Nice read that ties Quantum properties such as tunneling to everything around us including our own blood supply in our bodies.

Objects of the quantum world are of a concealed and cold-blooded nature: they usually behave in a quantum manner only when they are significantly cooled and isolated from the environment. Experiments carried out by chemists and physicists from Warsaw have destroyed this simple picture. It turns out that not only does one of the most interesting quantum effects occur at room temperature and higher, but it plays a dominant role in the course of chemical reactions in solutions!

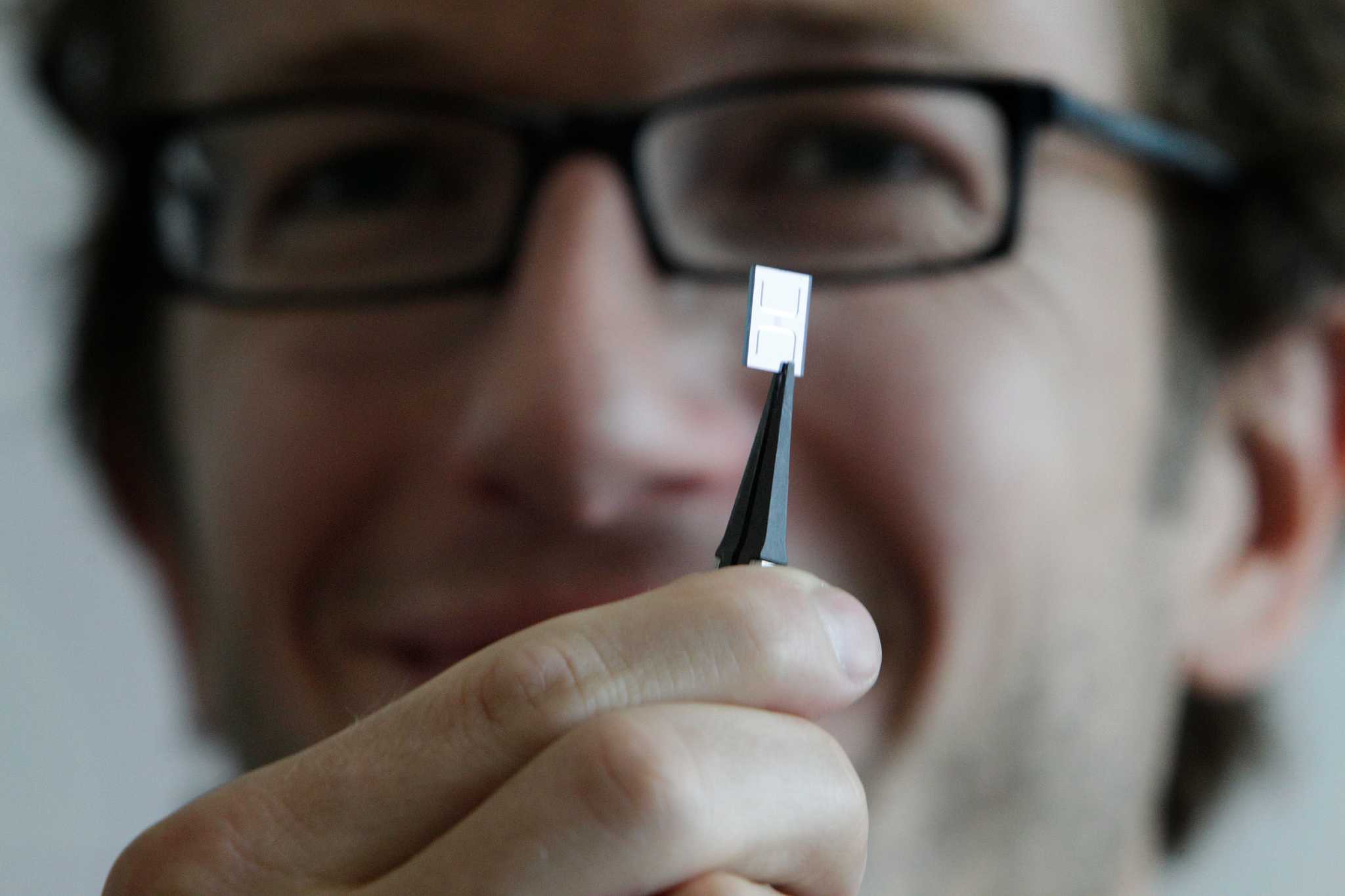

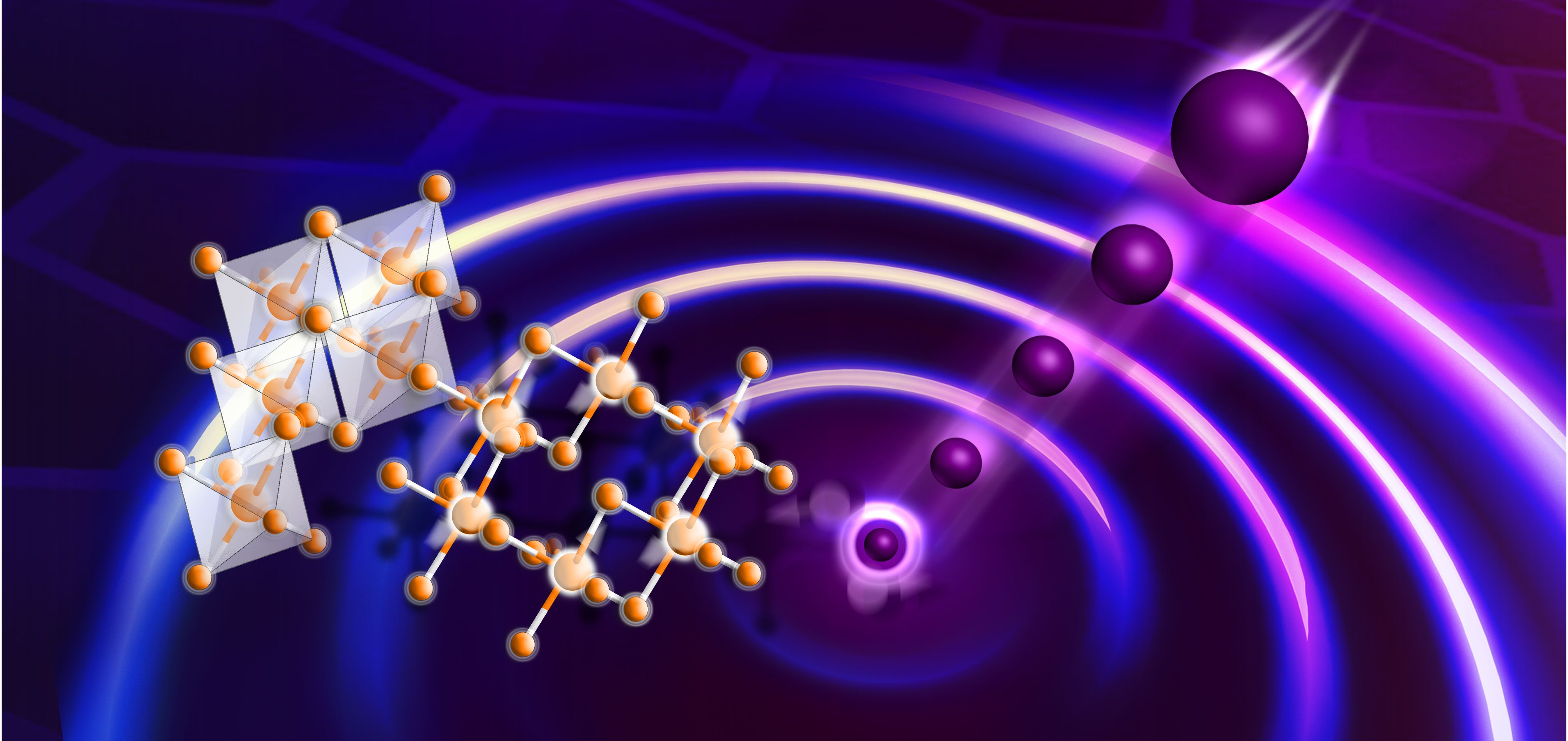

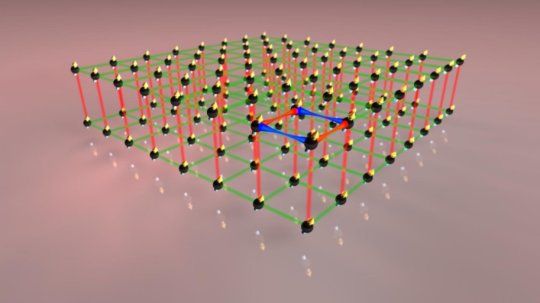

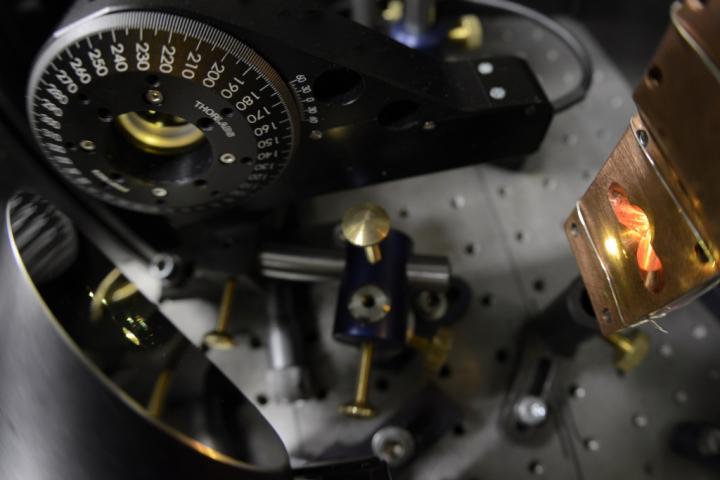

We generally derive our experimental knowledge of quantum phenomena from experiments carried out using sophisticated equipment under exotic conditions: at extremely low temperatures and in a vacuum, isolating quantum objects from the disturbing influence of the environment. Scientists from the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Polish Academy of Sciences (IPC PAS) in Warsaw, led by Prof. Jacek Waluk and Prof. Czeslaw Radzewicz’s group from the Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw (FUW), have just shown that one of the most spectacular quantum phenomena — that of tunneling — takes place even at temperatures above the boiling point of water. However, what is particularly surprising is the fact that the observed effect applies to hydrogen nuclei, which tunnel in particles floating in solution. The results of measurements leave no doubt: in the studied system, in conditions typical for our environment, tunneling turns out to be the main factor responsible for the chemical reaction!

“For some time chemists have been getting used to the idea that electrons in molecules can tunnel. We have shown that in the molecule it is also possible for protons, that is, nuclei of hydrogen atoms, to tunnel. So we have proof that a basic chemical reaction can occur as a result of tunneling, and in addition in solution and at room temperature or higher,” explains Prof. Waluk.

Read more