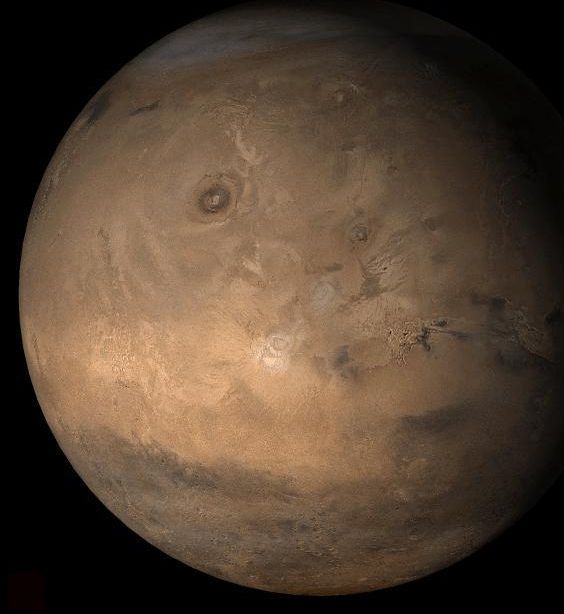

Mars has to have its own internet because no one’s going to wait 20 minutes for a download.

After a string of delays, SpaceX’s Starlink project was finally launched last month. The ambitious aim of the project is to create a “global broadband” system by launching a network of satellites which will eventually be able to give fast internet access from anywhere, even remote locations which currently can’t get broadband internet access.

The project is moving ahead at a considerable pace, with aims to have the first internet access provided by 2021. It may take until November 2027 to get all of the satellites required for the global network launched and into place, but a basic version of the service may be possible with around 1,000 satellites. Within the U.S., some version of the service could be available with just 400 satellites in place.

Naturally, a project of this magnitude requires a huge logistical undertaking and a lot of knowledge from a lot of different sectors. And you can see the takeoff of interest in the Starlink project within SpaceX by analyzing the company’s hiring practices.

Whether you call it Industry 4.0, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), or Smart Manufacturing, the power of technology is being felt throughout the industrial world and fundamentally changing value chains and production methods. Indeed, so great is the change that Capgemini’s Digital Transformation Institute predicts that smart factories could add as much as $1.5 trillion to the overall output of the industrial sector in the next five years. This is because of the turbo-charge effect of smart technology, which is enabling factories to produce more while lowering costs. According to Capgemini, some industries may almost double their operating profit and margin.

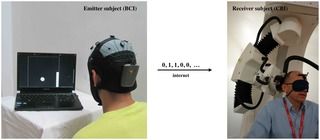

Human sensory and motor systems provide the natural means for the exchange of information between individuals, and, hence, the basis for human civilization. The recent development of brain-computer interfaces (BCI) has provided an important element for the creation of brain-to-brain communication systems, and precise brain stimulation techniques are now available for the realization of non-invasive computer-brain interfaces (CBI). These technologies, BCI and CBI, can be combined to realize the vision of non-invasive, computer-mediated brain-to-brain (B2B) communication between subjects (hyperinteraction). Here we demonstrate the conscious transmission of information between human brains through the intact scalp and without intervention of motor or peripheral sensory systems. Pseudo-random binary streams encoding words were transmitted between the minds of emitter and receiver subjects separated by great distances, representing the realization of the first human brain-to-brain interface. In a series of experiments, we established internet-mediated B2B communication by combining a BCI based on voluntary motor imagery-controlled electroencephalographic (EEG) changes with a CBI inducing the conscious perception of phosphenes (light flashes) through neuronavigated, robotized transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), with special care taken to block sensory (tactile, visual or auditory) cues. Our results provide a critical proof-of-principle demonstration for the development of conscious B2B communication technologies. More fully developed, related implementations will open new research venues in cognitive, social and clinical neuroscience and the scientific study of consciousness. We envision that hyperinteraction technologies will eventually have a profound impact on the social structure of our civilization and raise important ethical issues.

