It’s exotic, incredibly cold stuff.

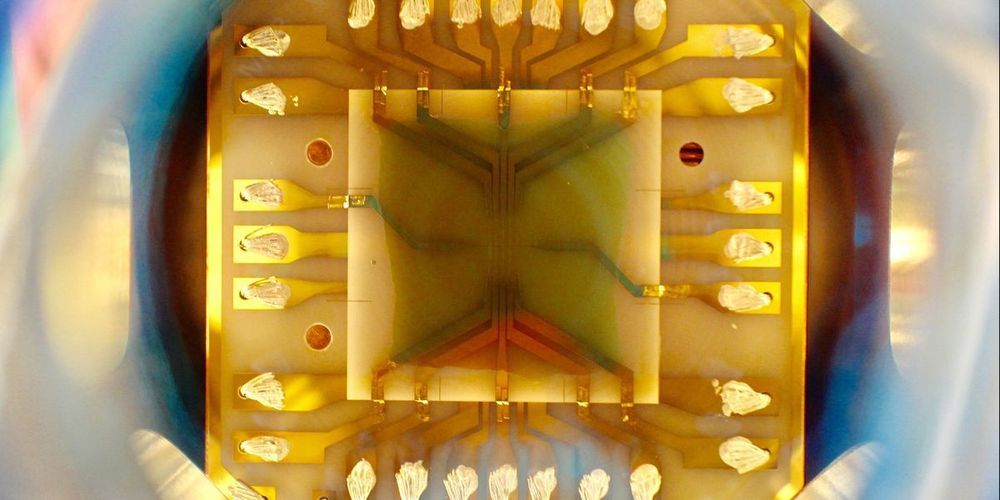

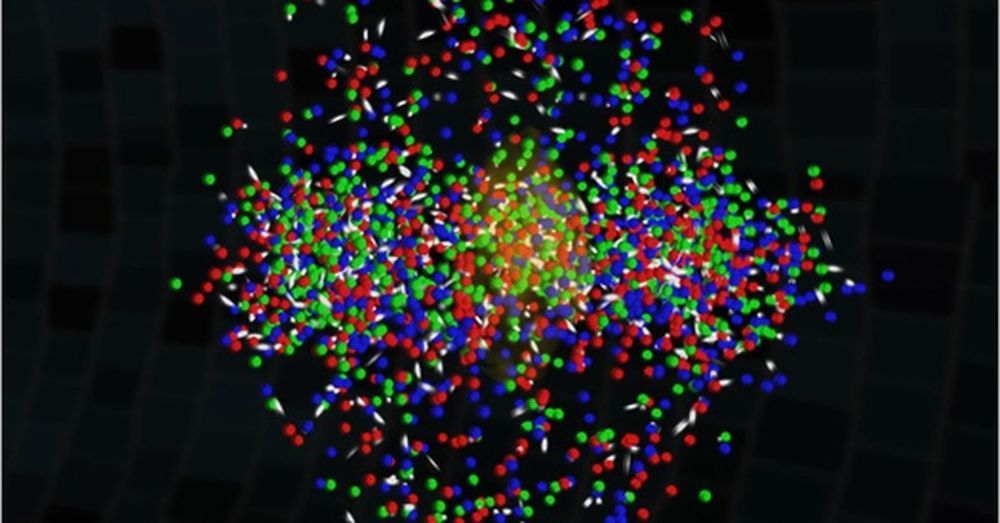

Patrick Windpassinger and his team demonstrate how light stored in a cloud of ultra-cold atoms can be transported by means of an optical conveyor belt.

A team of physicists led by Professor Patrick Windpassinger at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) has successfully transported light stored in a quantum memory over a distance of 1.2 millimeters. They have demonstrated that the controlled transport process and its dynamics has only little impact on the properties of the stored light. The researchers used ultra-cold rubidium-87 atoms as a storage medium for the light as to achieve a high level of storage efficiency and a long lifetime.

“We stored the light by putting it in a suitcase so to speak, only that in our case the suitcase was made of a cloud of cold atoms. We moved this suitcase over a short distance and then took the light out again. This is very interesting not only for physics in general, but also for quantum communication, because light is not very easy to ‘capture’, and if you want to transport it elsewhere in a controlled manner, it usually ends up being lost,” said Professor Patrick Windpassinger, explaining the complicated process.

