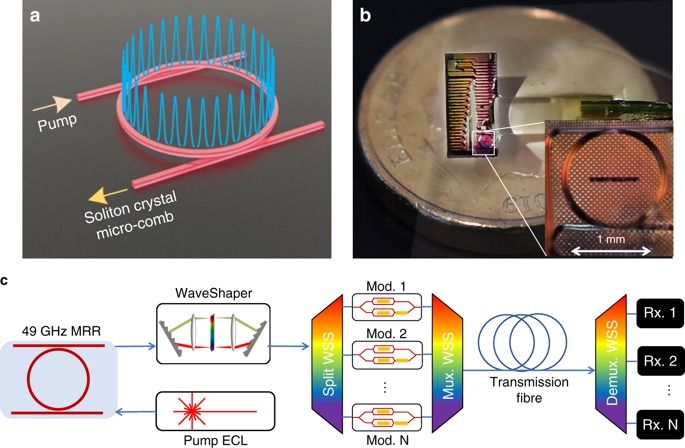

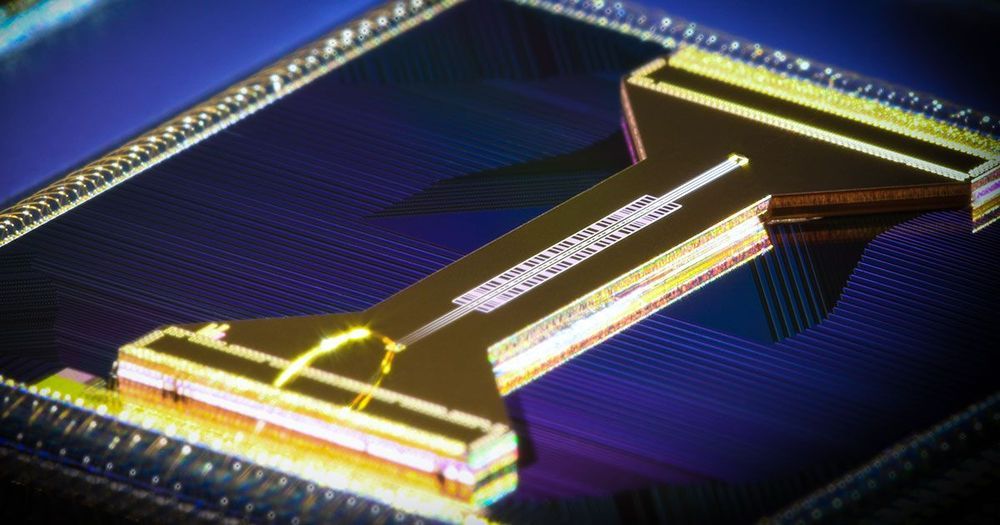

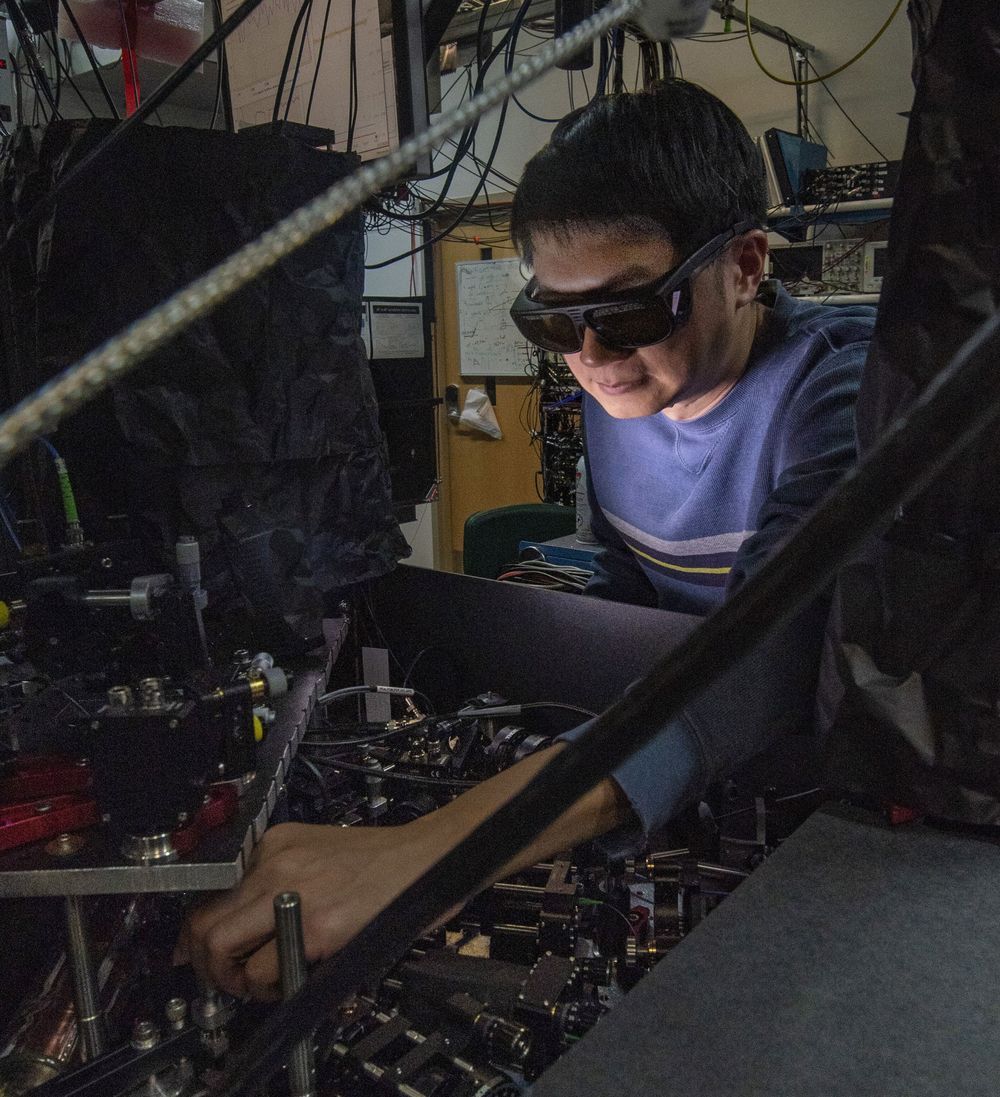

Micro-combs — optical frequency combs generated by integrated micro-cavity resonators – offer the full potential of their bulk counterparts, but in an integrated footprint. They have enabled breakthroughs in many fields including spectroscopy, microwave photonics, frequency synthesis, optical ranging, quantum sources, metrology and ultrahigh capacity data transmission. Here, by using a powerful class of micro-comb called soliton crystals, we achieve ultra-high data transmission over 75 km of standard optical fibre using a single integrated chip source. We demonstrate a line rate of 44.2 Terabits s−1 using the telecommunications C-band at 1550 nm with a spectral efficiency of 10.4 bits s−1 Hz−1. Soliton crystals exhibit robust and stable generation and operation as well as a high intrinsic efficiency that, together with an extremely low soliton micro-comb spacing of 48.9 GHz enable the use of a very high coherent data modulation format (64 QAM — quadrature amplitude modulated). This work demonstrates the capability of optical micro-combs to perform in demanding and practical optical communications networks.