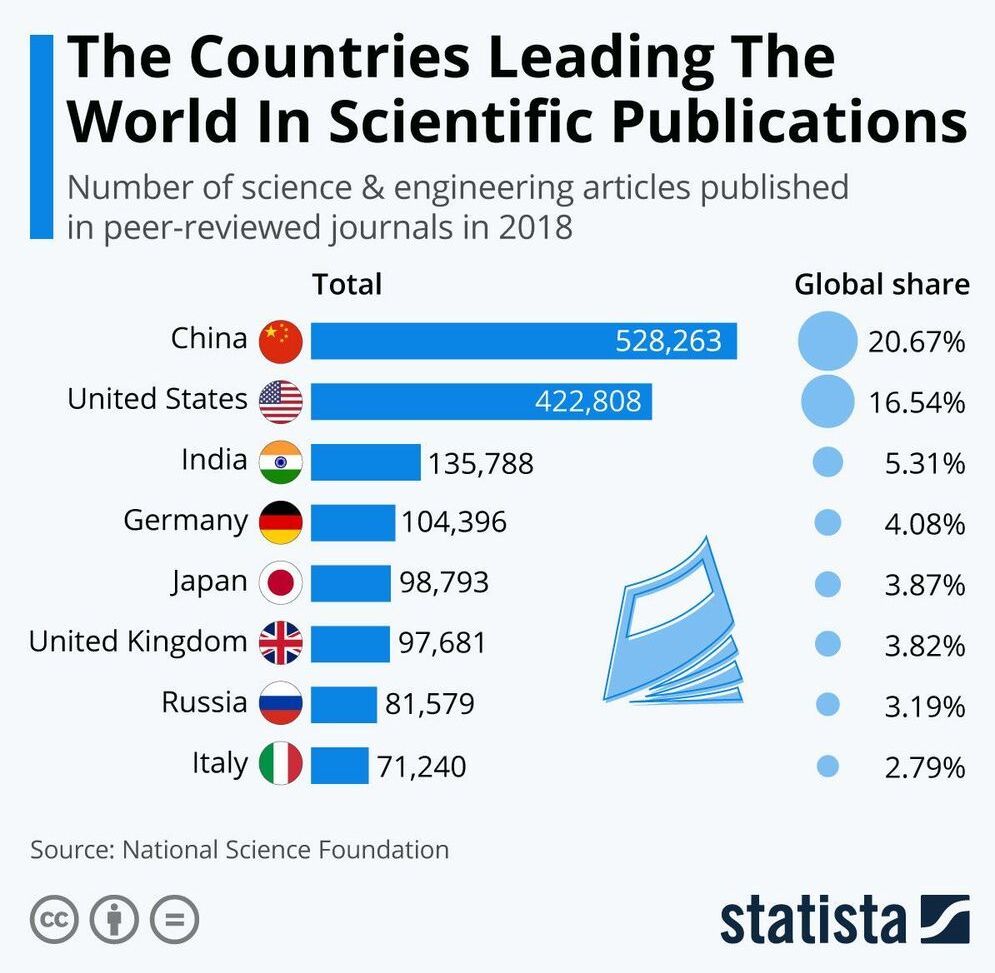

China keeps leading the US on investments in tech.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) has released data showing that 2555, 959 science and engineering (S&E) articles were published around the world in 2018, a considerable increase on the 1755, 850 recorded a decade ago. Global research output in that sector has grown around 4 percent annually over the past ten years and China’s growth rate is notable as being twice the world average. While the U.S. led the way in 2008, it has now been displaced as the world’s top S&E research publisher by China.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.