Game-changing technologies can be a waste of money or a competitive advantage. It depends on the technology and the organization.

It seems like the term “game-changing” gets tossed around a lot lately. This is particularly true with respect to new technologies. But what does the term mean, what are the implications, and how can you measure it?

With regarding to what it means, I like the MacMillan dictionary definition for game-changing. It is defined as “Completely changing the way that something is done, thought about, or made.” The reason I like this definition is it captures the transformational nature of what springs to mind when I hear the term game-changing. This should be just what it says. Not just a whole new ball game, but a whole new type of game entirely.

Every industry is unique. What is a game-changer for one, might only be a minor disruption or improvement for another. For example, the internal combustion engine was a game-changer for the transportation industry. It was important, though less of a game-changer for the asphalt industry due to secondary effect of increased demand for paved roads.

Just as every industry is unique, so is every organization. In order to prosper in a dynamic environment, an organization must be able to evaluate how a particular technology will affect its strategic goals, as well as its current operations. For this to happen, an organization’s leadership must have a clear understanding of itself and the environment in which it is operating. While this seems obvious, for large complex organizations, it may not be as easy as it sounds.

In addition to organizational awareness, leadership must have the inclination and ability to run scenarios of how it the organization be affected by the candidate game-changer. These scenarios provides the ability to peek a little into the future, and enables leadership to examine different aspects of the potential game-changer’s immediate and secondary impacts.

Now there are a lot of potential game-changers out there, and it is probably not possible to run a full evaluation on all of them. Here is where an initial screening comes in useful. An initial screen might ask is it realistic, actionable, and scalable? Realistic means does it appear to be feasible from a technical and financial standpoint? Actionable means does this seem like something that can actually be produced? Scalable means will the infrastructure support rapid adoption? If a potentially transformational technology passes this initial screening, then its impact on the organization should be thoroughly evaluated.

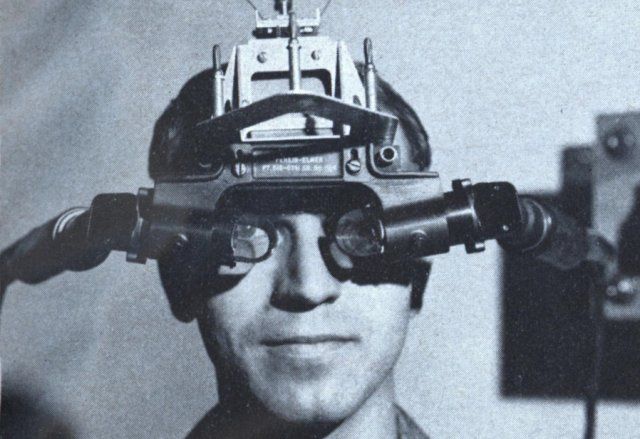

Let’s run an example with augmented reality as the technology and a space launch services company. Despite the (temporary?) demise of Google Glass, augmented reality certainly seems to have the potential to be transformational. It literally changes how we can look at the world! Is it realistic? I would say yes, the technology is almost there, as evidenced by Google Glass and Microsoft HoloLens. Is it actionable? Again, yes. Google Glass was indeed produced. Is it scalable? The infrastructure seems available to support widespread adoption, but the market readiness is a bit of an issue. So yes, but perhaps with qualifications.

With the initial screening done, let’s look at the organizational impact. A space launch company’s leadership knows that due to the unforgiving nature of spaceflight, reliability has to be high. They also know that they need to keep costs low in order to be competitive. Inspection of parts and assembly is expensive but necessary in order to maintain high reliability. With this abbreviated information as the organizational background, it’s time to look at scenarios. This is the “What if?” part of the process. Taking into account the known process areas of the company and the known and projected capabilities of the technology in question, ask “what would happen if we applied this technology?” Don’t forget to try to look for second order effects as well.