We stored the light by putting it in a suitcase so to speak, only that in our case the suitcase was made of a cloud of cold atoms,” says physicist Patrick Windpassinger from Mainz University in Germany. “We moved this suitcase over a short distance and then took the light out again.

The storage and transfer of information is a fundamental part of any computing system, and quantum computing systems are no different – if we’re going to benefit from the speed and security of quantum computers and a quantum internet, then we need to figure out how to shift quantum data around.

One of the ways scientists are approaching this is through optical quantum memory, or using light to store data as maps of particle states, and a new study reports on what researchers are calling a milestone in the field: the successful storage and transfer of light using quantum memory.

The researchers weren’t able to transfer the light very far – just 1.2 millimetres or 0.05 inches – but the process outlined here could form the foundation of the quantum-powered computers and communication systems of the future.

“Whenever we have developed better clocks, we’ve learned something new about the world,” said Alexander Smith, an assistant professor of physics at Saint Anselm College and adjunct assistant professor at Dartmouth College, who led the research as a junior fellow in Dartmouth’s Society of Fellows. “Quantum time dilation is a consequence of both quantum mechanics and Einstein’s relativity, and thus offers a new possibility to test fundamental physics at their intersection.”

A phenomenon of quantum mechanics known as superposition can impact timekeeping in high-precision clocks, according to a theoretical study from Dartmouth College, Saint Anselm College and Santa Clara University.

Research describing the effect shows that superposition — the ability of an atom to exist in more than one state at the same time — leads to a correction in atomic clocks known as “quantum time dilation.”

The research, published today (October 23, 2020) in the journal Nature Communications, takes into account quantum effects beyond Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity to make a new prediction about the nature of time.

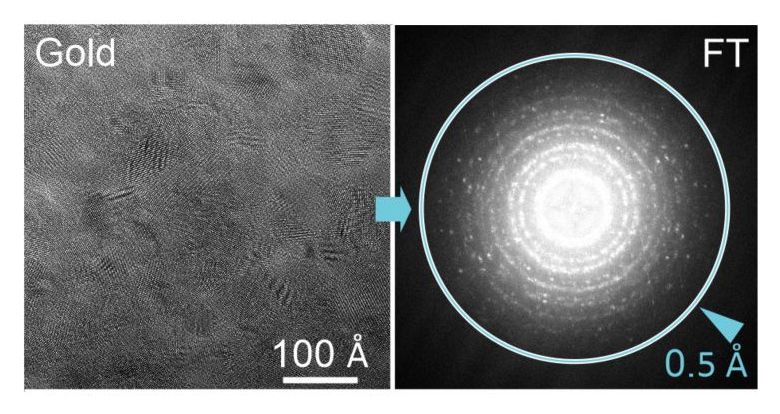

Optical clocks are so accurate that it would take an estimated 20 billion years—longer than the age of the universe—to lose or gain a second. Now, researchers in the U.S. led by Jun Ye’s group at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the University of Colorado have exploited the precision and accuracy of their optical clock and the unprecedented stability of their crystalline silicon optical cavity to tighten the constraints on any possible coupling between particles and fields in the standard model of physics and the so-far elusive components of dark matter.

