neurogenesis with age is thought to underlie impairments in learning and memory, at least in part. Aging is also the greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive loss of memory and cognitive decline. Alterations in neurogenesis have been described extensively in animal models of AD, and key proteins involved in AD pathogenesis are shown to regulate neurogenesis.