“Quantum mechanics, a new experiment suggests, requires that multiple adventures occur simultaneously to create a consistent account of history.”

“Quantum mechanics, a new experiment suggests, requires that multiple adventures occur simultaneously to create a consistent account of history.”

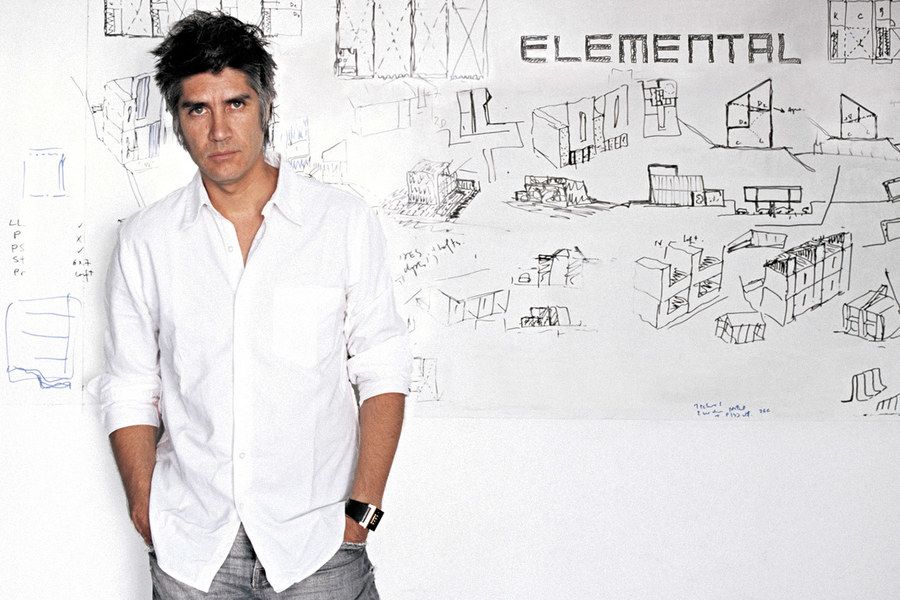

“While Aravena, who is from Chile, is relatively unknown in the United States (although he taught for five years at Harvard and served for a period on the Pritzker jury), for at least the last decade he has been establishing himself on the international architecture scene as a serious and unusual practitioner who straddles, subtly but brilliantly, the worlds of formal high design and social responsibility. He has plenty of credibility as a serious designer—he was recently named curator of the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale—but his own mode of architectural practice is what sets him apart. Aravena runs Elemental, which bills itself as a “do tank”—not a think tank—and which creates “projects of public interest and social impact, including housing, public space, infrastructure and transportation.””

“Alice Paul was the architect of some of the most outstanding political achievements on behalf of women in the 20th century. Born on January 11, 1885 to Quaker parents in Mt. Laurel, New Jersey, Alice Paul dedicated her life to the single cause of securing equal rights for all women.”

“[H]alf the people in the world cram into just 1 percent of the Earth’s surface (in yellow), and the other half sprawl across the remaining 99 percent (in black).”

https://soundcloud.com/kelly-tang-9/sets/nasa-sounds-of-earth

“Programming ‘indestructible’ bacteria to write poetry.”

At one time or another, we’ve all been encouraged to “maximize our potential.” In a recent interview, Academic and Entrepreneur Juan Enriquez said that mankind is making progress toward expanding beyond its potential. And the changes, he believes, could be profound.

To illustrate the process, Enriquez theorized what might happen if we were to bring Charles Darwin back to life and drop him in the middle of Trafalgar Square. As Darwin takes out his notebook and starts observing, Enriquez suggested he would likely see what might appear to be a different species. Since Darwin’s time, humans have grown taller, and with 1.5 billion obese people, larger. Darwin might also notice some other features too that many of us take for granted — there are more senior citizens, more people with all their teeth, a lot fewer wrinkles, and even some 70-year-olds running in marathons.

“There’s a whole series of morphologies that are just different about our bodies, but we don’t notice it. We don’t notice we’ve doubled the lifespan of humans in the last century,” Enriquez said. “We don’t notice how many more informations (sic) come into a brain in a single day versus what used to come in in a lifetime. So, across almost every part of humanity, there have been huge changes.”

Part of the difference that Darwin would see, Enriquez noted, is that natural selection no longer applies as strongly to life and death as it once did. Further, random gene mutations that led to some advantages kept getting passed down to generations and became part of the species. The largest difference, however, is our ongoing move toward intelligent design, he said.

“We’re getting to the stage where we want to tinker with humans. We want to insert this gene so this person doesn’t get a deadly disease. We want to insert this gene so that maybe the person performs better on an 8,000 meter peak climb, or in sports, or in beauty, or in different characteristics,” Enriquez said. “Those are questions we never used to have to face before because there was one way of having sex and now there’s at least 17.”

