A new, rare genetic form of dementia has been discovered by a team of Penn Medicine researchers. This discovery also sheds light on a new pathway that leads to protein build up in the brain—which causes this newly discovered disease, as well as related neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s Disease—that could be targeted for new therapies. The study was published today in Science.

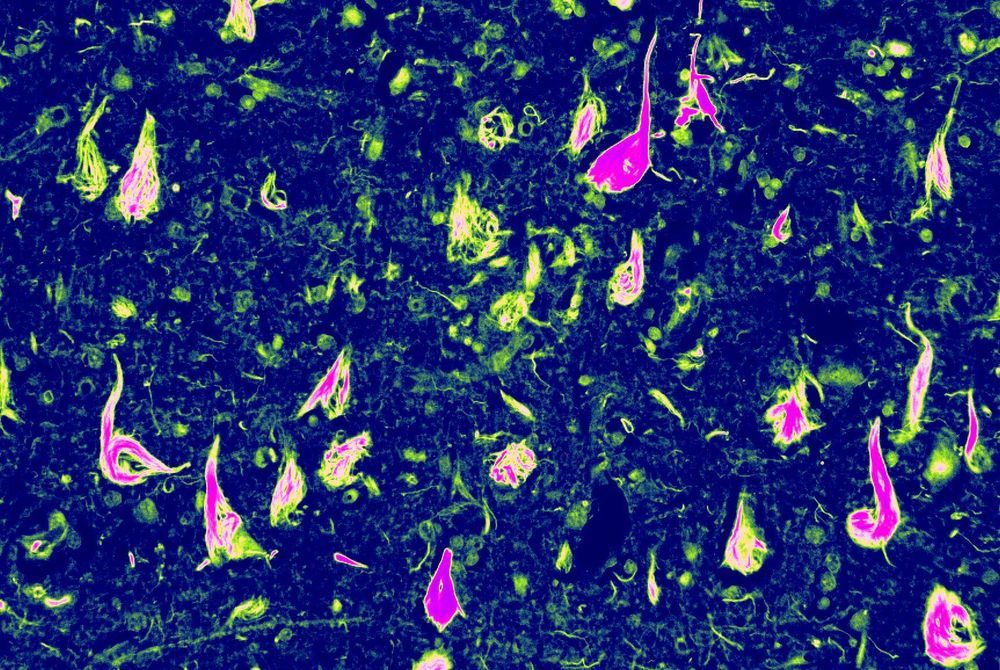

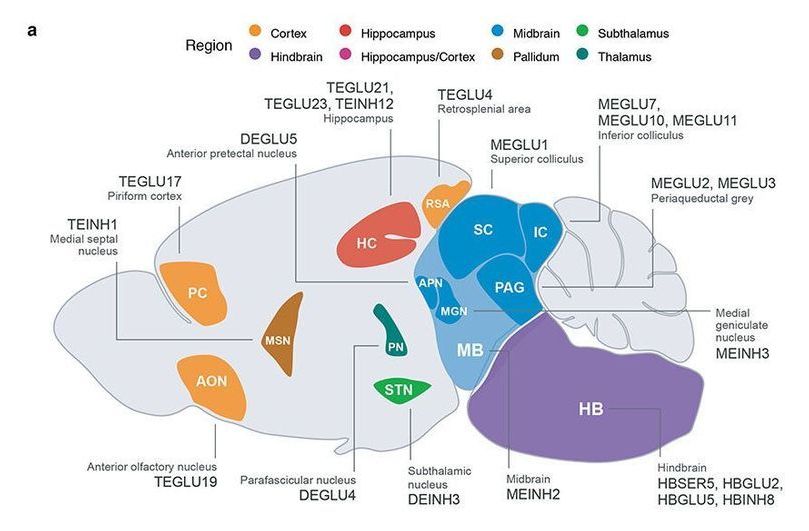

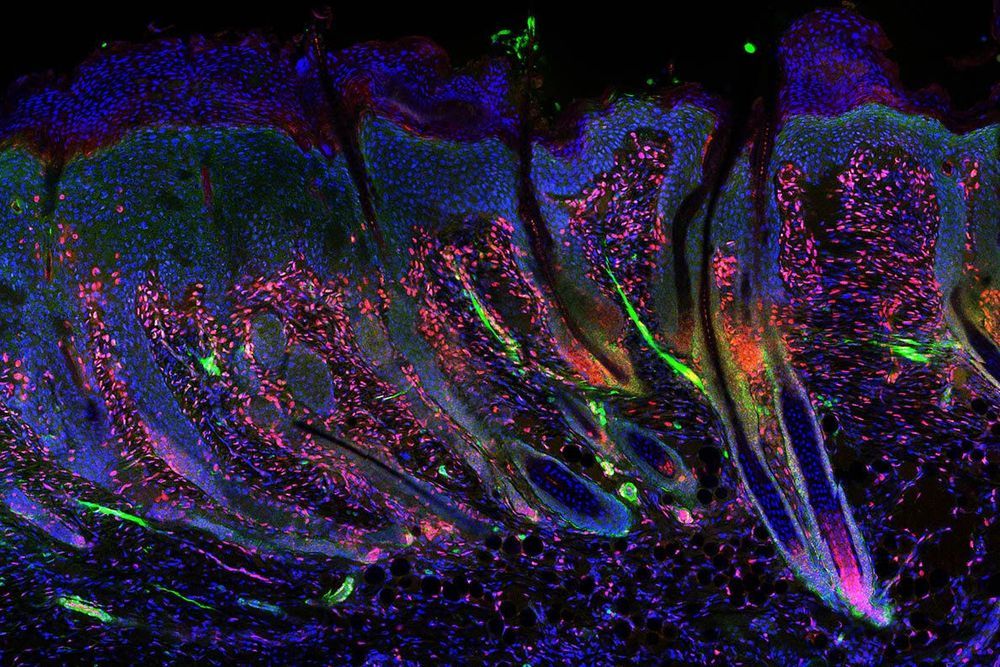

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by a buildup of proteins, called tau proteins, in certain parts of the brain. Following an examination of human brain tissue samples from a deceased donor with an unknown neurodegenerative disease, researchers discovered a novel mutation in the Valosin-containing protein (VCP) gene in the brain, a buildup of tau proteins in areas that were degenerating, and neurons with empty holes in them, called vacuoles. The team named the newly discovered disease Vacuolar Tauopathy (VT)—a neurodegenerative disease now characterized by the accumulation of neuronal vacuoles and tau protein aggregates.

“Within a cell, you have proteins coming together, and you need a process to also be able to pull them apart, because otherwise everything kind of gets gummed up and doesn’t work. VCP is often involved in those cases where it finds proteins in an aggregate and pulls them apart,” Edward Lee, MD, Ph.D., an assistant professor of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “We think that the mutation impairs the proteins’ normal ability to break aggregates apart.”