A team of researchers from Jülich in cooperation with the University of Magdeburg has developed a new method to measure the electric potentials of a sample at atomic accuracy. Using conventional methods, it was virtually impossible until now to quantitatively record the electric potentials that occur in the immediate vicinity of individual molecules or atoms. The new scanning quantum dot microscopy method, which was recently presented in the journal Nature Materials by scientists from Forschungszentrum Jülich together with partners from two other institutions, could open up new opportunities for chip manufacture or the characterization of biomolecules such as DNA.

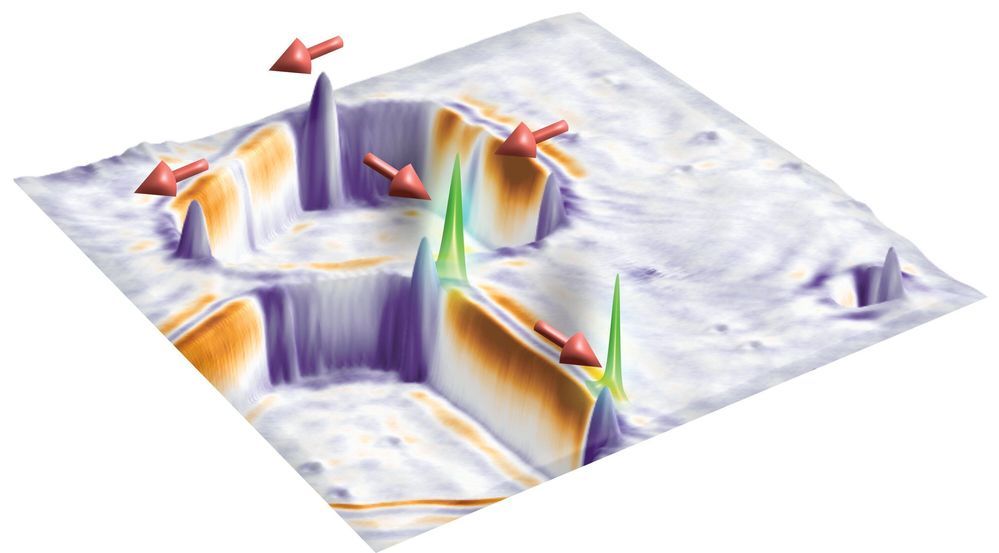

The positive atomic nuclei and negative electrons of which all matter consists produce electric potential fields that superpose and compensate each other, even over very short distances. Conventional methods do not permit quantitative measurements of these small-area fields, which are responsible for many material properties and functions on the nanoscale. Almost all established methods capable of imaging such potentials are based on the measurement of forces that are caused by electric charges. Yet these forces are difficult to distinguish from other forces that occur on the nanoscale, which prevents quantitative measurements.

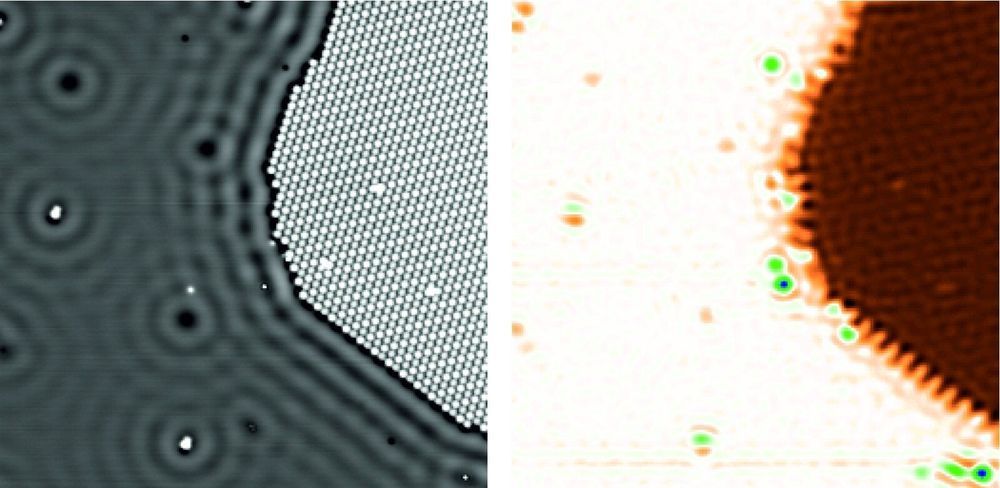

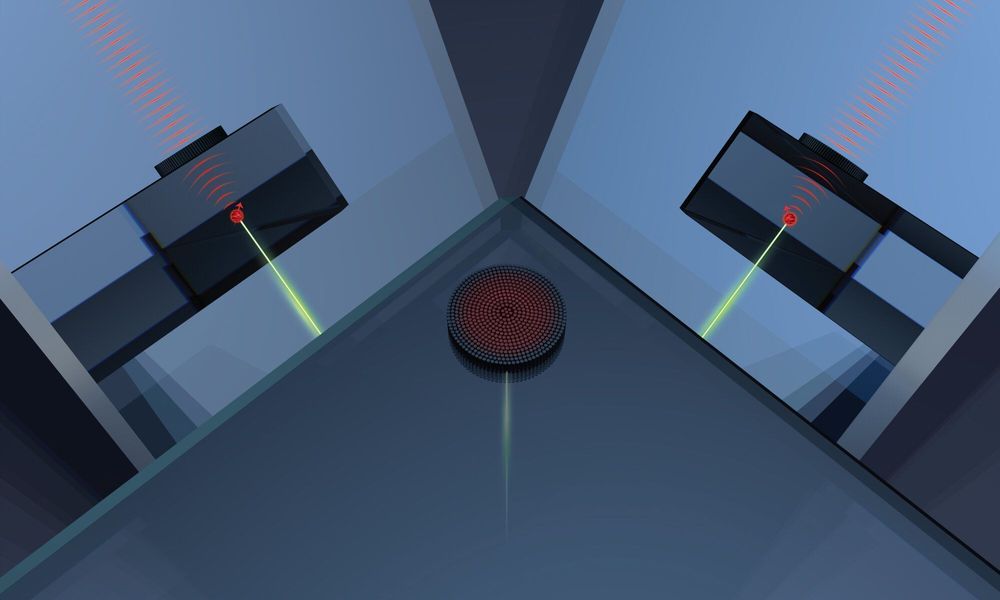

Four years ago, however, scientists from Forschungszentrum Jülich discovered a method based on a completely different principle. Scanning quantum dot microscopy involves attaching a single organic molecule—the quantum dot—to the tip of an atomic force microscope. This molecule then serves as a probe. “The molecule is so small that we can attach individual electrons from the tip of the atomic force microscope to the molecule in a controlled manner,” explains Dr. Christian Wagner, head of the Controlled Mechanical Manipulation of Molecules group at Jülich’s Peter Grünberg Institute (PGI-3).