According to Enriquez, the concept of evolving ourselves is an important one because we are the first and only species on earth that has deliberately taken control over the pattern of evolution of what lives and dies (Science Magazine seems to agree). The technologies we’re developing now towards this goal provide us with an instrument for the a potential longer survival of the species than might otherwise be possible.

Those notions, however, raise a number of moral and ethical questions. “What is humanity…where do we want to take it?” Enriquez poses. While he noted that it’s easy to project that tinkering with humanity will lead to a dystopic future, he remains cautiously optimistic about our potential.

“I think we’ve become a much more domesticated species. We’re far less likely to murder each other than we were 50 years ago, 100 years ago or 200 years ago. We have learned how to live together in absolutely massive cities,” Enriquez said. “I think we have become far more tolerant of other religions (and) other races. There are places where this hasn’t happened but, on the whole, life has gotten a whole lot better in the last two or three hundred years and as you’re looking at that, I think we will have the tolerance for different choices made with these very instruments, and I think that’s a good thing.”

As he looks at the future of evolving humanity, Enriquez sees reasons for a great deal of optimism in the realm of single gene modification, especially in the area of eradicating disease and inherited conditions. The consequences, however, are still an unknown.

“In the UK, there was a question, ‘Do we insert gene code into a fertilized egg to cure a deadly disease?’ That is a real question, because that would keep these babies from dying early from these horrendous diseases,” Enriquez said. “The consequences of that are, for the first time, probably in the next year, you’ll have the first child born to three genetic parents.”

The path toward evolving human intelligence in the near future isn’t as cut and dry, Enriquez said. Once we establish the implications and morality between governments, religious organizations, and the scientific community, there are still plenty of hurdles to clear.

“There have been massive studies in China and we haven’t yet identified genes correlated to intelligence, even though we believe intelligence has significant inherited capacity,” Enriquez said. “I think you have to separate reality from fiction. The ability to insert a gene or two, and really modify the intelligence of human beings, I think, is highly unlikely in the next decade or two decades.”

“Plenty of forward-thinking companies have innovation divisions that try and predict the future, disrupt old models, and develop cutting-edge products. They don’t nest those divisions inside their human resources departments. So why shouldn’t gender diversity efforts be a part of corporate innovation?”

In the various incarnations of Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, a sentient robot named Marvin the Paranoid Android serves on the starship Heart of Gold. Because he is never assigned tasks that challenge his massive intellect, Marvin is horribly depressed, always quite bored, and a burden to the humans and aliens around him. But he does write nice lullabies.

While Marvin is a fictional robot, Scholar and Author David Gunkel predicts that sentient robots will soon be a fact of life and that mankind needs to start thinking about how we’ll treat such machines, at present and in the future.

For Gunkel, the question is about moral standing and how we decide if something does or does not have moral standing. As an example, Gunkel notes our children have moral standing, while a rock or our smartphone may not have moral consideration. From there, he said, the question becomes, where and how do we draw the line to decide who is inside and who is outside the moral community?

“Traditionally, the qualities for moral standing are things like rationality, sentience (and) the ability to use languages. Every entity that has these properties generally falls into the community of moral subjects,” Gunkel said. “The problem, over time, is that these properties have changed. They have not been consistent.”

To illustrate, Gunkel cited Greco-Roman times, when land-owning males were allowed to exclude their wives and children from moral consideration and basically treat them as property. As we’ve grown more enlightened in recent times, Gunkel points to the animal rights movement which, he said, has lowered the bar for inclusion in moral standing, based on the questions of “Do they suffer?” and “Can they feel?” The properties that are qualifying properties are no longer as high in the hierarchy as they once were, he said.

While the properties approach has worked well for about 2,000 years, Gunkel noted that it has generated more questions that need to be answered. On the ontological level, those questions include, “How do we know which properties qualify and when do we know when we’ve lowered the bar too low or raised it too high? Which properties count the most?”, and, more importantly, “Who gets to decide?”

“Moral philosophy has been a struggle over (these) questions for 2,000 years and, up to this point, we don’t seem to have gotten it right,” Gunkel said. “We seem to have gotten it wrong more often than we have gotten it right… making exclusions that, later on, are seen as being somehow problematic and dangerous.”

Beyond the ontological issues, Gunkel also notes there are epistemological questions to be addressed as well. If we were to decide on a set of properties and be satisfied with those properties, because those properties generally are internal states, such as consciousness or sentience, they’re not something we can observe directly because they happen inside the cranium or inside the entity, he said. What we have to do is look at external evidence and ask, “How do I know that another entity is a thinking, feeling thing like I assume myself to be?”

