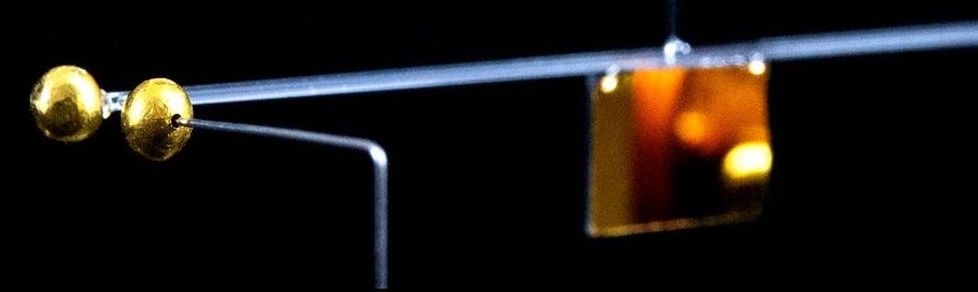

The smallest-scale measurements of gravity ever made show that a tiny gold ball weighing 90 milligrams can move another gold ball just a few nanometres through gravitational pull.

Scientists have taken a major step forward in harnessing machine learning to accelerate the design for better batteries: Instead of using it just to speed up scientific analysis by looking for patterns in data, as researchers generally do, they combined it with knowledge gained from experiments and equations guided by physics to discover and explain a process that shortens the lifetimes of fast-charging lithium-ion batteries.

It was the first time this approach, known as “scientific machine learning,” has been applied to battery cycling, said Will Chueh, an associate professor at Stanford University and investigator with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory who led the study. He said the results overturn long-held assumptions about how lithium-ion batteries charge and discharge and give researchers a new set of rules for engineering longer-lasting batteries.

The research, reported today in Nature Materials, is the latest result from a collaboration between Stanford, SLAC, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Toyota Research Institute (TRI). The goal is to bring together foundational research and industry know-how to develop a long-lived electric vehicle battery that can be charged in 10 minutes.

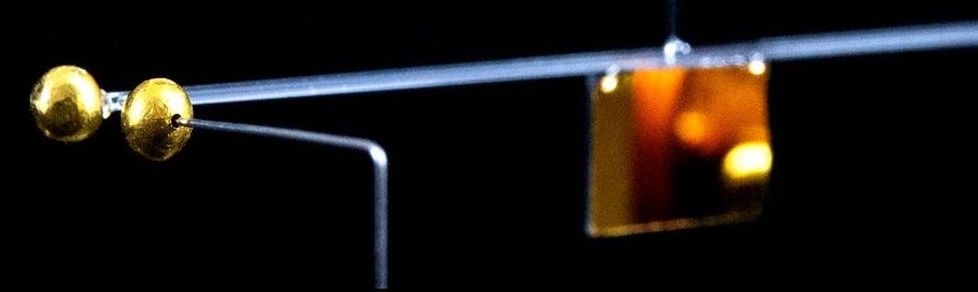

How can you possibly use simulations to reconstruct the history of the entire universe using only a small sample of galaxy observations? Through big data, that’s how.

Theoretically, we understand a lot of the physics of the history and evolution of the universe. We know that the universe used to be a lot smaller, denser, and hotter in the past. We know that its expansion is accelerating today. We know that the universe is made of very different things, including galaxies (which we can see) and dark matter (which we can’t).

We know that the largest structures in the universe have evolved slowly over time, starting as just small seeds and building up over billions of years through gravitational attraction.

Astronomers have detected the best place and time to live in the Milky Way, in a recent study published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

More than six billion years ago, the outskirts of the Milky Way were the safest places for the development of possible life forms, sheltered from the most violent explosions in the universe, that is, the gamma-ray bursts and supernovae.

Also read: Astronomers discover new exoplanet instrumental in hunt for traces of life beyond solar system.

