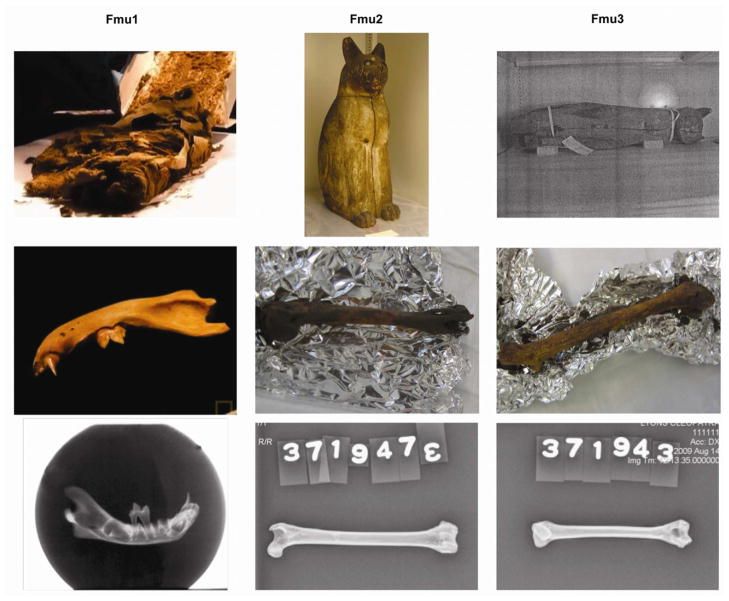

The ancient Egyptians mummified an abundance of cats during the Late Period (664 — 332 BC). The overlapping morphology and sizes of developing wildcats and domestic cats confounds the identity of mummified cat species. Genetic analyses should support mummy identification and was conducted on two long bones and a mandible of three cats that were mummified by the ancient Egyptians. The mummy DNA was extracted in a dedicated ancient DNA laboratory at the University of California – Davis, then directly sequencing between 246 and 402 bp of the mtDNA control region from each bone. When compared to a dataset of wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris, F. s. tristrami, and F. chaus) as well as a previously published worldwide dataset of modern domestic cat samples, including Egypt, the DNA evidence suggests the three mummies represent common contemporary domestic cat mitotypes prevalent in modern Egypt and the Middle East. Divergence estimates date the origin of the mummies’ mitotypes to between two and 7.5 thousand years prior to their mummification, likely prior to or during Egyptian Predyanstic and Early Dynastic Periods. These data are the first genetic evidence supporting that the ancient Egyptians used domesticated cats, F. s. catus, for votive mummies, and likely implies cats were domesticated prior to extensive mummification of cats.

Keywords: ancient DNA, Felis silvestris catus, mitochondrial, control region, domestication.

Ancient Egyptian culture is well known for its reverence and mummification of cats (Ginsburg, et al., 1991). Cats featured in early Egyptian art and skeletal remains from c. 4000 BC, has led scholars to conclude that our current feline companions might have been domesticated in Egypt (Baldwin, 1975, Ginsburg, et al., 1991, Linseele, et al., 2007). However, the first documentation of wildcat taming, the precursor to domestication, is an archeological finding in Cyprus of a potential wildcat buried with a human, dating to approximately 9500 years ago (Vigne, et al., 2004), implying prior to the Predynastic Period in Egypt. Recent genetic studies have suggested that the origins of cat domestication occurred in the adjacent Near Eastern sites (Driscoll, et al., 2007, Lipinski, et al., 2008) as domestic cats have derived mitotypes from regional wildcats and the genetic diversity of modern domestic cats is highest within these regions.

Learn more about how we can tackle PPE pollution:

Learn more about how we can tackle PPE pollution: