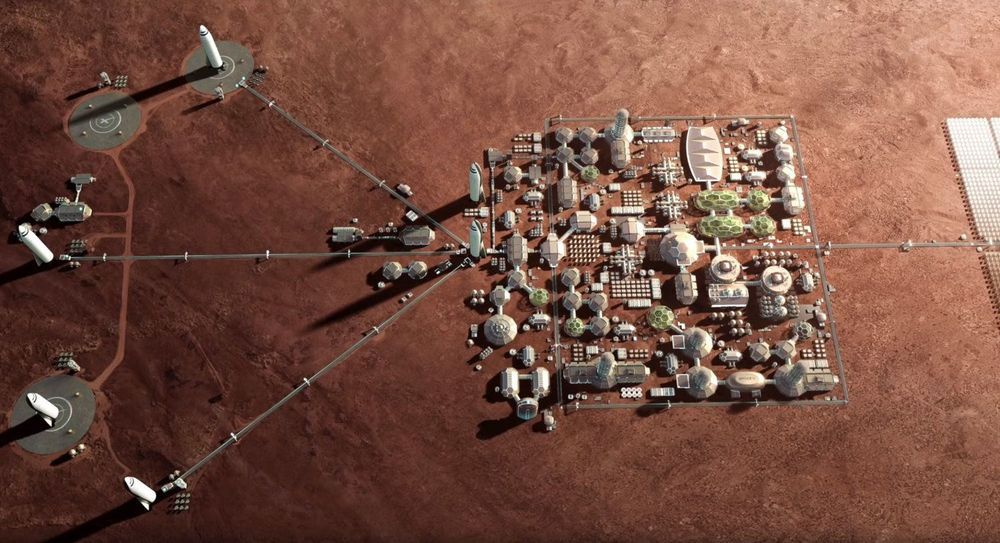

The holidays might be a time of slowed activity for most companies in the tech sector, but for SpaceX, it was a time to ramp production efforts on the latest Starship prototype — “Starship SN1” as it’s called, according to SpaceX CEO Elon Musk. This flight design prototype of Starship is under construction at SpaceX’s Boca Chica, Texas development facility, and Musk was in attendance over the weekend overseeing its build and assembly.

Musk shared video of the SpaceX team working on producing the curved dome that will sit atop the completed Starship SN1 (likely stands for “serial number 1,” a move to a more iterative naming system and away from the “Mark” nomenclature used for the original prototype), a part he called “the most difficult” in terms of the main components of the new spacecraft. He added that each new SN version of the rocket SpaceX builds will have minor improvements “at least” through the first 20 or so versions, so it’s clear they expect to iterate and test these quickly.

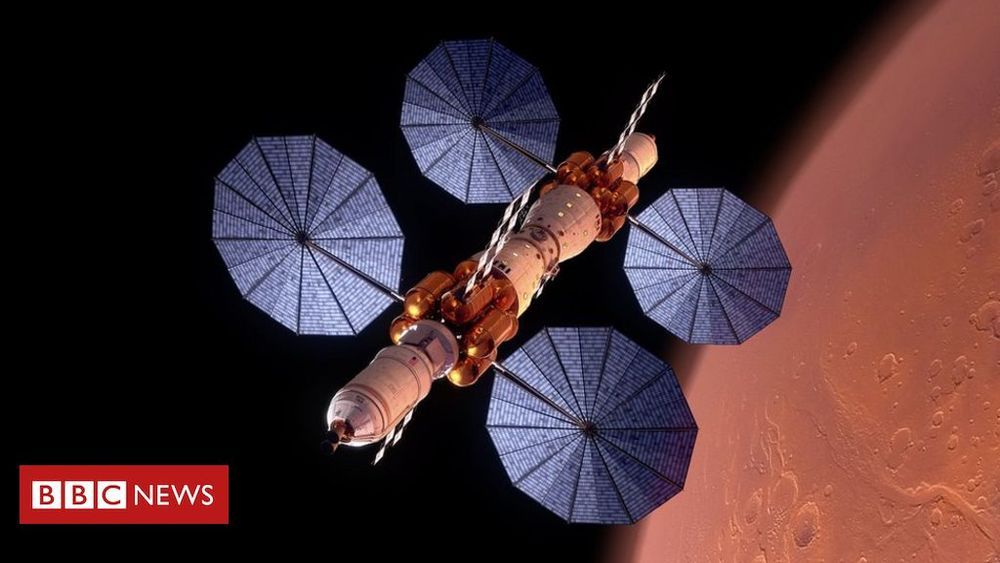

As for when it might actually fly, Musk said that he hopes this Starship will take off sometime around “2 to 3 months” from now, which is still within range of the projections for a first Starship high-altitude test flight given by the CEO earlier this year at the unveiling of the Starship Mk1 prototype. That prototype was originally positioned as the one that would fly for the high-altitude test, but it blew its top during testing in November and Musk said they’d be moving on to a new design rather than repair or rebuild the Mk1.