More insights around the logical quantum gate for photons discovered by Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (MPQ). Being able to leverage this gate enables Qubits in transmission and processing can be more controlled and manipulated through this discovery, and places us closer to a stable Quantum Computing environment.

MPQ scientists take an important step towards a logical quantum gate for photons.

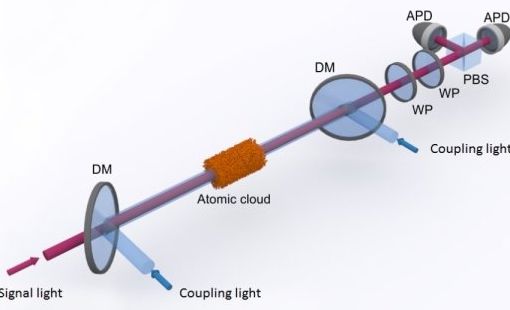

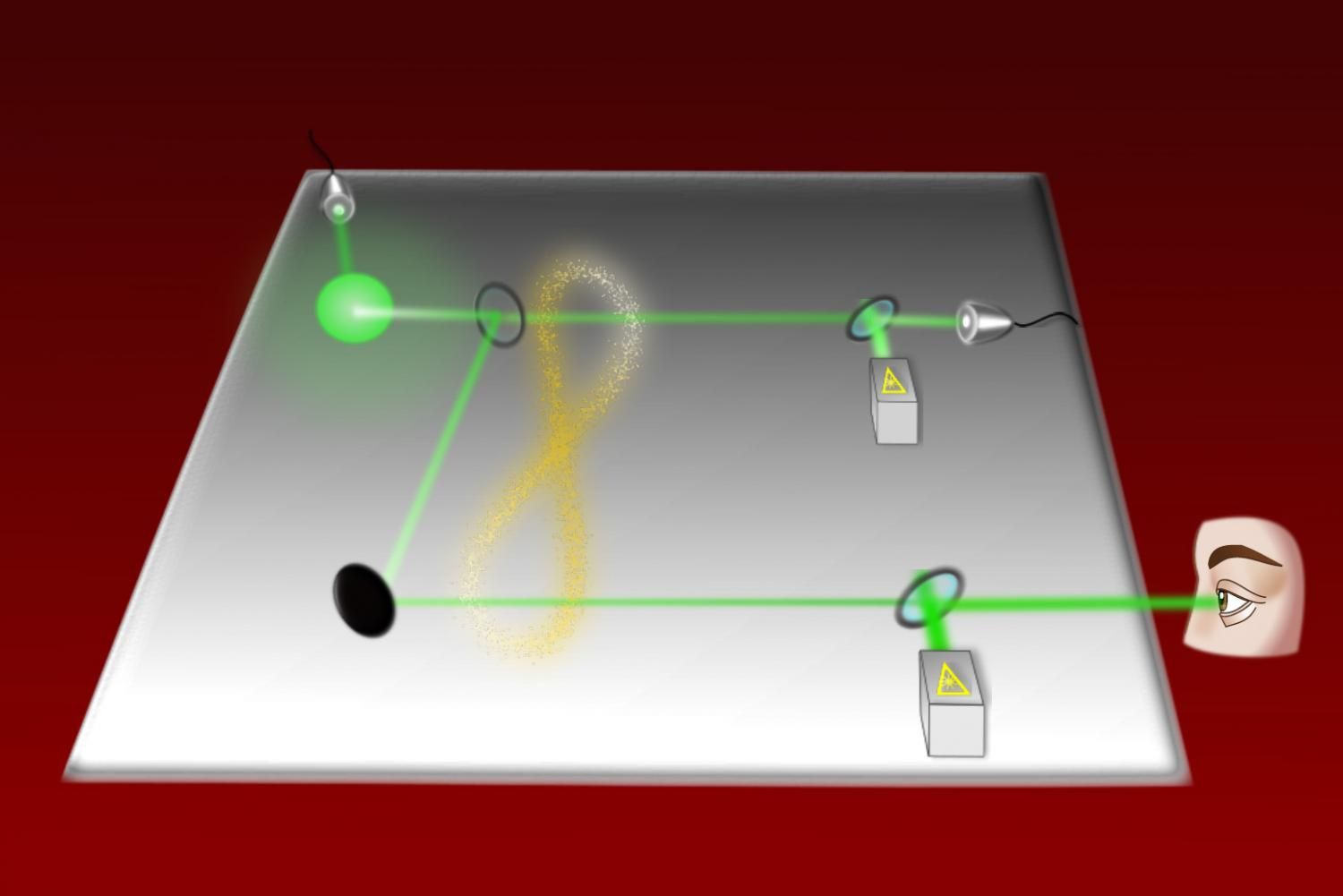

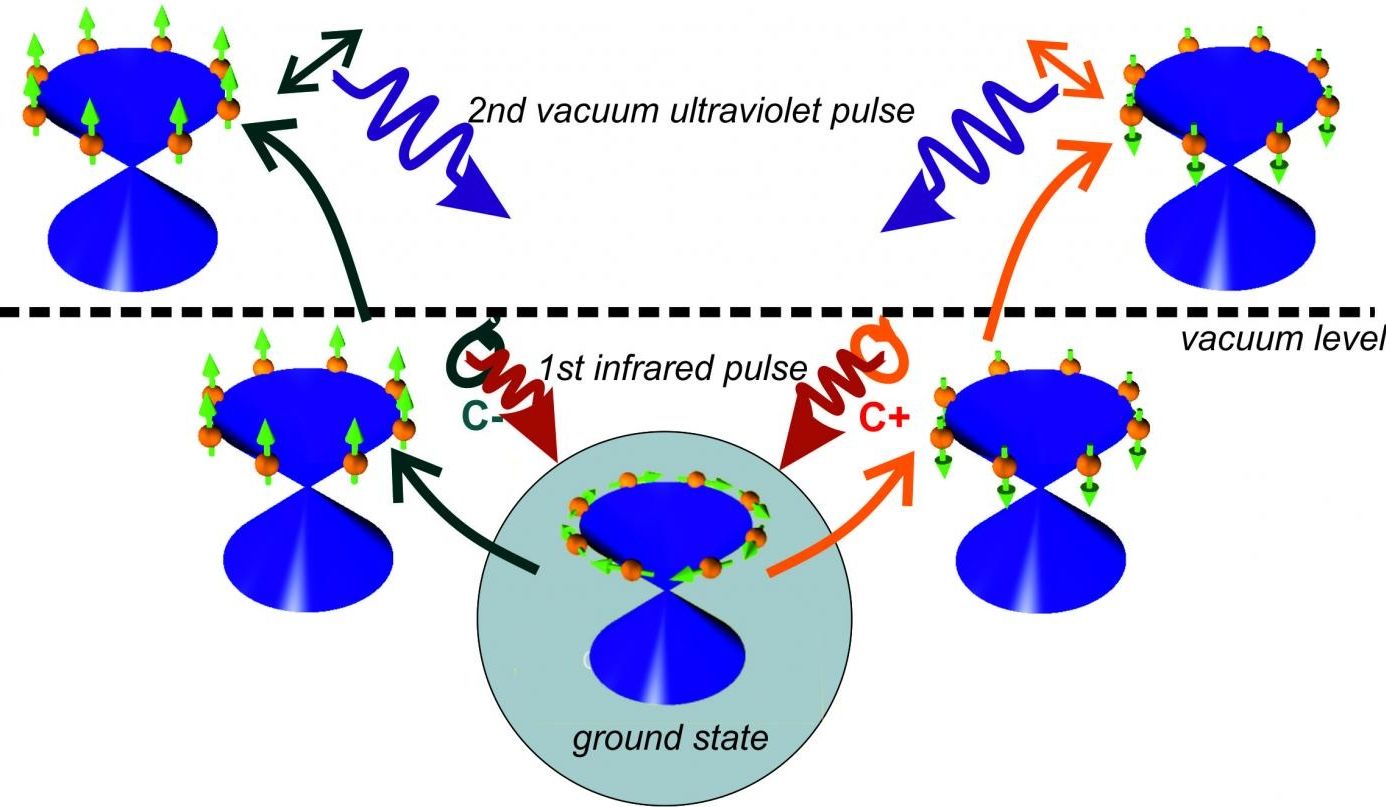

Scientists from all over the world are working on concepts for future quantum computers and their experimental realization. Commonly, a typical quantum computer is considered to be based on a network of quantum particles that serve for storing, encoding and processing quantum information. In analogy to the case of a classical computer a quantum logic gate that assigns output signals to input signals in a deterministic way would be an essential building block. A team around Dr. Stephan Dürr from the Quantum Dynamics Division of Prof. Gerhard Rempe at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics has now demonstrated in an experiment how an important gate operation — the exchange of the binary bit values 0 and 1 — can be realized with single photons. A first light pulse containing one photon only is stored as an excitation in an ultracold cloud of about 100,000 rubidium atoms.