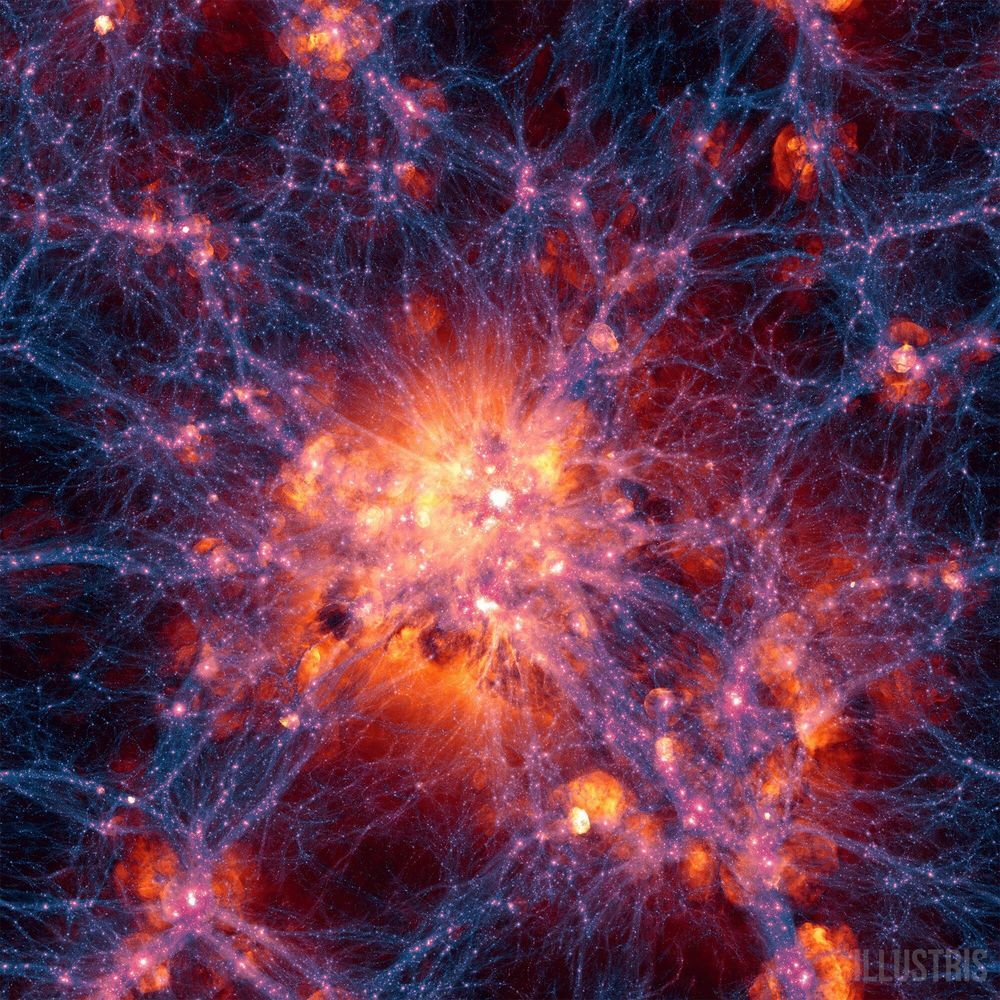

The existence of dark matter is indirectly evident from gravitational effects at galactic and cosmological scales, but beyond that, little is known of its nature. One of the effects that falls out of theoretical analysis of dark matter coupling to particles in the standard model of physics is a resulting oscillation in fundamental constants. Ye and collaborators figured that if their world-class metrology equipment could not detect these oscillations, then this apparently null result would be useful confirmation that the strength of dark matter interactions with particles in the standard model of physics must be even lower than dictated by the constraints so far on record.

Circa 2010

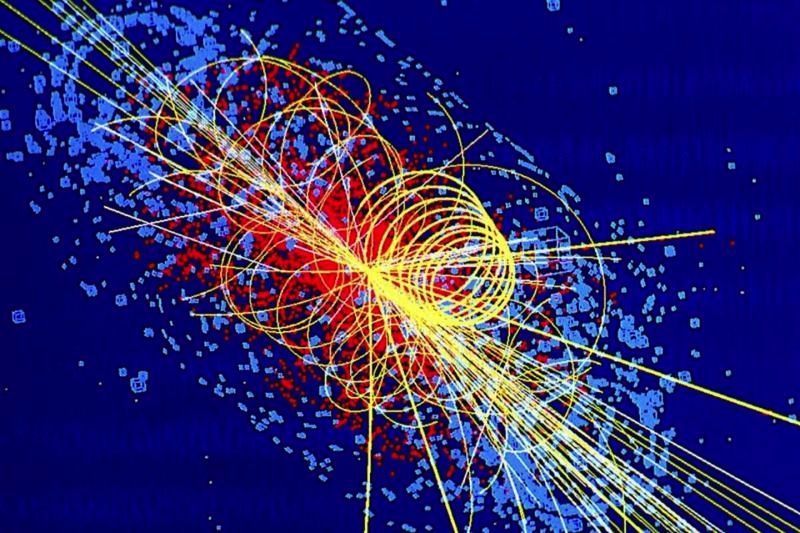

Until the LHC finally gets up to full speed, Brookhaven National Lab’s Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) remains the world’s most powerful heavy ion smasher. And on Monday, they showed off some of that power by announcing that a recent collision resulted in the hottest matter ever recorded. Coming in at a scorching 7.2 trillion degrees Fahrenheit, the plasma not only recreated the environment of the Big Bang, but might have also resulted in the temporary formation of a bubble within which some normal laws of physics did not apply.