Citation: Grau C, Ginhoux R, Riera A, Nguyen TL, Chauvat H, Berg M, et al. (2014) Conscious Brain-to-Brain Communication in Humans Using Non-Invasive Technologies. PLoS ONE 9: e105225. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.

Editor: Mikhail A. Lebedev, Duke University, United States of America.

Spotlight: FBI Pushes Forward with Massive Biometric Database Despite Privacy Risks.

The Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) focuses public attention on emerging civil liberties, privacy, First Amendment issues and works to promote the Public Voice in decisions concerning the future of the Internet.

My own 2013 book Catalyst: A Techno-Liberation Thesis offered a prediction of the political future, viewing the near-term future as a time of crisis shaped by the nature of technology and the slowness of states to adjust to it. As this struggle becomes more acute, guarded new technologies will also get stolen and overflow across borders, going global and penetrating every country before they were intended to. States and large companies will react with bans and lies as they try to save their monopolies. Ultimately, over a longer time-frame, the nation-state system will collapse because of this pressure and an uncertain successor system of governance will emerge. It will look like “hell on earth” for a time, but it will stabilize in the end. We will become new political animals with new allegiances, shaped by the crisis, much as the Thirty Years’ War brought about our Westphalian nation-state model. Six years on from my book, are we any closer to what I predicted?

Catalyst is read in less than a day, and can be found on Kindle as well as in print. It was written to bring together a number of ideas and predictions I presented in articles at the IEET website, h+ Magazine, and other websites and includes full lists of sources. If you prefer to see more first, follow @CatalystThesis on Twitter or sign up to the email newsletter.

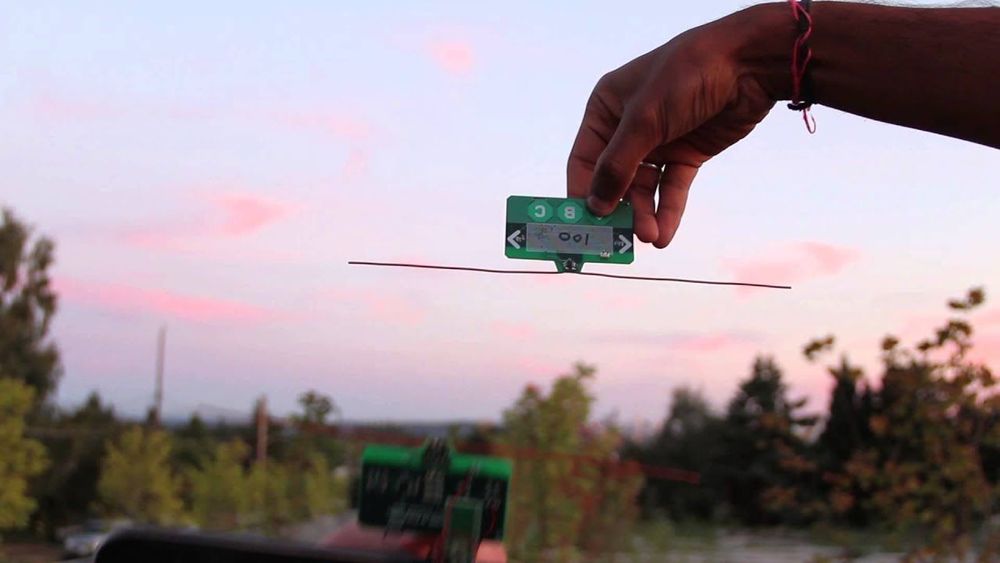

Nowhere is that clearer than in Africa, which has the world’s lowest share of people using the internet, under 25%. The cohort of 800 million offline people spread across the continent’s 54 countries is younger and growing faster than most, but incomes are lower and a larger share of residents live in rural areas that are tough to wire for internet access—or, for that matter, electricity. Now, however, a handful of phone purveyors are trying in greater earnest to nudge internet-ready upgrades into African markets, with models designed with an eye toward rural priorities (first those of rural India, where they’re already hits), rather than battered thirdhand flip phones from the heyday of the Spice Girls.

About half of humanity don’t have internet access, and a lot of those people are in Africa. Enter a $20 device with smartphone brains and a five-day battery.