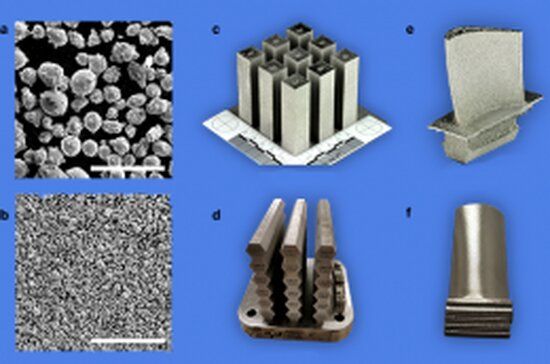

In recent years, it has become possible to use laser beams and electron beams to “print” engineering objects with complex shapes that could not be achieved by conventional manufacturing. The additive manufacturing (AM) process, or 3D printing, for metallic materials involves melting and fusing fine-scale powder particles—each about 10 times finer than a grain of beach sand—in sub-millimeter-scale “pools” created by focusing a laser or electron beam on the material.

“The highly focused beams provide exquisite control, enabling ‘tuning’ of properties in critical locations of the printed object,” said Tresa Pollock, a professor of materials and associate dean of the College of Engineering at UC Santa Barbara. “Unfortunately, many advanced metallic alloys used in extreme heat-intensive and chemically corrosive environments encountered in energy, space and nuclear applications are not compatible with the AM process.”

The challenge of discovering new AM-compatible materials was irresistible for Pollock, a world-renowned scientist who conducts research on advanced metallic materials and coatings. “This was interesting,” she said, “because a suite of highly compatible alloys could transform the production of metallic materials having high economic value—i.e. materials that are expensive because their constituents are relatively rare within the earth’s crust—by enabling the manufacture of geometrically complex designs with minimal material waste.