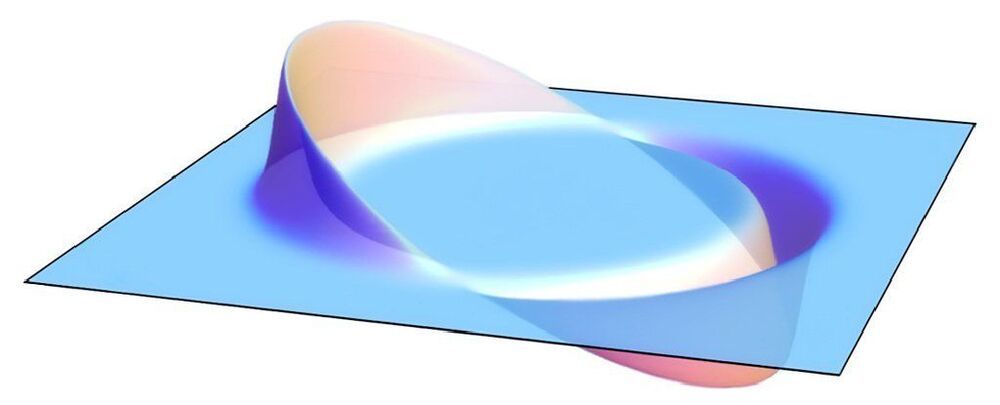

The idea of a warp drive taking us across large areas of space faster than the speed of light has long fascinated scientists and sci-fi fans alike. While we’re still a very long way from jumping any universal speed limits, that doesn’t mean we’ll never ride the waves of warped space-time.

Now a group of physicists have put together the first proposal for a physical warp drive, based on a concept devised back in the ’90s. And they say it shouldn’t break any of laws of physics.

Theoretically speaking, warp drives bend and change the shape of space-time to exaggerate differences in time and distance that, under some circumstances, could see travelers move across distances faster than the speed of light.

