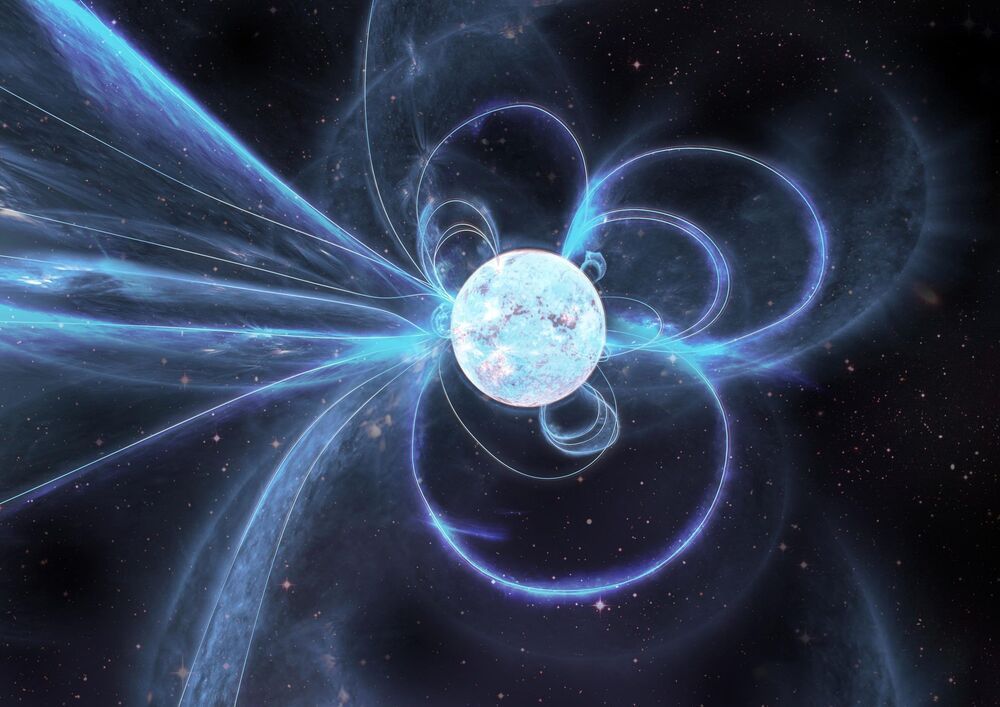

Astronomers from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav) and CSIRO have just observed bizarre, never-seen-before behavior from a ‘radio-loud’ magnetar—a rare type of neutron star and one of the strongest magnets in the Universe.

Their new findings, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS), suggest magnetars have more complex magnetic fields than previously thought – which may challenge theories of how they are born and evolve over time.

Magnetars are a rare type of rotating neutron star with some of the most powerful magnetic fields in the Universe. Astronomers have detected only thirty of these objects in and around the Milky Way —most of them detected by X-ray telescopes following a high-energy outburst.