To answer that question, Gunkel noted the best we can do is assume or base our judgments on behavior. The question then becomes, if you create a machine that is able to simulate pain, as we’ve been able to do, do you assume the robots can read pain? Citing Daniel Dennett’s essay Why You Can’t Make a Computer That Feels Pain, Gunkel said the reason we can’t build a computer that feels pain isn’t because we can’t engineer a mechanism, it’s because we don’t know what pain is.

“We don’t know how to make pain computable. It’s not because we can’t do it computationally, but because we don’t even know what we’re trying to compute,” he said. “We have assumptions and think we know what it is and experience it, but the actual thing we call ‘pain’ is a conjecture. It’s always a projection we make based on external behaviors. How do we get legitimate understanding of what pain is? We’re still reading signs.”

According to Gunkel, the approaching challenge in our everyday lives is, “How do we decide if they’re worthy of moral consideration?” The answer is crucial, because as we engineer and build these devices, we must still decide what we do with “it” as an entity. This concept was captured in a PBS Idea Channel video, an episode based on this idea and on Gunkel’s book, The Machine Question.

To address that issue, Gunkel said society should consider the ethical outcomes of the artificial intelligence we create at the design stage. Citing the potential of autonomous weapons, the question is not whether or not we should use the weapon, but whether we should even design these things at all.

“After these things are created, what do we do with them, how do we situate them in our world? How do we relate to them once they are in our homes and in our workplace? When the machine is there in your sphere of existence, what do we do in response to it?” Gunkel said. “We don’t have answers to that yet, but I think we need to start asking those questions in an effort to begin thinking about what is the social status and standing of these non-human entities that will be part of our world living with us in various ways.”

As he looks to the future, Gunkel predicts law and policy will have a major effect on how artificial intelligence is regarded in society. Citing decisions stating that corporations are “people,” he noted that the same types of precedents could carry over to designed systems that are autonomous.

“I think the legal aspect of this is really important, because I think we’re making decisions now, well in advance of these kind of machines being in our world, setting a precedent for the receptivity to the legal and moral standing of these other kind of entities,” Gunkel said.

“I don’t think this will just be the purview of a few philosophers who study robotics. Engineers are going to be talking about it. AI scientists have got to be talking about it. Computer scientists have got to be talking about it. It’s got to be a fully interdisciplinary conversation and it’s got to roll out on that kind of scale.”

It seems like every day we’re warned about a new, AI-related threat that could ultimately bring about the end of humanity. According to Author and Oxford Professor Nick Bostrom, those existential risks aren’t so black and white, and an individual’s ability to influence those risks might surprise you.

Image Credit: TEDBostrom defines an existential risk as one distinction of earth originating life or the permanent and drastic destruction of our future development, but he also notes that there is no single methodology that is applicable to all the different existential risks (as more technically elaborated upon in this Future of Humanity Institute study). Rather, he considers it an interdisciplinary endeavor.

“If you’re wondering about asteroids, we have telescopes, we can study them with, we can look at past crater impacts and derive hard statistical data on that,” he said. “We find that the risk of asteroids is extremely small and likewise for a few of the other risks that arrive from nature. But other really big existential risks are not in any direct way susceptible to this kind of rigorous quantification.”

In Bostrom’s eyes, the most significant risks we face arise from human activity and particularly the potential dangerous technological discoveries that await us in the future. Though he believes there’s no way to quantify the possibility of humanity being destroyed by a super-intelligent machine, a more important variable is human judgment. To improve assessment of existential risk, Bostrom said we should think carefully about how these judgments are produced and whether the biases that affect those judgments can be avoided.

“If your task is to hammer a nail into a board, reality will tell you if you’re doing it right or not. It doesn’t really matter if you’re a Communist or a Nazi or whatever crazy ideologies you have, you’ll learn quite quickly if you’re hammering the nail in wrong,” Bostrom said. “If you’re wrong about what the major threats are to humanity over the next century, there is not a reality click to tell you if you’re right or wrong. Any weak bias you might have might distort your belief.”

Noting that humanity doesn’t really have any policy designed to steer a particular course into the future, Bostrom said many existential risks arise from global coordination failures. While he believes society might one day evolve into a unified global government, the question of when this uniting occurs will hinge on individual contributions.

“Working toward global peace is the best project, just because it’s very difficult to make a big difference there if you’re a single individual or a small organization. Perhaps your resources would be better put to use if they were focused on some problem that is much more neglected, such as the control problem for artificial intelligence,” Bostrom said. “(For example) do the technical research to figure that, if we got the ability to create super intelligence, the outcome would be safe and beneficial. That’s where an extra million dollars in funding or one extra very talented person could make a noticeable difference… far more than doing general research on existential risks.”

