Ultracold atoms trapped in appropriately prepared optical traps can arrange themselves in surprisingly complex, hitherto unobserved structures, according to scientists from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Cracow. In line with their most recent predictions, matter in optical lattices should form tensile and inhomogeneous quantum rings in a controlled manner.

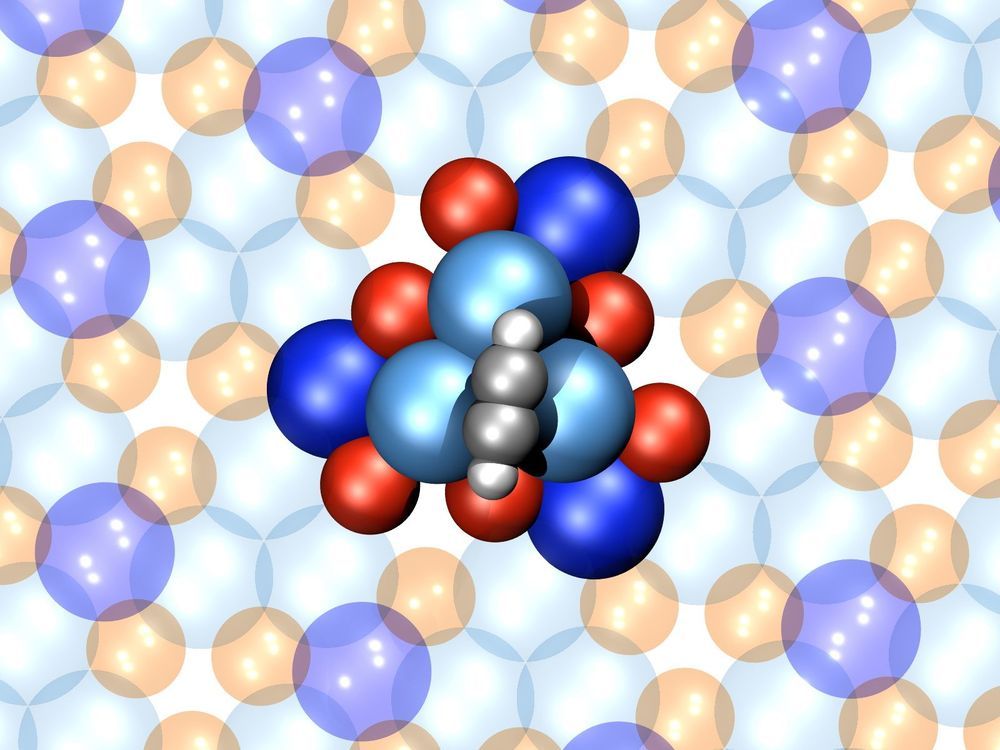

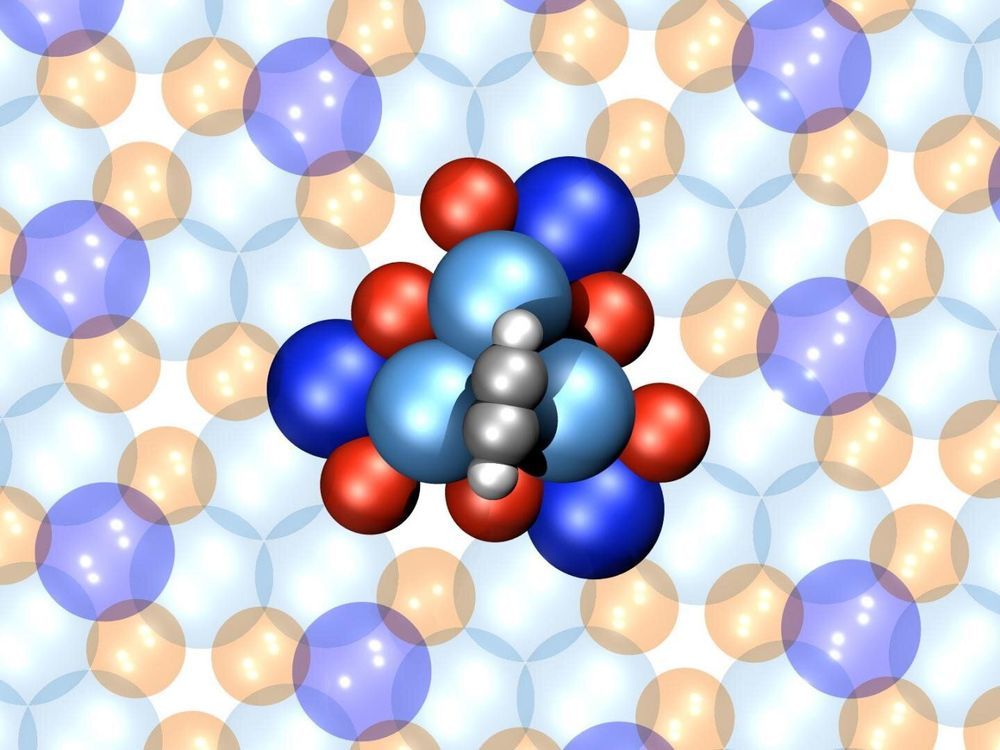

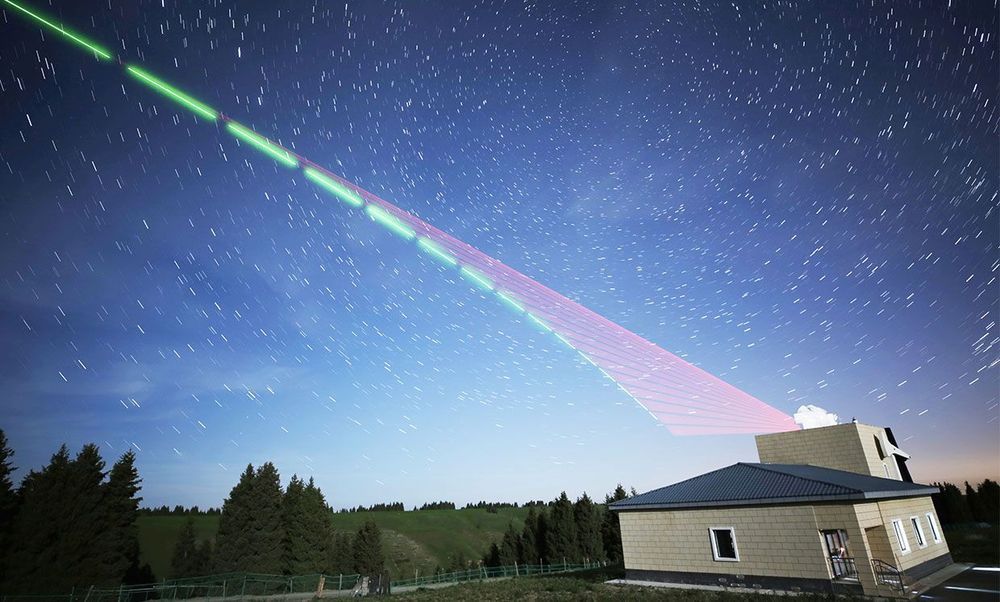

An optical lattice is a structure built of light, i.e. electromagnetic waves. Lasers play a key role in the construction of such lattices. Each laser generates an electromagnetic wave with strictly defined, constant parameters which can be almost arbitrary modified. When the laser beams are matched properly, it is possible to create a lattice with well