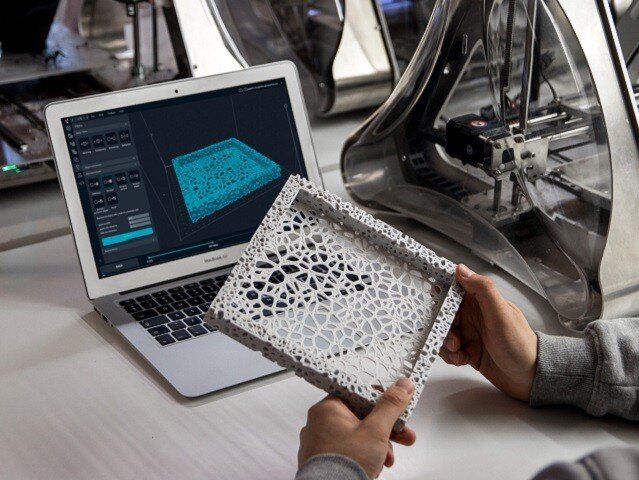

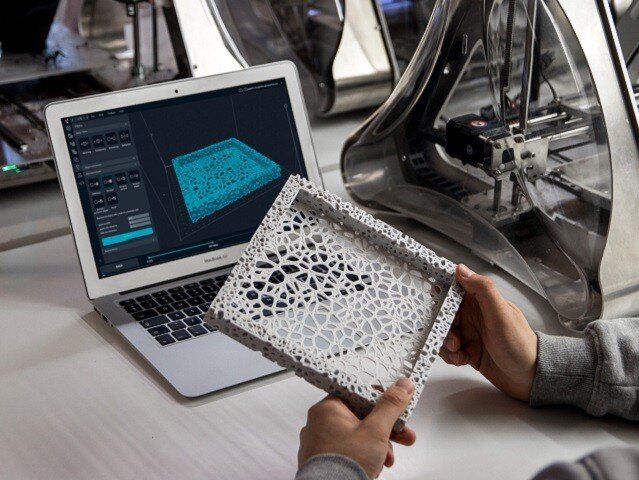

3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, has become widespread in recent years. By building successive layers of raw material such as metals, plastics, and ceramics, it has the key advantage of being able to produce very complex shapes or geometries that would be nearly impossible to construct through more traditional methods such as carving, grinding, or molding.

The technology offers huge potential in the health care sector. For example, doctors can use it to make products to match a patient’s anatomy: a radiologist could create an exact replica of a patient’s spine to help plan surgery; a dentist could scan a patient’s broken tooth to make a perfectly fitting crown reproduction. But what if we took a step further and apply 3D printing techniques to neuroscience?

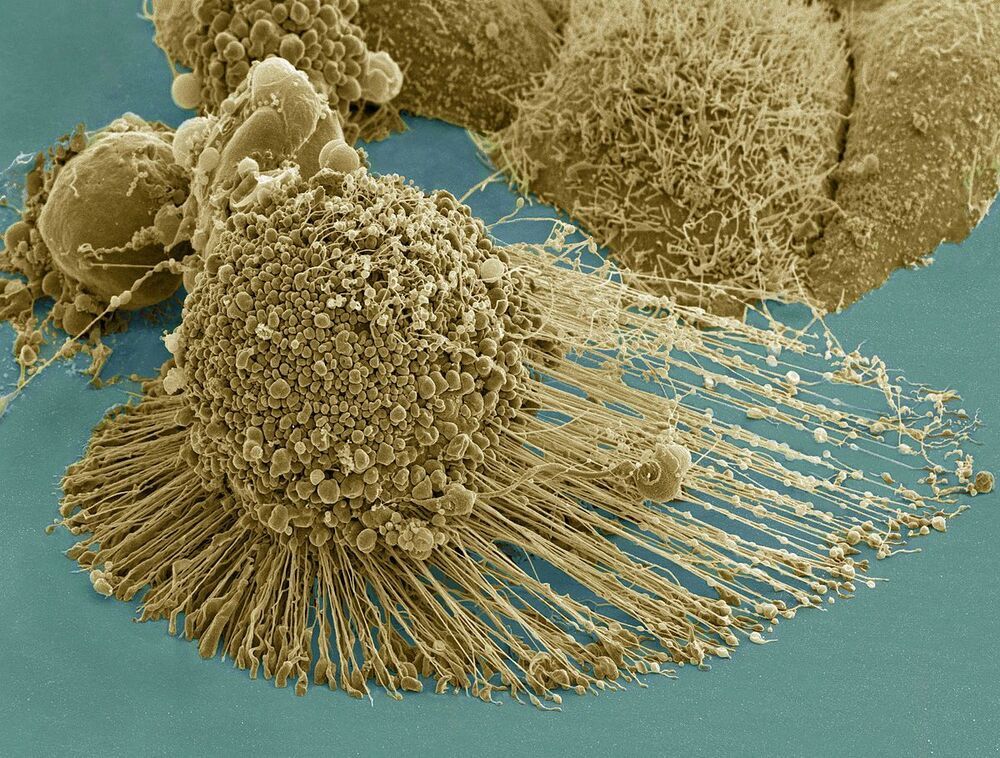

Stems cells are essentially the body’s raw materials; they are pluripotent elements from which all other cells with specialized functions are generated. The development of methods to isolate and generate human stem cells, has excited many with the promise of improved human cell function understanding, ultimately utilizing them for regeneration in disease and trauma. However, the traditional two-dimensional growth of derived neurones–using flat petri dishes–presents itself as a major confounding factor as it does not adequately mimic in vivo three-dimensional interactions, nor the myriad developmental cues present in real living organisms.

To address this limitation in current neuronal culturing approaches, the FET funded MESO-BRAIN project, led by Aston University, proposed a highly ambitious interdisciplinary enterprise to construct truly 3D networks that not only displayed in vivo activity patterns of neural cultures but also allowed for precise interaction with these cultures. This allows the activity of individual elements to be readily monitored and controlled through electrical stimulation.

The ability to develop human-induced pluripotent stem cell derived neural networks upon a defined and reproducible 3D scaffold that can emulate brain activity, allows for a comprehensive and detailed investigation of neural network development.

The MESO-BRAIN project facilitates a better understanding of human disease progression, neuronal growth and enables the development of large-scale human cell-based assays to test the modulatory effects of pharmacological and toxicological compounds on neural network activity. This can ultimately help to better understand and treat neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, dementia, and trauma. In addition, the use of more physiologically relevant human models will increase drug screening efficiency and reduce the need for animal testing.