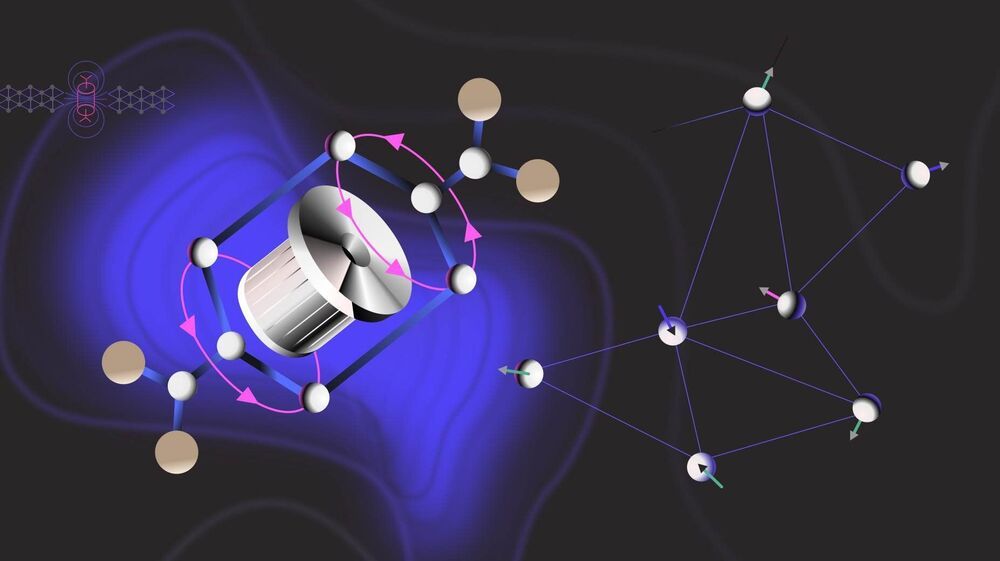

We probably think we know gravity pretty well. After all, we have more conscious experience with this fundamental force than with any of the others (electromagnetism and the weak and strong nuclear forces). But even though physicists have been studying gravity for hundreds of years, it remains a source of mystery.

In our video Why Is Gravity Different? We explore why this force is so perplexing and why it remains difficult to understand how Einstein’s general theory of relativity (which covers gravity) fits together with quantum mechanics.