known properties. By overlapping of waves, the minima of potential can be obtained, whose arrangement enables simulation of the systems and models well-known from solid state physics. The advantage of such prepared systems is the relatively simple way to modify positions of these minima, what in practice means the possibility of preparing various type of lattices.

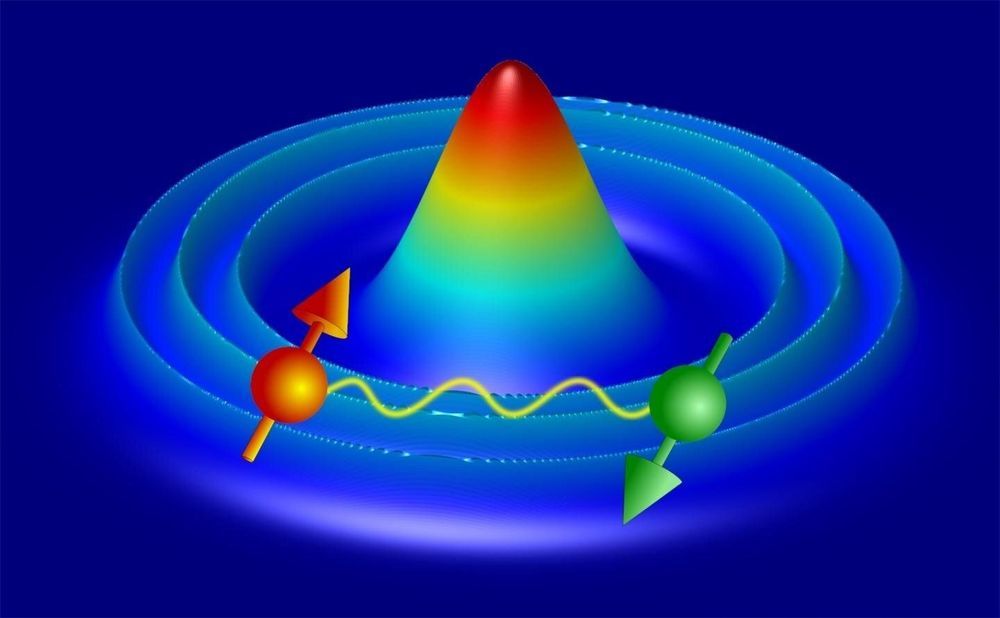

“If we introduce appropriately selected atoms into an area of space that has been prepared in this way, they will congregate in the locations of potential minima. However, there is an important condition: the atoms must be cooled to ultra-low temperatures. Only then will their energy be small enough not to break out of the subtle prepared trap,” explains Dr. Andrzej Ptok from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IFJ PAN) in Cracow.