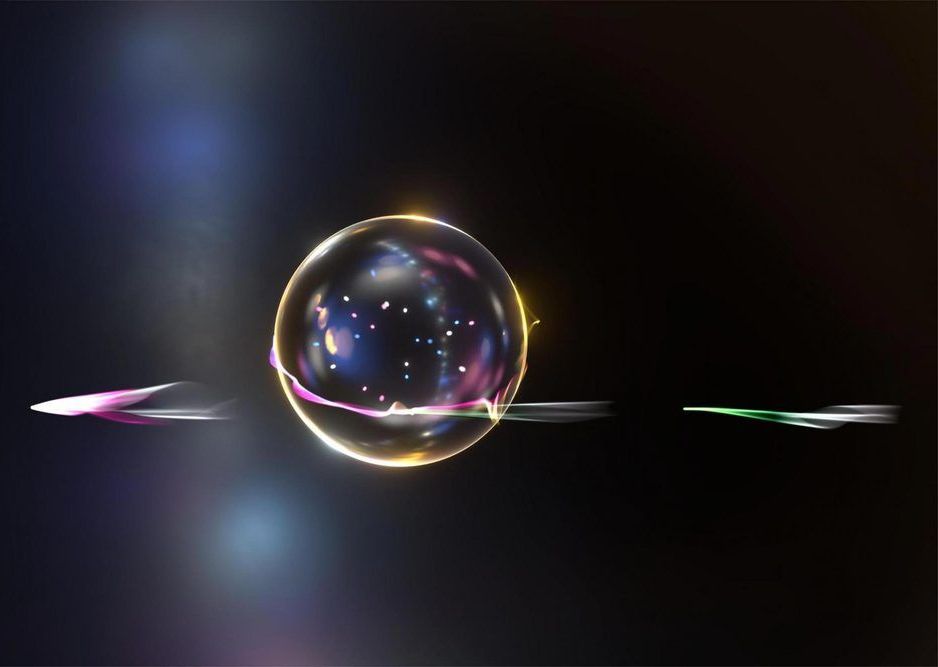

Researchers from the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, joined by a colleague from Argonne National Laboratory, U.S., have implemented an advanced quantum algorithm for measuring physical quantities using simple optical tools. Published in Scientific Reports, their study takes us a step closer to affordable linear optics-based sensors with high performance characteristics. Such tools are sought after in diverse research fields, from astronomy to biology.

Maximizing the sensitivity of measurement tools is crucial for any field of science and technology. Astronomers seek to detect remote cosmic phenomena, biologists need to discern exceedingly tiny organic structures, and engineers have to measure the positions and velocities of objects, to name a few examples.

Until recently, no measurement tool could ensure precision above the so-called shot noise limit, which has to do with the statistical features inherent in classical observations. Quantum technology has provided a way around this, boosting precision to the fundamental Heisenberg limit, stemming from the basic principles of quantum mechanics. The LIGO experiment, which detected gravitational waves for the first time in 2016, shows it is possible to achieve Heisenberg-limited sensitivity by combining complex optical interference schemes and quantum techniques.