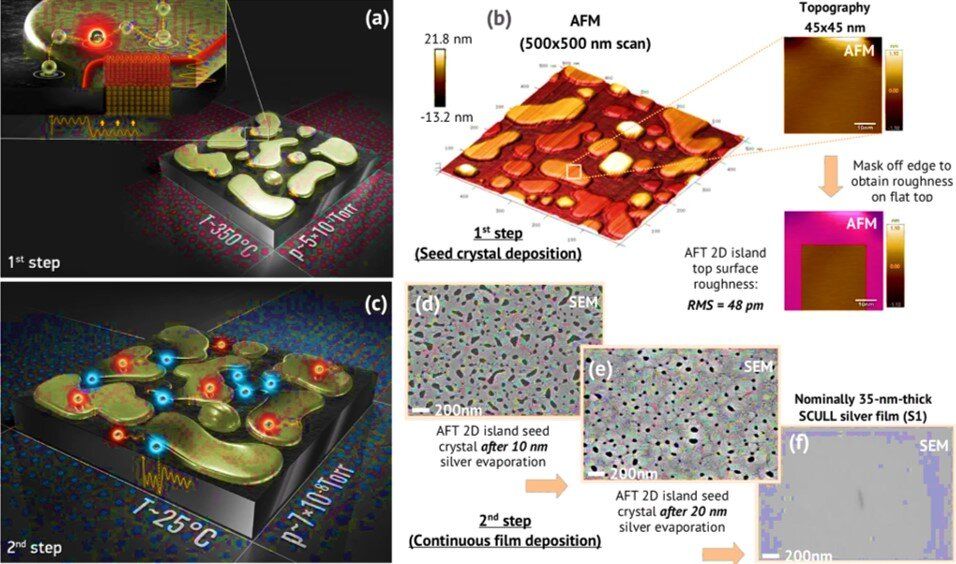

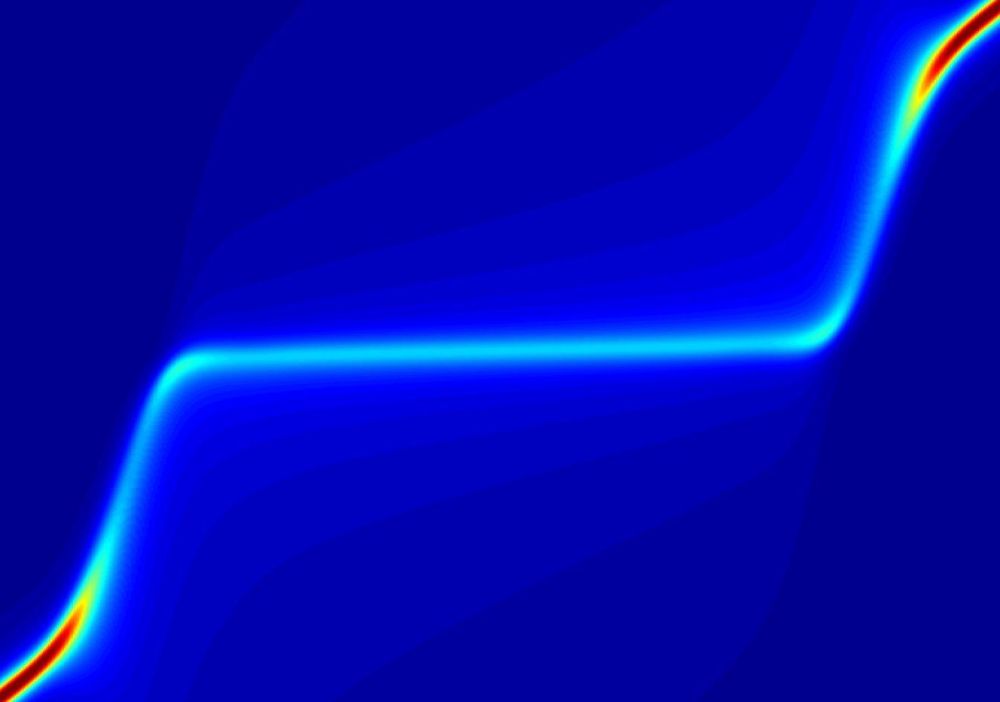

Ultra-low-loss metal films with high-quality single crystals are in demand as the perfect surface for nanophotonics and quantum information processing applications. Silver is by far the most preferred material due to low-loss at optical and near infrared (near-IR) frequencies. In a recent study now published on Scientific Reports, Ilya A. Rodionov and an interdisciplinary research team in Germany and Russia reported a two-step approach for electronic beam evaporation of atomically smooth single crystalline metal films. They proposed a method to establish thermodynamic control of the film growth kinetics at the atomic level in order to deposit state-of-the-art metal films.

The researchers deposited 35 to 100 nm thick, single-crystalline silver films with sub-100 picometer (pm) surface roughness with theoretically limited optical losses to form ultrahigh-Q nanophotonic devices. They experimentally estimated the contribution of material purity, material grain boundaries, surface roughness and crystallinity to the optical properties of metal films. The team demonstrated a fundamental two-step approach for single-crystalline growth of silver, gold and aluminum films to open new possibilities in nanophotonics, biotechnology and superconductive quantum technologies. The research team intends to adopt the method to synthesize other extremely low-loss single-crystalline metal films.

Optoelectronic devices with plasmonic effects for near-field manipulation, amplification and sub-wavelength integration can open new frontiers in nanophotonics, quantum optics and in quantum information. Yet, the ohmic losses associated in metals are a considerable challenge to develop a variety of useful plasmonic devices. Materials scientists have devoted research efforts to clarify the influence of metal film properties to develop high performance material platforms. Single-crystalline platforms and nanoscale structural alterations can prevent this problem by eliminating material-induced scattering losses. While silver is one of the best known plasmonic metals at optical and near-IR frequencies, the metal can be challenging for single-crystalline film growth.