Looking to the future, Bostrom feels there is an opportunity to show that we can do serious research to change global awareness of existential risks and bring them into a wider conversation. While that research doesn’t assume the human condition is fixed, there is a growing ecosystem of people who are genuinely trying to figure out how to save the future, he said. As an example of how much influence one can have in reducing existential risk, Bostrom noted that a lot more people in history have believed they were Napoleon, yet there was actually only one Napoleon.

“You don’t have to try to do it yourself… it’s usually more efficient to each do whatever we specialize in. For most people, the most efficient way to contribute to eliminating existential risk would be to identify the most efficient organizations working on this and then support those,” Bostrom said. “The values on the line in terms of how many happy lives could exist in humanity’s future, even a very small probability of impact in that, would probably be worthwhile in pursuing”.

This piece is dedicated to Stefan Stern, who picked up on – and ran with – a remark I made at this year’s Brain Bar Budapest, concerning the need for a ‘value-added’ account of being ‘human’ in a world in which there are many drivers towards replacing human labour with ever smarter technologies.

In what follows, I assume that ‘human’ can no longer be taken for granted as something that adds value to being-in-the-world. The value needs to be earned, it can’t be just inherited. For example, according to animal rights activists, ‘value-added’ claims to brand ‘humanity’ amount to an unjustified privileging of the human life-form, whereas artificial intelligence enthusiasts argue that computers will soon exceed humans at the (‘rational’) tasks that we have historically invoked to create distance from animals. I shall be more concerned with the latter threat, as it comes from a more recognizable form of ‘economistic’ logic.

Economics makes an interesting but subtle distinction between ‘price’ and ‘cost’. Price is what you pay upfront through mutual agreement to the person selling you something. In contrast, cost consists in the resources that you forfeit by virtue of possessing the thing. Of course, the cost of something includes its price, but typically much more – and much of it experienced only once you’ve come into possession. Thus, we say ‘hidden cost’ but not ‘hidden price’. The difference between price and cost is perhaps most vivid when considering large life-defining purchases, such as a house or a car. In these cases, any hidden costs are presumably offset by ‘benefits’, the things that you originally wanted — or at least approve after the fact — that follow from possession.

Now, think about the difference between saying, ‘Humanity comes at a price’ and ‘Humanity comes at a cost’. The first phrase suggests what you need to pay your master to acquire freedom, while the second suggests what you need to suffer as you exercise your freedom. The first position has you standing outside the category of ‘human’ but wishing to get in – say, as a prospective resident of a gated community. The second position already identifies you as ‘human’ but perhaps without having fully realized what you had bargained for. The philosophical movement of Existentialism was launched in the mid-20th century by playing with the irony implied in the idea of ‘human emancipation’ – the ease with which the Hell we wish to leave (and hence pay the price) morphs into the Hell we agree to enter (and hence suffer the cost). Thus, our humanity reduces to the leap out of the frying pan of slavery and into the fire of freedom.

In the 21st century, the difference between the price and cost of humanity is being reinvented in a new key, mainly in response to developments – real and anticipated – in artificial intelligence. Today ‘humanity’ is increasingly a boutique item, a ‘value-added’ to products and services which would be otherwise rendered, if not by actual machines then by humans trying to match machine-based performance standards. Here optimists see ‘efficiency gains’ and pessimists ‘alienated labour’. In either case, ‘humanity comes at a price’ refers to the relative scarcity of what in the past would have been called ‘craftsmanship’. As for ‘humanity comes at a cost’, this alludes to the difficulty of continuing to maintain the relevant markers of the ‘human’, given both changes to humans themselves and improvements in the mechanical reproduction of those changes.

Two prospects are in the offing for the value-added of being human: either (1) to be human is to be the original with which no copy can ever be confused, or (2) to be human is to be the fugitive who is always already planning its escape as other beings catch up. In a religious vein, we might speak of these two prospects as constituting an ‘apophatic anthropology’, that is, a sense of the ‘human’ the biggest threat to which is that it might be nailed down. This image was originally invoked in medieval Abrahamic theology to characterize the unbounded nature of divine being: God as the namer who cannot be named.

But in a more secular vein, we can envisage on the horizon two legal regimes, which would allow for the routine demonstration of the ‘value added’ of being human. In the case of (1), the definition of ‘human’ might come to be reduced to intellectual property-style priority disputes, whereby value accrues simply by virtue of showing that one is the originator of something of already proven value. In the case of (2), the ‘human’ might come to define a competitive field in which people routinely try to do something that exceeds the performance standards of non-human entities – and added value attaches to that achievement.

Either – or some combination – of these legal regimes might work to the satisfaction of those fated to live under them. However, what is long gone is any idea that there is an intrinsic ‘value-added’ to being human. Whatever added value there is, it will need to be fought for tooth and nail.