😃

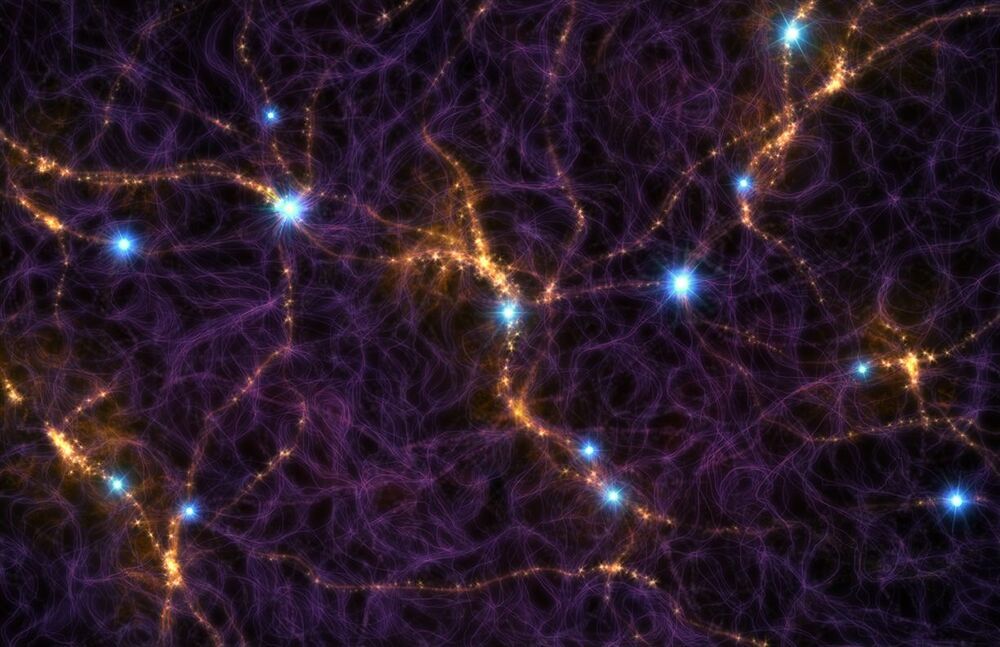

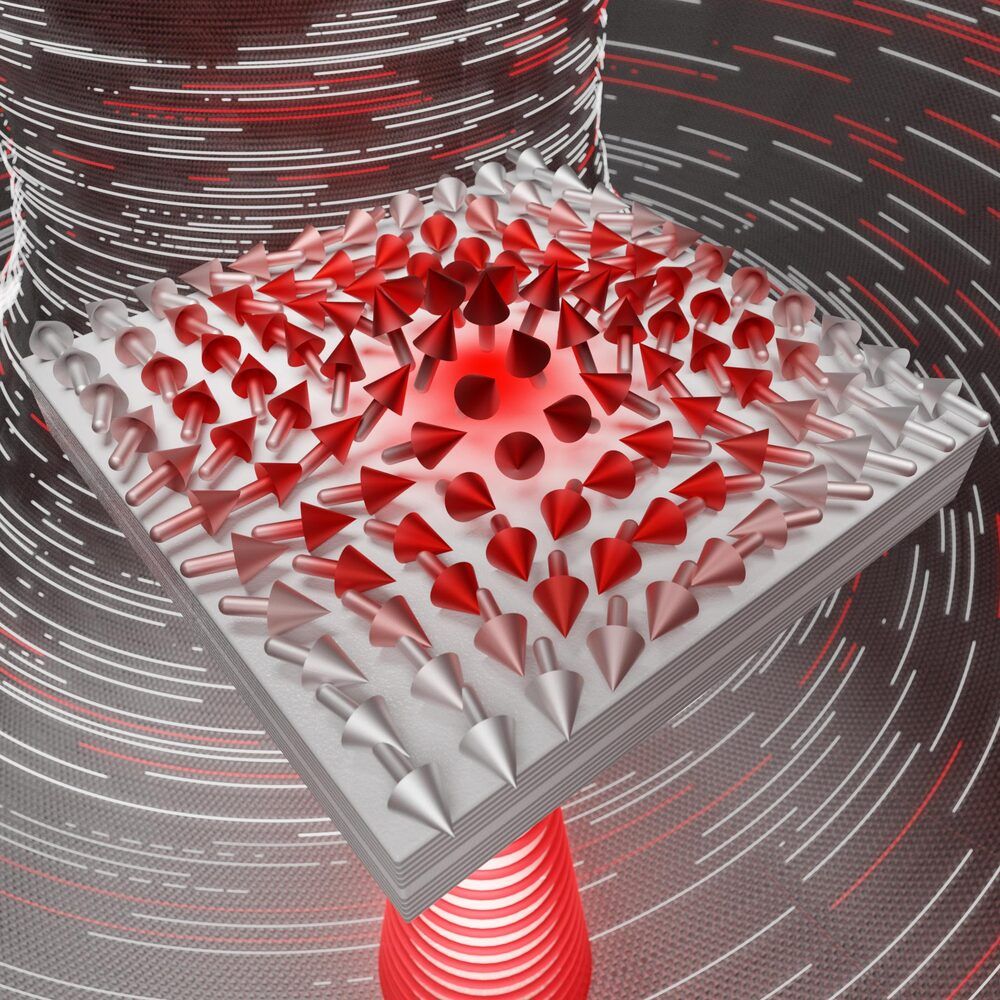

Scientists have demonstrated how to structure light such that its polarization behaves like a collective of spins in a ferromagnet forming half-skyrmions (also known as merons). To achieve this, the light was trapped in a thin liquid crystal layer between two nearly perfect mirrors. Skyrmions, in general, are found, e.g., as elementary excitations of magnetization in a two-dimensional ferromagnet but do not naturally appear in electromagnetic (light) fields.

One of the key concepts in physics, and science overall, is the notion of a “field” that can describe the spatial distribution of a physical quantity. For instance, a weather map shows the distributions of temperature and pressure (these are known as scalar fields), as well as the wind speed and direction (known as a vector field). Almost everyone wears a vector field on their head — every hair has an origin and an end, just like a vector. Over 100 years ago L.E.J. Brouwer proved the hairy ball theorem which states that you can’t comb a hairy ball flat without creating whorls, whirls (vortices), or cowlicks.

Previous ideas about how to make these hypothetical devices have required exotic forms of matter and energy that may not exist, but a new idea for a warp drive that doesn’t break the laws of physics may be theoretically possible. However, it may not be practical in the foreseeable future because it requires ultra dense materials.