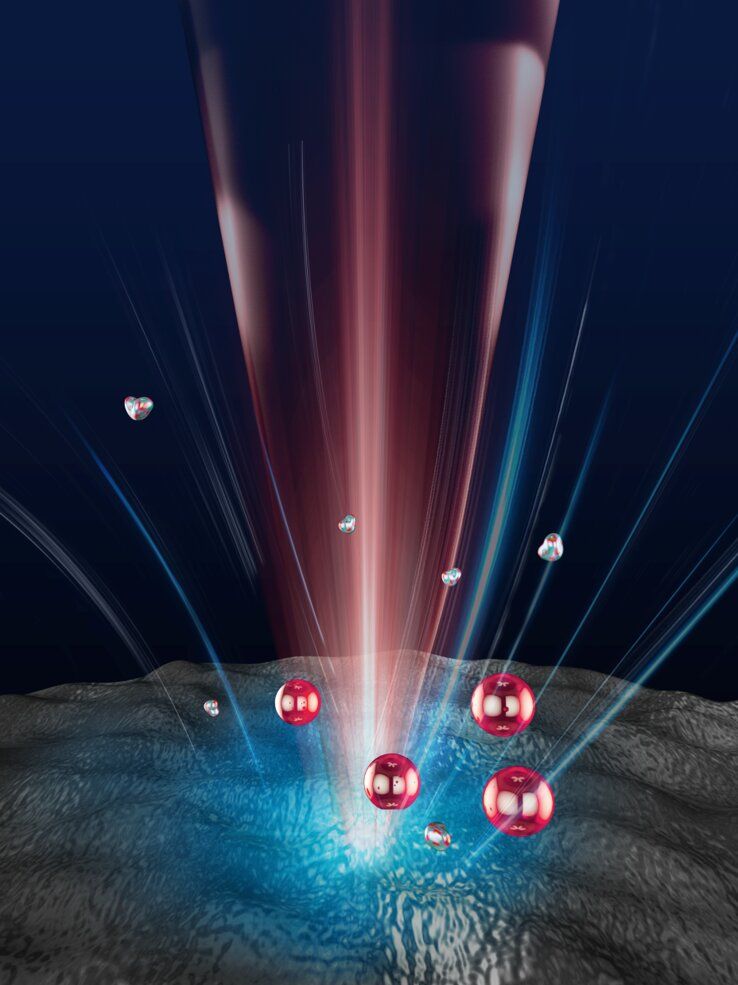

Finding the hypothetical particle axion could mean finding out for the first time what happened in the Universe a second after the Big Bang, suggests a new study published in Physical Review D.

How far back into the Universe’s past can we look today? In the electromagnetic spectrum, observations of the Cosmic Microwave Background — commonly referred to as the CMB — allow us to see back almost 14 billion years to when the Universe cooled sufficiently for protons and electrons to combine and form neutral hydrogen. The CMB has taught us an inordinate amount about the evolution of the cosmos, but photons in the CMB were released 400000 years after the Big Bang making it extremely challenging to learn about the history of the universe prior to this epoch.

To open a new window, a trio of theoretical researchers, including Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU) Principal Investigator, University of California, Berkeley, MacAdams Professor of Physics and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory senior faculty scientist Hitoshi Murayama, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory physics researcher and University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral fellow Jeff Dror (now at University of California, Santa Cruz), and UC Berkeley Miller Research Fellow Nicholas Rodd, looked beyond photons, and into the realm of hypothetical particles known as axions, which may have been emitted in the first second of the Universe’s history.