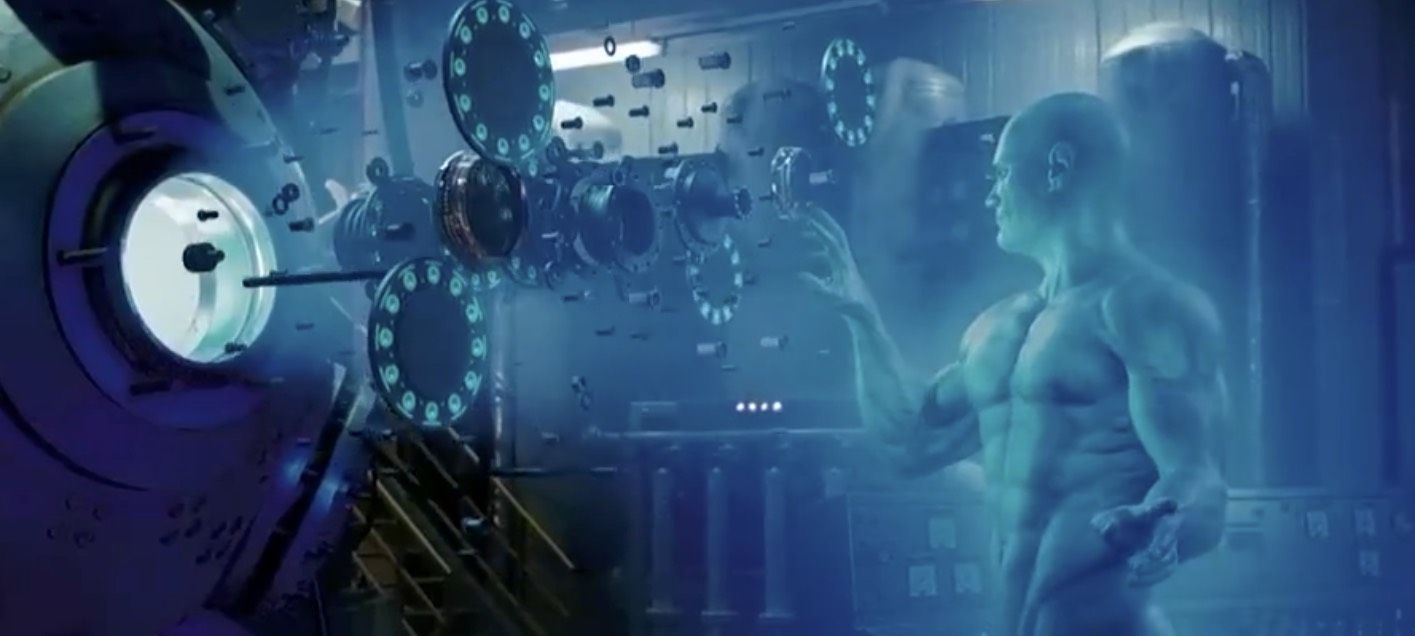

One obvious scenario for the space launch company would be to examine what if augmented reality was used in the inspection and verification process? One could imagine an assembly worker equipped with augmented reality glasses seeing the supply chain history of every part that is being worked on. Perhaps getting artificial intelligence expert guidance during assembly. The immediate effect would be reduced inspection time which equates to cost savings and increased reliability. A second order effect could be greater market share due to a better competitive advantage.

The bottom line is this hypothetical example is that for the space launch company, augmented reality stands a good chance of greatly improving how it does business. It would be a game-changer in at least one area of operations, but wouldn’t completely re-write all the rules.

As the company runs additional scenarios and visualizes the potential, it could determine whether or not this technology is something they want to just wait and see, or be an early adopter, or perhaps directly invest in to bring it along a little bit faster.

The key to all of this is that organizations have to be vigilant in knowing what new technologies and capabilities are on the horizon, and proactive in evaluating how they will be affected by them. If something can be done, it will be done, and if one organization doesn’t use it to create a competitive advantage, rest assured its competitors will.