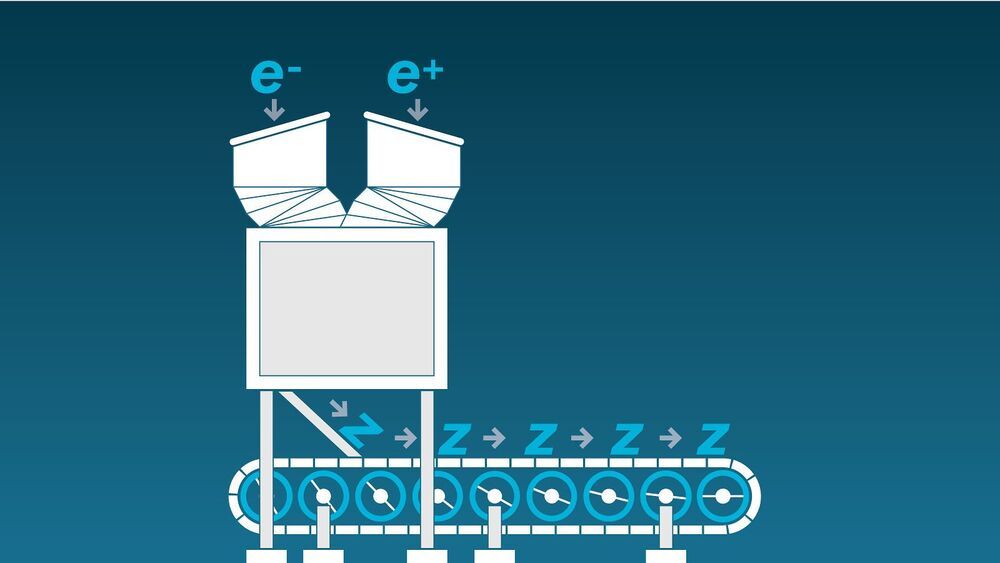

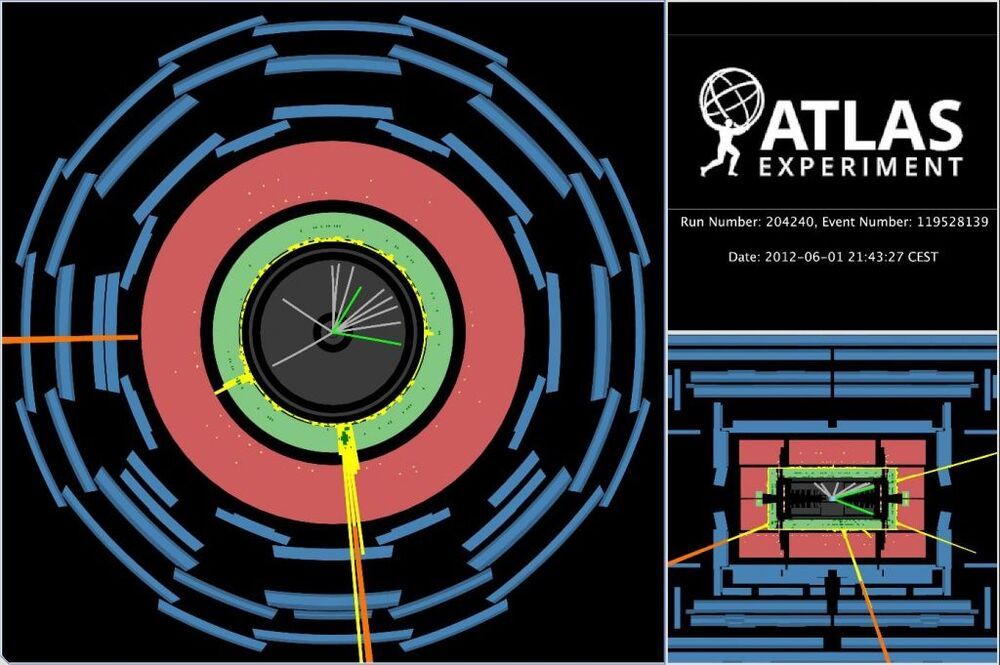

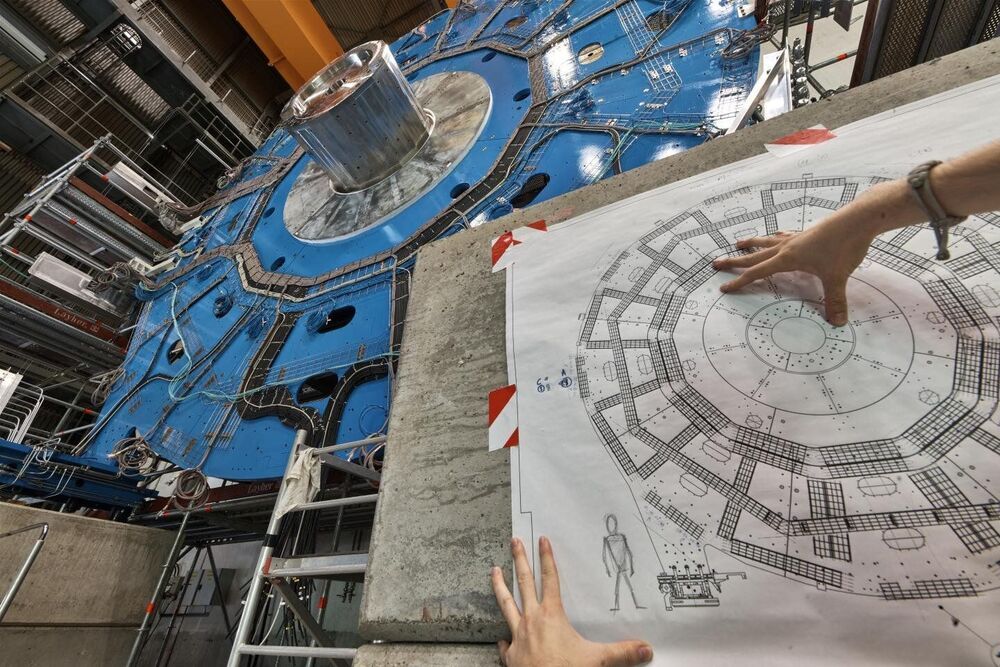

Gravity is extraordinarily weak and nearly impossible to study directly at the quantum level. We cannot scrutinize it using particle accelerators like we can with the other forces, so we need other ways to get at quantum gravity.