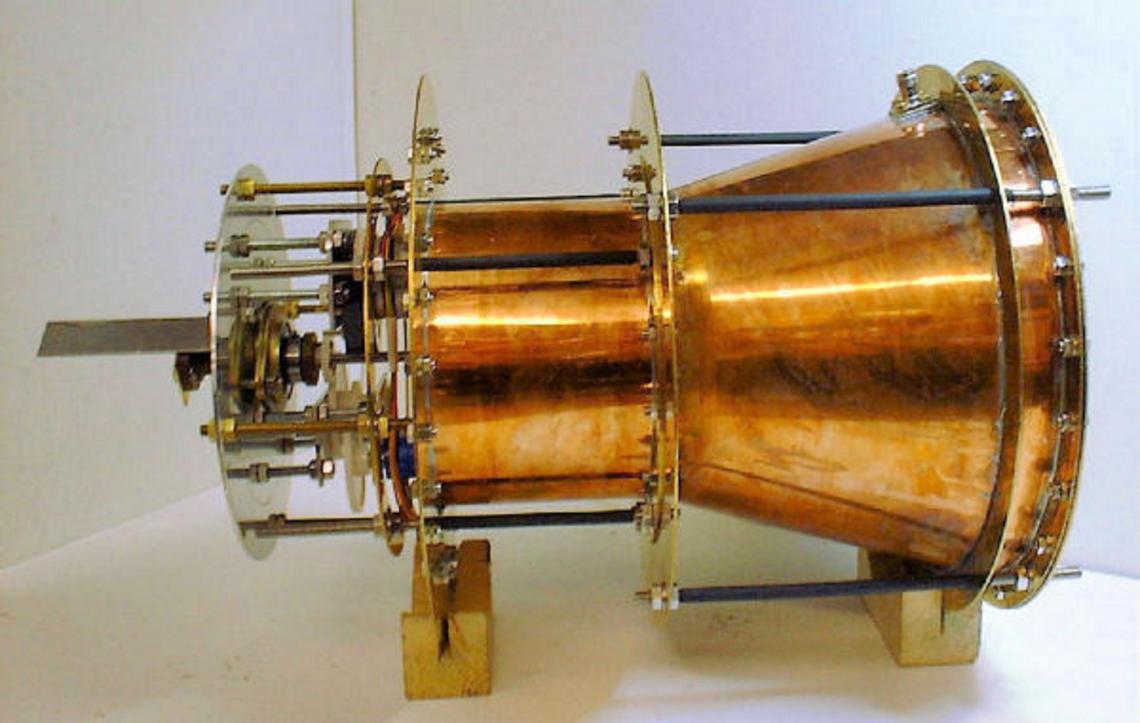

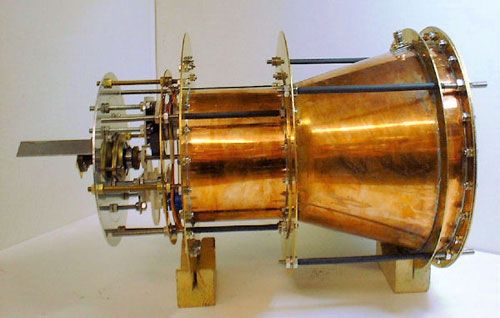

The EMPT thruster, funded by NASA, is a 1 kW-class RMF thruster, operates on the same physics principles as the ELF thruster. This device, less than 4 inches in diameter, has proven that pulsed inductive technolgoies can be succesfully miniaturized. Indeed, this thruster has demonstrated operation from 0.5 to 5 Joules, as well as the first pulsed inductive steady state operation. The EMPT has demonstrated greater than 1E8 continuous plasma discharges.

Category: space travel

NASA, perhaps more than anyone else, knows that there’s only so much room for packing stuff onto a spacecraft. That’s why it’s testing expandable living modules on the International Space Station prior to sending them to Mars for work and living spaces. The Bigelow Expandable Activity Module will ride along in an upcoming SpaceX Dragon resupply mission to the ISS and from there will be unpacked and attached to the side of the station.

After that it’ll be filled with air to expand from just over five feet in depth and almost eight in diameter to 12 feet deep and over 10 feet in diameter and have its pressure equalized with the rest of the station. In the video below, NASA says that it’s all going to be done pretty slowly given that it’s the first experiment of its kind.

The BEAM needs to prove its mettle against cosmic radiation, durability and long-term leak performance prior to going into deep space, however. Before the expandable spaces go near the red planet, they’ll have to survive two years on the ISS with crew members poking and prodding it for the aforementioned reasons. The video below is a rendering, and admittedly moves along much faster than NASA says the installation process will actually go, but it should give you an idea of what the ISS will look like when the bolt-on test module is in place.

Chinese taikonauts will likely beat NASA astronauts back to the lunar surface in as little as five to ten years, longtime lunar scientist and geologist Paul Spudis now tells me. If so, that will happen primarily by default, as the lunar surface continues to drop off NASA’s crewed destination radar.

Of course, that doesn’t preclude Russia, the European Space Agency (ESA), or numerous commercial space ventures — who have all expressed a desire to return astronauts to the lunar surface — from getting there sooner. But for now, Spudis thinks the Chinese are most likely to next make it happen.

Spudis, author of the forthcoming, “The Value of the Moon: How to Explore, Live, and Prosper in Space Using the Moon’s Resources,” emphasizes that he does not object to a “Chinese presence” on the lunar surface. Rather, he objects to the U.S.’ long absence from the lunar surface and what he sees as “our abdication” of responsibility in creating a permanent American presence in cislunar space — the space between the Earth and the Moon. Such a presence, he argues, would guarantee unhindered access to both space commerce and resources available beyond low-Earth orbit (LEO).

The night before the Space Shuttle Challenger was due to lift off, on January 27, 1986, Bob Ebeling tried to talk his boss out of approving the launch. Ebeling was an engineer for a NASA contractor, one of five who worried that the rocket boosters’ “o-rings” might turn brittle in the overnight cold, and that leaking fuel could lead to an explosion. Ebeling’s supervisor refused to stop the launch, and the shuttle exploded the next day, killing 7 astronauts, including a school teacher. A Presidential Commission would later vindicate Ebeling and his colleagues.

Over at NPR, Howard Berkes has written a moving remembrance of Ebeling, who was wracked by guilt for decades. The morning of the launch, Ebeling drove to work to watch the event from a company conference room. He was accompanied by his daughter:

“He said, ‘The Challenger’s going to blow up. Everyone’s going to die,’” [she recalled.] “And he was beating his fist on the dashboard. He was frantic.”

A lot of focus over the past 12 months has been on NASA’s journey to Mars. But a group of space experts, including leading NASA scientists, has now produced a special journal edition that details how we could establish a human colony on the Moon in the next seven years — all for US$10 billion.

Although that’s pretty awesome, the goal isn’t really the Moon itself — from an exploratory point of view, most scientists have bigger targets in sight. But the lessons we’ll learn and the technology we’ll develop building a human base outside of Earth will eventually be the key to colonising Mars, and other planets, according to the experts.

“My interest is not the Moon. To me the Moon is as dull as a ball of concrete,” NASA astrobiologist Chris McKay, who edited the special, open-access issue of New Space journal, told Sarah Fecht over at Popular Science. “But we’re not going to have a research base on Mars until we can learn how to do it on the Moon first. The Moon provides a blueprint to Mars.”